TemboHeart Project for Girls and Women in Tanzania

Donation protected

Please view our 2021 fundraiser — this page will be deleted soon. Thank you!

www.gofundme.com/TemboHeart-project-2021

EMPOWER GIRLS & WOMEN TO REACH THEIR FULL POTENTIAL WITH ACCESS TO SUSTAINABLE MENSTRUAL HEALTH SOLUTIONS

TemboHeart (previously the Endulen Maasai Women’s Health Project) was created in 2015 to provide Maasai girls and women in a remote village in East Africa with an innovative resource: washable, reusable menstrual kits and vital health education. I coordinate the project from California with my Maasai partner and with local producers in Tanzania. In the past five years, we have distributed more than 750 kits and hundreds more through joint partnerships.

Menstrual Hygiene Management means ensuring girls and women live in an environment that values and supports their ability to manage their menstruation with dignity.

Menstrual Hygiene Management means ensuring girls and women live in an environment that values and supports their ability to manage their menstruation with dignity.

2020 GOALS & FUNDING

Since travel is not possible this year, my project partner, Lemali Sabore, will pick up the kits, manage and organize the meetings. As in previous years, I will wire the donated funds to the kit producers based on their production time frame.

• Purchasing 200 kits: $2000

• Meeting materials and presenter stipends (three meetings): $450

• Transportation to pick up and deliver kits (three meetings in different locations): $250

TOTAL: $2700

1st distribution: September 9, 2020

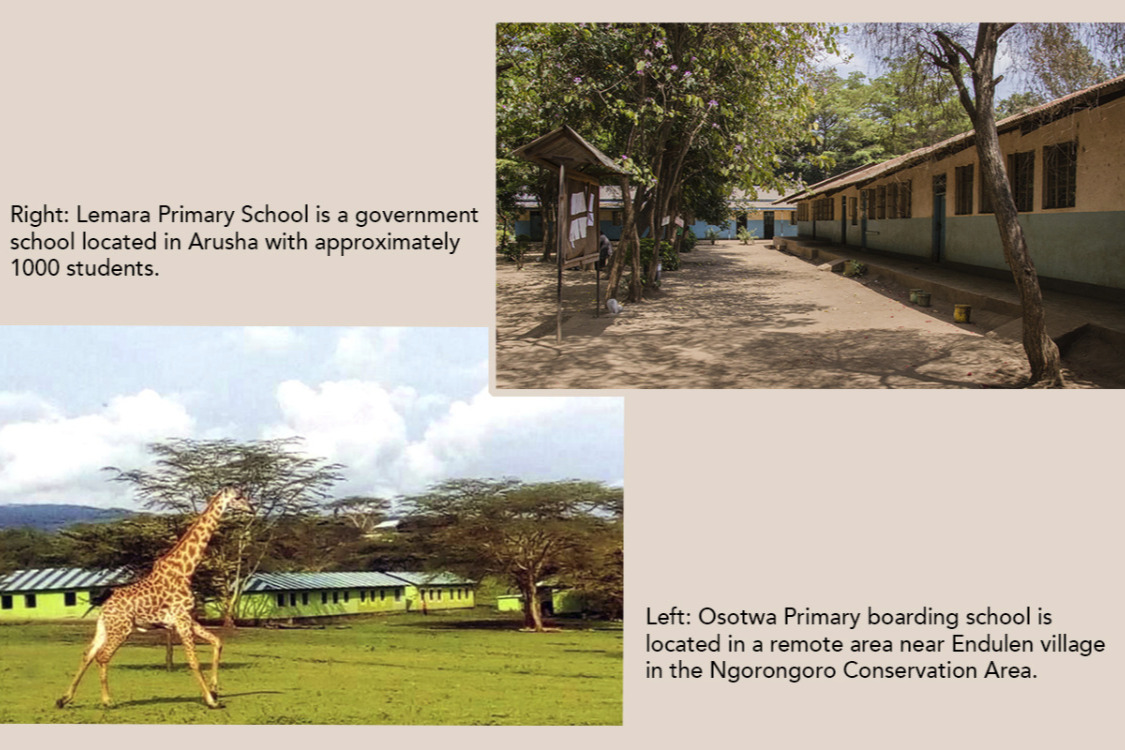

Distribute 50 kits at Osotwa Primary boarding school at Endulen village.

2nd distribution: October 2020

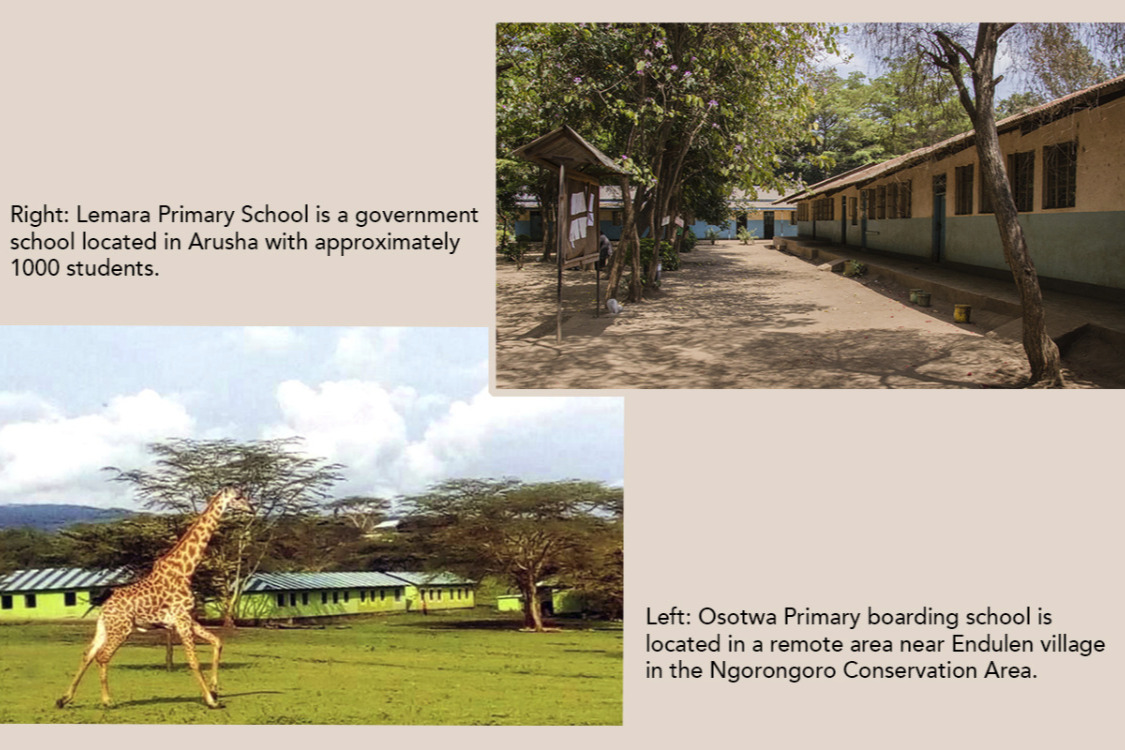

Distribute 50 kits to Lemara Primary School in Arusha located in an low income area.

3rd distribution: November 2020

Distribute 100 kits to Maasai women at Endulen village at a central location (as we have done in previous years).

We provide Maasai girls and women in a remote village in East Africa with an innovative resource: washable, reusable menstrual kits and vital health education.

We provide Maasai girls and women in a remote village in East Africa with an innovative resource: washable, reusable menstrual kits and vital health education.

THE ISSUE

Millions of girls and women around the world stay home from school or work during their periods because they can’t afford sanitary supplies. They resort to using rags, mattress stuffing, banana leaves and newspaper to manage their monthly periods. And with resources this unsanitary and unreliable, staying in school, working at a job or tending to the home and family becomes increasingly difficult and very unhealthy.

Being born female in many cultures automatically equals vulnerability, obstacles and lack of education, resources and support. Additional factors such as poverty, cultural customs and isolation make it extremely difficult for girls to have the right to make their own choices. In traditional Maasai societies where getting married and having children determine a girl’s worth, fewer than one in 100 Maasai girls complete secondary school (high school) and nine out of 10 are married off before age 15.

More than one in 10 first-time mothers in Tanzania are aged 15-19 and in rural areas like Endulen village the numbers are even higher. Girls and women often don’t understand their menstrual cycle, how pregnancy occurs or what happens to their bodies during pregnancy and childbirth.

More than one in 10 first-time mothers in Tanzania are aged 15-19 and in rural areas like Endulen village the numbers are even higher. Girls and women often don’t understand their menstrual cycle, how pregnancy occurs or what happens to their bodies during pregnancy and childbirth.

“Women who start having children in adolescence tend to have more children and shorter spacing between pregnancies – all of which are risk factors for maternal and neonatal mortality. The neonatal mortality rate is highest among mothers under 20 years of age at 45 per 1000 live births compared with 29 per 1000 for mothers aged 20 to 29 years.

Maternal death rates are closely linked with the high fertility rates and low socioeconomic status of women, especially the lack of influence that women have over their own health care or over the daily household budget. About 40 percent of Tanzanian women do not participate in significant decisions regarding their own health care. On average, every Tanzanian woman gives birth to 5 or 6 children and 1 in 3 of them begins childbearing before their 18th birthday.” (1)

According to the Maasai Girls Education Fund, “Maasai girls face many obstacles to get an education and most of those are related to the high level of poverty among the Maasai. The cost of education is prohibitive for most families, and the promise of a dowry is a powerful incentive for arranging a daughter’s marriage as soon as she crosses the childhood bridge.” (2) If families can pay education costs, there is a cultural preference for educating boys first. The Maasai believe that when a girl marries, she becomes a member of her husband’s family and therefore offers no support to her biological family.

About 40 percent of Tanzanian women do not participate in significant decisions regarding their own health care.

About 40 percent of Tanzanian women do not participate in significant decisions regarding their own health care.

After our 2017 kit distribution at a secondary school in Endulen, the Advanced Level Matron, Ms. Irene Mlay, wrote to me that “this school is in a remote place, most girls are from peasant families, especially Maasai, and for them education, especially to girls, is not important. In recent years, we can see them at least responding positively to education after some family members have been educated [through] government efforts, law enforcement and sponsorship from charitable people and organizations. Otherwise girls are very early forced to be married, and they are traditionally raised with that mentality. Girls from families with problems are hardly even able to get their social demands met.”

For girls who can enroll in school, their continued attendance is vulnerable and can easily be derailed — something as simple as lack of sanitary supplies can mean the difference between education and early marriage. In a groundbreaking study from the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London, findings from a two-year trial in rural Uganda showed that providing free sanitary products and education about puberty increased girls’ attendance at school. Researchers believe that the cost of hygiene products and the difficulties in managing periods play a key role in keeping girls out of school.” (3)

For girls who can enroll in school, their continued attendance is vulnerable and can easily be derailed by something as simple as lack of sanitary supplies and can mean the difference between education and early marriage.

For girls who can enroll in school, their continued attendance is vulnerable and can easily be derailed by something as simple as lack of sanitary supplies and can mean the difference between education and early marriage.

Many of the Maasai women at Endulen village have not received any formal education and were married young. Families live in isolated huts without electricity or plumbing and a woman’s daily chores consist of hard physical labor: collecting firewood and water (often miles from home), milking the cows and goats, washing clothes at the river and cooking over an open fire in an unventilated hut. They often struggle to stay healthy and care for their families without a safe, reliable way to manage their periods, and something as simple as reusable sanitary supplies can be life changing. Additionally, the education we provide helps them to better understand their bodies and health issues, which ultimately leads to raising healthier children.

At Endulen village families live in isolated huts without electricity or plumbing and a woman’s daily chores consist of constant physical labor.

At Endulen village families live in isolated huts without electricity or plumbing and a woman’s daily chores consist of constant physical labor.

Studies from UNICEF show that, “investing in girls’ education transforms communities, countries and the entire world. Girls who receive an education are less likely to marry young and more likely to lead healthy, productive lives. They earn higher incomes, participate in the decisions that most affect them and build better futures for themselves and their families. Girls’ education strengthens economies and reduces inequality. It contributes to more stable, resilient societies that give all individuals – including boys and men – the opportunity to fulfill their potential.” (4)

STUDIES ON THE ISSUE

There’s no shortage of online articles both supporting and questioning the idea that access to menstrual supplies keeps girls in school. Attendance data is an important way to measure if the kits are successful but getting accurate information in countries like Tanzania can be difficult. Researchers still lack comprehensive data on many questions, some as basic as knowing the average age of menstruation in sub-Saharan Africa.

In 2018 we partnered with the German NGO Endulen, e.V. and helped distribute 400 menstrual kits to a secondary boarding school at Endulen. The area is extremely remote and any shop to purchase pads, if the girls have money, is more than six miles (10 km) away. The school is unable to provide any supplies. Six months later, doctors from the NGO returned and asked 200 girls to answer a few questions about using the kits. Results included:

• 97% of the girls used the kits since distribution

• 85% liked the quality of the kit materials

• Nearly 40% of the girls used the kits every month

• 38% of girls had at least one sick day and 17% had five sick days during menstruation

• 11% had reduced sick days and felt more comfortable in school

• 27% felt more comfortable and self confident

• 9% said their personal hygiene had improved

In a 2016 NPR story, Nurith Aizenman interviewed Marni Sommer, a professor at Columbia University who was among the first social science researchers to address menstrual hygiene issues in 2004. Sommer explains that the early studies were surveys of girls across Africa who reported “a range of concerns about their periods, including, she says, ‘fear, shame, embarrassment, impact on feelings of confidence.’”

Other crucial factors include “how sensitive teachers at the school are about the menstruation challenge or what the toilets at the school are like. ‘If girls don't have a safe, private place to manage their periods ... then even with supplies or even with education, they still will be hindered,’ says Sommer.”

The article also brings up an important consideration: “Does there have to be some educational or health justification for spending aid dollars to help girls manage their periods? It suggests this isn't worth doing for its own sake.” (5)

Over the past four years, I’ve participated in kit distributions for more than 1500 schoolgirls and women in Tanzania. Gratitude is the overall feeling during the meetings and that the kits will help make life easier — whether attending school or working at a job or raising a family. They provide a solution to one piece of a much larger puzzle. The kits don’t fix the issues of gender inequality, lack of facilities, early marriage or cultural taboos but they do improve life quality and self confidence, which is immeasurable. And the good news at Endulen is that men in leadership roles are becoming more involved in supporting women’s health issues. Last year we met with the area’s chief who supports our project and others like it; the school headmasters are welcoming and provide time and space for the meetings. One headmaster even stayed for the entire two hour meeting and encouraged us to return the following year.

Over the past four years, I’ve participated in kit distributions for more than 1500 schoolgirls and women in Tanzania

Over the past four years, I’ve participated in kit distributions for more than 1500 schoolgirls and women in Tanzania

EDUCATIONAL MATERIALS

One of my initial attractions to the Days for Girls kits was the emphasis the organization places on education and how it is an essential component to the kit distributions. Through communications for our project, I’ve learned from school headmasters, teachers, students and Maasai women that female hygiene and menstruation education are not part of school curriculum in Tanzania. Girls begin menstruating and don’t know what’s happening; women don’t understand how pregnancy occurs or what to do about health issues and infections.

For our meetings, we use the Days for Girls curriculum to provide information on a variety of topics including the menstrual cycle, personal hygiene, infections and diseases, pregnancy, HIV, self defense, female and male anatomy and how to care for and use the kits.

For this educational portion at Endulen, we rely on the help of Dr. Mameso Frederick from the Endulen hospital. As a Maasai woman and a doctor, she provides a unique perspective on the cultural and educational issues girls and women face living in a remote village. In Arusha, we will train one of the teachers to present information to the students. If English is spoken, I also can lead the educational section and Lemali is confident talking to any sized group anywhere.

We provide Dr. Mameso Frederick from Endulen Hospital with Days for Girls' educational resource materials and curriculum for our meetings.

We provide Dr. Mameso Frederick from Endulen Hospital with Days for Girls' educational resource materials and curriculum for our meetings.

THE REUSABLE KITS

The kits we purchase in Tanzania are created locally using the Days for Girls enterprise guidelines and training. Days for Girls, a U.S. nonprofit, was founded in 2008 by Celeste Mergens when she was working in Kenya. The reusable kit is now in its 28th iteration, informed by extensive feedback and designed to meet unique cultural and environmental conditions in communities throughout the world.

The kits are contained in a colorful fabric drawstring bag to hold all components: two waterproof shields, eight absorbent liners, two pairs of panties, two plastic bags for washing and storage, a washcloth and bar of soap. The absorbent liner pads are sewn from brightly colored cloth to camouflage staining and unfold to look like a washcloth so they can dry outside in the sun without causing embarrassment. The shields contain a waterproof liner that easily snaps into place. Studies show that the kits last up to three years, are comfortable and work well in a variety of settings.

“I really like the kits. It’s very awesome and beautiful, it’s very amazing in my heart. I’m very thankful because this is the help that a person should give to another person. So please please keep continuing giving us the help because you know at school here they are some hard things to get but with this it’s very, very good for us. So thank you very much, continue being kind and lovely. I love you guys.”

“I really like the kits. It’s very awesome and beautiful, it’s very amazing in my heart. I’m very thankful because this is the help that a person should give to another person. So please please keep continuing giving us the help because you know at school here they are some hard things to get but with this it’s very, very good for us. So thank you very much, continue being kind and lovely. I love you guys.”

“I’m proud for you to be here. The education we get and the knowledge we also try to apply outside from here. We all thank you for the materials that you brought for us, I mean the towel pads, because the industrial pads they are not fine on our environment. By giving us the towel pads, we can see that you can reuse them and help our environment. We all thank you.”

“I’m proud for you to be here. The education we get and the knowledge we also try to apply outside from here. We all thank you for the materials that you brought for us, I mean the towel pads, because the industrial pads they are not fine on our environment. By giving us the towel pads, we can see that you can reuse them and help our environment. We all thank you.”

— Secondary school students after receiving their kits

Studies show that the kits last up to three years, are comfortable and work well in a variety of settings.

Studies show that the kits last up to three years, are comfortable and work well in a variety of settings.

CREATING TEMBOHEART

I first learned about the struggles girls and women in developing countries endure while I was sitting in the shade of a huge tree at a remote Maasai village in Tanzania called Endulen. It was 2015, and I was surrounded by a dozen women wrapped in brightly colored cloths and decorated with beautiful beaded jewelry. Goats grazed nearby and babies fussed as the women explained their situation: they had no source of sanitary supplies and would resort to using rags or old newspaper to manage their periods. This made taking care of their families or working at a job very difficult and uncomfortable. My friend Lemali Sabore, a unique Maasai man I met in 2012, translated to English for me. Could I help, the women asked?

Once home, I began researching and learned about this worldwide issue affecting girls and women especially in developing countries like Tanzania. Without Menstrual Hygiene Management (MHM) and access to sanitary supplies, girls drop out of school, marry young and perpetuate the gender inequality that already touches all aspects of their lives. And for Maasai girls in East Africa, extreme poverty and discriminating cultural beliefs often create an unsolvable obstacle to getting an education.

My efforts led to learning about a reusable menstrual kit that would last up to three years with pads that required little water to clean and could be disinfected drying in the sun. My project partner talked to the women, and they were very interested in trying the kits. In addition to making kits in the U.S., the Days for Girls international branch teaches people in other countries how to produce and sell the kits locally. We have purchased kits from small businesses in both Kenya and Tanzania over the years.

In traditional Maasai villages, fewer than one in 100 Maasai girls complete secondary school (high school) and nine out of 10 are married off by their parents before age 15.

In traditional Maasai villages, fewer than one in 100 Maasai girls complete secondary school (high school) and nine out of 10 are married off by their parents before age 15.

I began a crowdfunding campaign and we held our first meeting in 2016 at the Endulen hospital. I have continued my education by becoming a Days for Girls Ambassador and attending a day-long instructional workshop with founder Celeste Mergens. Through social media, I have encouraged others to learn about the issue and provided information about the kits. A two-year partnership with a German NGO helped distribute nearly 1000 additional kits at Endulen. Now, the menstrual hygiene issue is more mainstream, and publicity such as Period. End of Sentence winning an Oscar in 2018 helped people learn about the shame, discrimination and taboos that accompany girls and women when they menstruate.

My project partner, Lemali Sabore, is comfortable in any setting teaching women about the kits. His insights and resources are essential to the success of TemboHeart.

My project partner, Lemali Sabore, is comfortable in any setting teaching women about the kits. His insights and resources are essential to the success of TemboHeart.

My initial focus was for Maasai women, 20-40 years old, most of whom had never attended school and lived traditional village lives. By our second year, I had learned more about the connection between girls staying in school and having adequate menstrual supplies so we included an Endulen secondary school for kit distribution. Last year, attending a partner’s distribution at a remote Maasai primary school showed me how crucial education and resources are for girls just before they start menstruating.

The education we provide Maasai women helps them to better understand their bodies and health issues which leads to raising healthier children.

The education we provide Maasai women helps them to better understand their bodies and health issues which leads to raising healthier children.

For me personally, learning about this issue was enough to inspire me to do something, and the reports and statistics reinforce how great the need is to educate women and ensure good menstrual health worldwide. But my greatest joy is being in a room with 200 school girls in uniform or out in the savannah with 100 Maasai women wrapped in colorful fabrics and giving them kits. Their fascination and attention as they learn about their bodies and the joy they show when they receive a kit is a truly amazing experience for me. That happiness transcends language, culture, age and experience and those smiles are so beautiful.

My experiences in Tanzania have been fascinating and include some of my happiest moments ever. (Top photo by Embarway Secondary School student | Bottom photo by Patricia Neugebauer)

My experiences in Tanzania have been fascinating and include some of my happiest moments ever. (Top photo by Embarway Secondary School student | Bottom photo by Patricia Neugebauer)

LOCATIONS IN TANZANIA

Endulen

Endulen is one of several Maasai villages in the Ngorongoro Conservation Area, a UNESCO World Heritage site in northern Tanzania that covers more than 8,292 square kilometers (5,152 miles). According to UNESCO, the area includes “vast expanses of highland plains, savanna, savanna woodlands and forests. Established in 1959 as a multiple land use area, with wildlife coexisting with semi-nomadic Maasai pastoralists practicing traditional livestock grazing, it includes the spectacular Ngorongoro Crater, the world’s largest caldera. The property has global importance for biodiversity conservation due to the presence of globally threatened species, the density of wildlife inhabiting the area and the annual migration of wildebeest, zebra, gazelles and other animals into the northern plains. Extensive archaeological research has also yielded a long sequence of evidence of human evolution and human-environment dynamics, including early hominid footprints dating back 3.6 million years.” (6)

Endulen, a remote Maasai village in northern Tanzania, is as beautiful as it is isolated.

Endulen, a remote Maasai village in northern Tanzania, is as beautiful as it is isolated.

The town at Endulen is where food and supplies can be purchased and is also a friendly gathering spot.

The town at Endulen is where food and supplies can be purchased and is also a friendly gathering spot.

On the road to Endulen, it's common to see the young herder boys with livestock but you never know who will be hanging around!

On the road to Endulen, it's common to see the young herder boys with livestock but you never know who will be hanging around!

Lemali at home with some of his livestock and a boy he hires to take care of the sheep and goats.

Lemali at home with some of his livestock and a boy he hires to take care of the sheep and goats.

Arusha

Arusha is a city in Tanzania located at the base of Mount Meru and a gateway to safari destinations and to Africa's highest peak, Mount Kilimanjaro which is 100 kilometers northeast. Tourism is a major part of Arusha’s economy as the city is located near some of the greatest national parks and game reserves in Africa including Serengeti National Park, Kilimanjaro National Park, Ngorongoro Conservation Area, Arusha National Park, Lake Manyara National Park, and Tarangire National Park. (7)

Women often open small produce stands to make a little money each day for food and supplies.

Women often open small produce stands to make a little money each day for food and supplies.

Arusha is a bustling city filled with markets, street vendors, workers — there's always something going on day or night.

Arusha is a bustling city filled with markets, street vendors, workers — there's always something going on day or night.

RESOURCES

Days for Girls

daysforgirls.org

Days for Girls increases access to menstrual care and education by developing global partnerships, cultivating social enterprises, mobilizing volunteers, and innovating sustainable solutions that shatter stigmas and limitations for women and girls.

Moskito Handmade

https://moskitohandmade.com/

An artisanal boutique shop in Northern Tanzania producing Days for Girls and Moskito reusable kits and featuring unique handmade items.

Tembo is the Swahili word for elephant and these intelligent, family-oriented mammals are literally bighearted — the average elephant heart weights 26-46 pounds (12-21 kg). I admire the elephant’s matriarchal society and the way they care for each other. For me, TemboHeart means taking care of our world community and each other, however close or far away. When you support projects that create positive social change in the world, your bigheartedness can directly impact the direction of someone’s life.

View my Africa images portfolio on Instagram at https://www.instagram.com/lynnmarlowe/

NOTES

1. Department of Global Health and Population, The Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, 2015

Women’s Health in Tanzania

https://projects.iq.harvard.edu/ppiud/womens-health-tanzania

2. Maasai Girls Education Fund

http://maasaigirlseducation.org/

3. School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London

"Keeping African Girls in School with Better Sanitary Care," 2018

https://www.afripads.com/groundbreaking-study-on-menstruation-and-girls-school-attendance/

4. UNICEF

Girls’ Education: Gender equality in education benefits every child

https://www.unicef.org/education/girls-education

5. NPR Goats and Soda: “Does Handing Out Sanitary Pads Really Get Girls To Stay In School?” by Nurith Aizenman

https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2016/12/28/506472549/does-handing-out-sanitary-pads-really-get-girls-to-stay-in-school

6. UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) which seeks to build peace through international cooperation in education, the sciences and culture.

https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/39

7. Wikipedia: Arusha

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arusha

Accessed online May 5, 2020

All photos are mine except where noted.

Copyright @ Lynn Marlowe

www.gofundme.com/TemboHeart-project-2021

EMPOWER GIRLS & WOMEN TO REACH THEIR FULL POTENTIAL WITH ACCESS TO SUSTAINABLE MENSTRUAL HEALTH SOLUTIONS

TemboHeart (previously the Endulen Maasai Women’s Health Project) was created in 2015 to provide Maasai girls and women in a remote village in East Africa with an innovative resource: washable, reusable menstrual kits and vital health education. I coordinate the project from California with my Maasai partner and with local producers in Tanzania. In the past five years, we have distributed more than 750 kits and hundreds more through joint partnerships.

Menstrual Hygiene Management means ensuring girls and women live in an environment that values and supports their ability to manage their menstruation with dignity.

Menstrual Hygiene Management means ensuring girls and women live in an environment that values and supports their ability to manage their menstruation with dignity.2020 GOALS & FUNDING

Since travel is not possible this year, my project partner, Lemali Sabore, will pick up the kits, manage and organize the meetings. As in previous years, I will wire the donated funds to the kit producers based on their production time frame.

• Purchasing 200 kits: $2000

• Meeting materials and presenter stipends (three meetings): $450

• Transportation to pick up and deliver kits (three meetings in different locations): $250

TOTAL: $2700

1st distribution: September 9, 2020

Distribute 50 kits at Osotwa Primary boarding school at Endulen village.

2nd distribution: October 2020

Distribute 50 kits to Lemara Primary School in Arusha located in an low income area.

3rd distribution: November 2020

Distribute 100 kits to Maasai women at Endulen village at a central location (as we have done in previous years).

We provide Maasai girls and women in a remote village in East Africa with an innovative resource: washable, reusable menstrual kits and vital health education.

We provide Maasai girls and women in a remote village in East Africa with an innovative resource: washable, reusable menstrual kits and vital health education.THE ISSUE

Millions of girls and women around the world stay home from school or work during their periods because they can’t afford sanitary supplies. They resort to using rags, mattress stuffing, banana leaves and newspaper to manage their monthly periods. And with resources this unsanitary and unreliable, staying in school, working at a job or tending to the home and family becomes increasingly difficult and very unhealthy.

Being born female in many cultures automatically equals vulnerability, obstacles and lack of education, resources and support. Additional factors such as poverty, cultural customs and isolation make it extremely difficult for girls to have the right to make their own choices. In traditional Maasai societies where getting married and having children determine a girl’s worth, fewer than one in 100 Maasai girls complete secondary school (high school) and nine out of 10 are married off before age 15.

More than one in 10 first-time mothers in Tanzania are aged 15-19 and in rural areas like Endulen village the numbers are even higher. Girls and women often don’t understand their menstrual cycle, how pregnancy occurs or what happens to their bodies during pregnancy and childbirth.

More than one in 10 first-time mothers in Tanzania are aged 15-19 and in rural areas like Endulen village the numbers are even higher. Girls and women often don’t understand their menstrual cycle, how pregnancy occurs or what happens to their bodies during pregnancy and childbirth.“Women who start having children in adolescence tend to have more children and shorter spacing between pregnancies – all of which are risk factors for maternal and neonatal mortality. The neonatal mortality rate is highest among mothers under 20 years of age at 45 per 1000 live births compared with 29 per 1000 for mothers aged 20 to 29 years.

Maternal death rates are closely linked with the high fertility rates and low socioeconomic status of women, especially the lack of influence that women have over their own health care or over the daily household budget. About 40 percent of Tanzanian women do not participate in significant decisions regarding their own health care. On average, every Tanzanian woman gives birth to 5 or 6 children and 1 in 3 of them begins childbearing before their 18th birthday.” (1)

According to the Maasai Girls Education Fund, “Maasai girls face many obstacles to get an education and most of those are related to the high level of poverty among the Maasai. The cost of education is prohibitive for most families, and the promise of a dowry is a powerful incentive for arranging a daughter’s marriage as soon as she crosses the childhood bridge.” (2) If families can pay education costs, there is a cultural preference for educating boys first. The Maasai believe that when a girl marries, she becomes a member of her husband’s family and therefore offers no support to her biological family.

About 40 percent of Tanzanian women do not participate in significant decisions regarding their own health care.

About 40 percent of Tanzanian women do not participate in significant decisions regarding their own health care. After our 2017 kit distribution at a secondary school in Endulen, the Advanced Level Matron, Ms. Irene Mlay, wrote to me that “this school is in a remote place, most girls are from peasant families, especially Maasai, and for them education, especially to girls, is not important. In recent years, we can see them at least responding positively to education after some family members have been educated [through] government efforts, law enforcement and sponsorship from charitable people and organizations. Otherwise girls are very early forced to be married, and they are traditionally raised with that mentality. Girls from families with problems are hardly even able to get their social demands met.”

For girls who can enroll in school, their continued attendance is vulnerable and can easily be derailed — something as simple as lack of sanitary supplies can mean the difference between education and early marriage. In a groundbreaking study from the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London, findings from a two-year trial in rural Uganda showed that providing free sanitary products and education about puberty increased girls’ attendance at school. Researchers believe that the cost of hygiene products and the difficulties in managing periods play a key role in keeping girls out of school.” (3)

For girls who can enroll in school, their continued attendance is vulnerable and can easily be derailed by something as simple as lack of sanitary supplies and can mean the difference between education and early marriage.

For girls who can enroll in school, their continued attendance is vulnerable and can easily be derailed by something as simple as lack of sanitary supplies and can mean the difference between education and early marriage. Many of the Maasai women at Endulen village have not received any formal education and were married young. Families live in isolated huts without electricity or plumbing and a woman’s daily chores consist of hard physical labor: collecting firewood and water (often miles from home), milking the cows and goats, washing clothes at the river and cooking over an open fire in an unventilated hut. They often struggle to stay healthy and care for their families without a safe, reliable way to manage their periods, and something as simple as reusable sanitary supplies can be life changing. Additionally, the education we provide helps them to better understand their bodies and health issues, which ultimately leads to raising healthier children.

At Endulen village families live in isolated huts without electricity or plumbing and a woman’s daily chores consist of constant physical labor.

At Endulen village families live in isolated huts without electricity or plumbing and a woman’s daily chores consist of constant physical labor.Studies from UNICEF show that, “investing in girls’ education transforms communities, countries and the entire world. Girls who receive an education are less likely to marry young and more likely to lead healthy, productive lives. They earn higher incomes, participate in the decisions that most affect them and build better futures for themselves and their families. Girls’ education strengthens economies and reduces inequality. It contributes to more stable, resilient societies that give all individuals – including boys and men – the opportunity to fulfill their potential.” (4)

STUDIES ON THE ISSUE

There’s no shortage of online articles both supporting and questioning the idea that access to menstrual supplies keeps girls in school. Attendance data is an important way to measure if the kits are successful but getting accurate information in countries like Tanzania can be difficult. Researchers still lack comprehensive data on many questions, some as basic as knowing the average age of menstruation in sub-Saharan Africa.

In 2018 we partnered with the German NGO Endulen, e.V. and helped distribute 400 menstrual kits to a secondary boarding school at Endulen. The area is extremely remote and any shop to purchase pads, if the girls have money, is more than six miles (10 km) away. The school is unable to provide any supplies. Six months later, doctors from the NGO returned and asked 200 girls to answer a few questions about using the kits. Results included:

• 97% of the girls used the kits since distribution

• 85% liked the quality of the kit materials

• Nearly 40% of the girls used the kits every month

• 38% of girls had at least one sick day and 17% had five sick days during menstruation

• 11% had reduced sick days and felt more comfortable in school

• 27% felt more comfortable and self confident

• 9% said their personal hygiene had improved

In a 2016 NPR story, Nurith Aizenman interviewed Marni Sommer, a professor at Columbia University who was among the first social science researchers to address menstrual hygiene issues in 2004. Sommer explains that the early studies were surveys of girls across Africa who reported “a range of concerns about their periods, including, she says, ‘fear, shame, embarrassment, impact on feelings of confidence.’”

Other crucial factors include “how sensitive teachers at the school are about the menstruation challenge or what the toilets at the school are like. ‘If girls don't have a safe, private place to manage their periods ... then even with supplies or even with education, they still will be hindered,’ says Sommer.”

The article also brings up an important consideration: “Does there have to be some educational or health justification for spending aid dollars to help girls manage their periods? It suggests this isn't worth doing for its own sake.” (5)

Over the past four years, I’ve participated in kit distributions for more than 1500 schoolgirls and women in Tanzania. Gratitude is the overall feeling during the meetings and that the kits will help make life easier — whether attending school or working at a job or raising a family. They provide a solution to one piece of a much larger puzzle. The kits don’t fix the issues of gender inequality, lack of facilities, early marriage or cultural taboos but they do improve life quality and self confidence, which is immeasurable. And the good news at Endulen is that men in leadership roles are becoming more involved in supporting women’s health issues. Last year we met with the area’s chief who supports our project and others like it; the school headmasters are welcoming and provide time and space for the meetings. One headmaster even stayed for the entire two hour meeting and encouraged us to return the following year.

Over the past four years, I’ve participated in kit distributions for more than 1500 schoolgirls and women in Tanzania

Over the past four years, I’ve participated in kit distributions for more than 1500 schoolgirls and women in TanzaniaEDUCATIONAL MATERIALS

One of my initial attractions to the Days for Girls kits was the emphasis the organization places on education and how it is an essential component to the kit distributions. Through communications for our project, I’ve learned from school headmasters, teachers, students and Maasai women that female hygiene and menstruation education are not part of school curriculum in Tanzania. Girls begin menstruating and don’t know what’s happening; women don’t understand how pregnancy occurs or what to do about health issues and infections.

For our meetings, we use the Days for Girls curriculum to provide information on a variety of topics including the menstrual cycle, personal hygiene, infections and diseases, pregnancy, HIV, self defense, female and male anatomy and how to care for and use the kits.

For this educational portion at Endulen, we rely on the help of Dr. Mameso Frederick from the Endulen hospital. As a Maasai woman and a doctor, she provides a unique perspective on the cultural and educational issues girls and women face living in a remote village. In Arusha, we will train one of the teachers to present information to the students. If English is spoken, I also can lead the educational section and Lemali is confident talking to any sized group anywhere.

We provide Dr. Mameso Frederick from Endulen Hospital with Days for Girls' educational resource materials and curriculum for our meetings.

We provide Dr. Mameso Frederick from Endulen Hospital with Days for Girls' educational resource materials and curriculum for our meetings.THE REUSABLE KITS

The kits we purchase in Tanzania are created locally using the Days for Girls enterprise guidelines and training. Days for Girls, a U.S. nonprofit, was founded in 2008 by Celeste Mergens when she was working in Kenya. The reusable kit is now in its 28th iteration, informed by extensive feedback and designed to meet unique cultural and environmental conditions in communities throughout the world.

The kits are contained in a colorful fabric drawstring bag to hold all components: two waterproof shields, eight absorbent liners, two pairs of panties, two plastic bags for washing and storage, a washcloth and bar of soap. The absorbent liner pads are sewn from brightly colored cloth to camouflage staining and unfold to look like a washcloth so they can dry outside in the sun without causing embarrassment. The shields contain a waterproof liner that easily snaps into place. Studies show that the kits last up to three years, are comfortable and work well in a variety of settings.

“I really like the kits. It’s very awesome and beautiful, it’s very amazing in my heart. I’m very thankful because this is the help that a person should give to another person. So please please keep continuing giving us the help because you know at school here they are some hard things to get but with this it’s very, very good for us. So thank you very much, continue being kind and lovely. I love you guys.”

“I really like the kits. It’s very awesome and beautiful, it’s very amazing in my heart. I’m very thankful because this is the help that a person should give to another person. So please please keep continuing giving us the help because you know at school here they are some hard things to get but with this it’s very, very good for us. So thank you very much, continue being kind and lovely. I love you guys.” “I’m proud for you to be here. The education we get and the knowledge we also try to apply outside from here. We all thank you for the materials that you brought for us, I mean the towel pads, because the industrial pads they are not fine on our environment. By giving us the towel pads, we can see that you can reuse them and help our environment. We all thank you.”

“I’m proud for you to be here. The education we get and the knowledge we also try to apply outside from here. We all thank you for the materials that you brought for us, I mean the towel pads, because the industrial pads they are not fine on our environment. By giving us the towel pads, we can see that you can reuse them and help our environment. We all thank you.” — Secondary school students after receiving their kits

Studies show that the kits last up to three years, are comfortable and work well in a variety of settings.

Studies show that the kits last up to three years, are comfortable and work well in a variety of settings.CREATING TEMBOHEART

I first learned about the struggles girls and women in developing countries endure while I was sitting in the shade of a huge tree at a remote Maasai village in Tanzania called Endulen. It was 2015, and I was surrounded by a dozen women wrapped in brightly colored cloths and decorated with beautiful beaded jewelry. Goats grazed nearby and babies fussed as the women explained their situation: they had no source of sanitary supplies and would resort to using rags or old newspaper to manage their periods. This made taking care of their families or working at a job very difficult and uncomfortable. My friend Lemali Sabore, a unique Maasai man I met in 2012, translated to English for me. Could I help, the women asked?

Once home, I began researching and learned about this worldwide issue affecting girls and women especially in developing countries like Tanzania. Without Menstrual Hygiene Management (MHM) and access to sanitary supplies, girls drop out of school, marry young and perpetuate the gender inequality that already touches all aspects of their lives. And for Maasai girls in East Africa, extreme poverty and discriminating cultural beliefs often create an unsolvable obstacle to getting an education.

My efforts led to learning about a reusable menstrual kit that would last up to three years with pads that required little water to clean and could be disinfected drying in the sun. My project partner talked to the women, and they were very interested in trying the kits. In addition to making kits in the U.S., the Days for Girls international branch teaches people in other countries how to produce and sell the kits locally. We have purchased kits from small businesses in both Kenya and Tanzania over the years.

In traditional Maasai villages, fewer than one in 100 Maasai girls complete secondary school (high school) and nine out of 10 are married off by their parents before age 15.

In traditional Maasai villages, fewer than one in 100 Maasai girls complete secondary school (high school) and nine out of 10 are married off by their parents before age 15.I began a crowdfunding campaign and we held our first meeting in 2016 at the Endulen hospital. I have continued my education by becoming a Days for Girls Ambassador and attending a day-long instructional workshop with founder Celeste Mergens. Through social media, I have encouraged others to learn about the issue and provided information about the kits. A two-year partnership with a German NGO helped distribute nearly 1000 additional kits at Endulen. Now, the menstrual hygiene issue is more mainstream, and publicity such as Period. End of Sentence winning an Oscar in 2018 helped people learn about the shame, discrimination and taboos that accompany girls and women when they menstruate.

My project partner, Lemali Sabore, is comfortable in any setting teaching women about the kits. His insights and resources are essential to the success of TemboHeart.

My project partner, Lemali Sabore, is comfortable in any setting teaching women about the kits. His insights and resources are essential to the success of TemboHeart. My initial focus was for Maasai women, 20-40 years old, most of whom had never attended school and lived traditional village lives. By our second year, I had learned more about the connection between girls staying in school and having adequate menstrual supplies so we included an Endulen secondary school for kit distribution. Last year, attending a partner’s distribution at a remote Maasai primary school showed me how crucial education and resources are for girls just before they start menstruating.

The education we provide Maasai women helps them to better understand their bodies and health issues which leads to raising healthier children.

The education we provide Maasai women helps them to better understand their bodies and health issues which leads to raising healthier children.For me personally, learning about this issue was enough to inspire me to do something, and the reports and statistics reinforce how great the need is to educate women and ensure good menstrual health worldwide. But my greatest joy is being in a room with 200 school girls in uniform or out in the savannah with 100 Maasai women wrapped in colorful fabrics and giving them kits. Their fascination and attention as they learn about their bodies and the joy they show when they receive a kit is a truly amazing experience for me. That happiness transcends language, culture, age and experience and those smiles are so beautiful.

My experiences in Tanzania have been fascinating and include some of my happiest moments ever. (Top photo by Embarway Secondary School student | Bottom photo by Patricia Neugebauer)

My experiences in Tanzania have been fascinating and include some of my happiest moments ever. (Top photo by Embarway Secondary School student | Bottom photo by Patricia Neugebauer)LOCATIONS IN TANZANIA

Endulen

Endulen is one of several Maasai villages in the Ngorongoro Conservation Area, a UNESCO World Heritage site in northern Tanzania that covers more than 8,292 square kilometers (5,152 miles). According to UNESCO, the area includes “vast expanses of highland plains, savanna, savanna woodlands and forests. Established in 1959 as a multiple land use area, with wildlife coexisting with semi-nomadic Maasai pastoralists practicing traditional livestock grazing, it includes the spectacular Ngorongoro Crater, the world’s largest caldera. The property has global importance for biodiversity conservation due to the presence of globally threatened species, the density of wildlife inhabiting the area and the annual migration of wildebeest, zebra, gazelles and other animals into the northern plains. Extensive archaeological research has also yielded a long sequence of evidence of human evolution and human-environment dynamics, including early hominid footprints dating back 3.6 million years.” (6)

Endulen, a remote Maasai village in northern Tanzania, is as beautiful as it is isolated.

Endulen, a remote Maasai village in northern Tanzania, is as beautiful as it is isolated. The town at Endulen is where food and supplies can be purchased and is also a friendly gathering spot.

The town at Endulen is where food and supplies can be purchased and is also a friendly gathering spot. On the road to Endulen, it's common to see the young herder boys with livestock but you never know who will be hanging around!

On the road to Endulen, it's common to see the young herder boys with livestock but you never know who will be hanging around! Lemali at home with some of his livestock and a boy he hires to take care of the sheep and goats.

Lemali at home with some of his livestock and a boy he hires to take care of the sheep and goats.Arusha

Arusha is a city in Tanzania located at the base of Mount Meru and a gateway to safari destinations and to Africa's highest peak, Mount Kilimanjaro which is 100 kilometers northeast. Tourism is a major part of Arusha’s economy as the city is located near some of the greatest national parks and game reserves in Africa including Serengeti National Park, Kilimanjaro National Park, Ngorongoro Conservation Area, Arusha National Park, Lake Manyara National Park, and Tarangire National Park. (7)

Women often open small produce stands to make a little money each day for food and supplies.

Women often open small produce stands to make a little money each day for food and supplies. Arusha is a bustling city filled with markets, street vendors, workers — there's always something going on day or night.

Arusha is a bustling city filled with markets, street vendors, workers — there's always something going on day or night.RESOURCES

Days for Girls

daysforgirls.org

Days for Girls increases access to menstrual care and education by developing global partnerships, cultivating social enterprises, mobilizing volunteers, and innovating sustainable solutions that shatter stigmas and limitations for women and girls.

Moskito Handmade

https://moskitohandmade.com/

An artisanal boutique shop in Northern Tanzania producing Days for Girls and Moskito reusable kits and featuring unique handmade items.

Tembo is the Swahili word for elephant and these intelligent, family-oriented mammals are literally bighearted — the average elephant heart weights 26-46 pounds (12-21 kg). I admire the elephant’s matriarchal society and the way they care for each other. For me, TemboHeart means taking care of our world community and each other, however close or far away. When you support projects that create positive social change in the world, your bigheartedness can directly impact the direction of someone’s life.

View my Africa images portfolio on Instagram at https://www.instagram.com/lynnmarlowe/

NOTES

1. Department of Global Health and Population, The Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, 2015

Women’s Health in Tanzania

https://projects.iq.harvard.edu/ppiud/womens-health-tanzania

2. Maasai Girls Education Fund

http://maasaigirlseducation.org/

3. School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London

"Keeping African Girls in School with Better Sanitary Care," 2018

https://www.afripads.com/groundbreaking-study-on-menstruation-and-girls-school-attendance/

4. UNICEF

Girls’ Education: Gender equality in education benefits every child

https://www.unicef.org/education/girls-education

5. NPR Goats and Soda: “Does Handing Out Sanitary Pads Really Get Girls To Stay In School?” by Nurith Aizenman

https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2016/12/28/506472549/does-handing-out-sanitary-pads-really-get-girls-to-stay-in-school

6. UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) which seeks to build peace through international cooperation in education, the sciences and culture.

https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/39

7. Wikipedia: Arusha

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arusha

Accessed online May 5, 2020

All photos are mine except where noted.

Copyright @ Lynn Marlowe

Organizer

Lynn Marlowe

Organizer

Sacramento, CA