The Ubykh Dictionary Project

Donation protected

My name’s Dr Rhona Fenwick. I’m an archaeologist and linguist who’s spent sixteen years working to document and begin reviving the beautiful, rich, and dying language of the Ubykh people, and I’m humbly asking for your assistance to support me financially while I finish writing the first truly comprehensive Ubykh dictionary.

In the aftermath of the great Caucasian War against Imperial Russia, in May 1864 the Ubykh people were expelled from their native lands on the Black Sea coast around the 2014 Winter Olympic city of Sochi, spelling the beginning of the end for a proud, unique society. The entire Ubykh nation—thirty thousand or more, men and women and children—chose freedom in exile, rather than submitting to genocide at the hands of the Tsars. But fleeing as refugees was just as difficult then as today, and thousands of Ubykhs died as a result of drowning and malnutrition and disease on the way to find refuge in the Ottoman Empire, where they were scattered once more. Dispersed across dozens of villages in what’s now the Turkish countryside, the Ubykh people were so thinly spread that their traditional society was no longer able to be sustained, and even their language, the very core of their culture, fell out of use so quickly that by the year 1964—just a hundred years after 30,000-odd Ubykhs were exiled—less than thirty Ubykhs still spoke their ancestral language competently, and the last fully competent speaker, Tevfik Esenç , died in 1992.

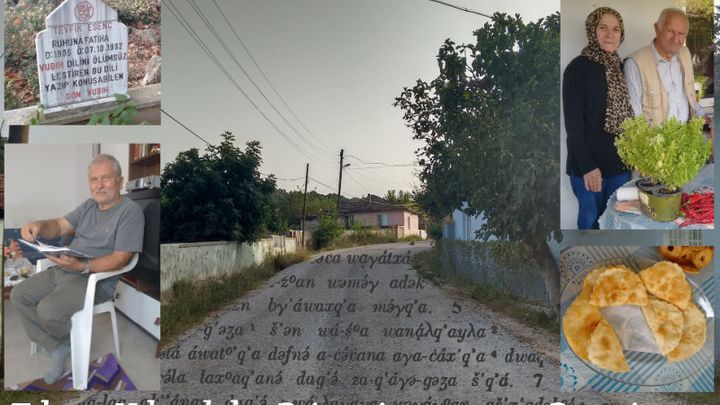

Tevfik Esenç, Ubykh's last fluent speaker. (Daily Sabah)

Tevfik Esenç, Ubykh's last fluent speaker. (Daily Sabah)

Fortunately, though, it was realised very early on that the Ubykh language was in serious trouble, so researchers spent most of the 20th century recording oral histories, cultural stories, folk-tales, and grammatical analysis, from dozens of the language’s last speakers. Ubykh also drew more and more attention from linguists as they began to appreciate its intricately complex grammar and sound system (even recognised in 1995 by a Guinness World Record for that reason). Written documentation and audio recordings exist in vast quantity, much of which is still waiting to be analysed. But while many surviving Ubykh people are intensely interested in reclaiming their language and culture, much of this information is sequestered in books and journals that modern Ubykhs can neither access nor read: most documentation was written in French, which virtually no living Ubykhs understand. Worse, no educational materials exist to teach the language; even now there is no comprehensive (or even adequate) Ubykh dictionary, and the last effort, in 1963 and also in French, is full of errors and fifty years out of date. Without these materials to help the Ubykhs revive their language and culture, both may be doomed to the dusty pages of history.

And that’s where I come in.

I’ve been researching surviving Ubykh records for nearly two decades, and have now collected almost all Ubykh research that’s ever been published; with these I’ve started developing a full set of Ubykh resources, the first of which was my reference grammar, published in 2011. But the central pillar of all my work is the compilation of a truly comprehensive dictionary, so that both learners and researchers alike will have a solid, consistent base on which to build a future for the language. This dictionary has taken seventeen years so far, and I’m starting to come in view of the finish line (you can see and download a sample chapter of the in-preparation dictionary here via Dropbox and here via Zenodo) . It's not only based on both published and unpublished recordings, and notes from various colleagues, but with the generous assistance of Tevfik Esenç’s grandson Burak, I’ve even been able to visit Ubykh villages in Turkey and speak with some of the last living people who remember any of the language at all; and with the kind offer to publish my dictionary by Professor Merab Chukhua of the Circassian Cultural Centre in Tbilisi, Georgia, I also have a venue for publication lined up. All that remains is for me to complete the work.

Partial speaker Özcan Komaç (right) and his wife Sevinç.

Partial speaker Özcan Komaç (right) and his wife Sevinç.

My work has all been self-funded up to this point, a labour of love and devotion towards this gorgeous linguistic marvel and the indomitable people who spoke it, who've captured my heart with their story and their courage. But unfortunately, my resources are finite, and even though my love for this language and its people runs very deep, I fear I may not be able to finish this dictionary and continue my work with the Ubykhs without outside assistance.

And that’s where you come in.

Again, my work with Ubykh is entirely self-funded. But an array of unexpected bills has sapped the last of my personal savings, and ongoing medical issues are eating up most of what I can spare. And there are still big things that have to be done. The archives of Georges Dumézil, who worked with the Ubykhs for more than fifty years, are still preserved in France and contain a lot of unpublished material, but the archives’ curators won’t allow these materials to be sent out of the country, so I have to access these at their French archive facilities. The archives of Georges Dumézil’s protégé, Georges Charachidzé, are also somewhere in France and contain a lot of Ubykh material; while there, I hope to negotiate gaining access to those as well. Also, I'm hoping to visit Turkey again to record as much as I can while it still remains possible to do so—the last few living partial speakers are now in their eighties, so time is of the essence for that. Unfortunately, almost all academic grants for salvage and revival work on minority languages are aimed at languages that are considered “endangered”. Since no fluent speakers are still alive, Ubykh is considered functionally “extinct” and so doesn’t qualify for institutional funding of this sort—even though many Ubykh people still survive, and want to preserve everything they can of their rich ancestral culture.

So, good denizens of the Internet, I’m reaching out to you instead: to friends, and family, and all people of good heart. I’m reaching out to you to ask for your help in supporting me as I finish my Ubykh dictionary, so that it can be published and given back to the Ubykh community, a tool for them to be able to revive not only their language, but their culture as well. This is a big, big ask and I know it, but I hope you’ll support my work for what I believe to be a truly worthy cause. My initial goal of $25,000 will permit me to travel to France and Turkey, as well as relieve logistical and medical bills over the course of twelve months, allowing me to dedicate my time to the dictionary. But any amount will be helpful, and if (by some miracle) donations exceed that amount, that'll allow me not only to complete the dictionary, but also start to expand my work into a concise learner's dictionary, a set of teaching manuals, an audio course, and perhaps even some translations of popular books.

All this depends on you, so thank you for your assistance! Please direct any questions or comments you may have to [email redacted], and I'll be happy to answer them.

Wan ṡ°əš°aq’ənạx!

In the aftermath of the great Caucasian War against Imperial Russia, in May 1864 the Ubykh people were expelled from their native lands on the Black Sea coast around the 2014 Winter Olympic city of Sochi, spelling the beginning of the end for a proud, unique society. The entire Ubykh nation—thirty thousand or more, men and women and children—chose freedom in exile, rather than submitting to genocide at the hands of the Tsars. But fleeing as refugees was just as difficult then as today, and thousands of Ubykhs died as a result of drowning and malnutrition and disease on the way to find refuge in the Ottoman Empire, where they were scattered once more. Dispersed across dozens of villages in what’s now the Turkish countryside, the Ubykh people were so thinly spread that their traditional society was no longer able to be sustained, and even their language, the very core of their culture, fell out of use so quickly that by the year 1964—just a hundred years after 30,000-odd Ubykhs were exiled—less than thirty Ubykhs still spoke their ancestral language competently, and the last fully competent speaker, Tevfik Esenç , died in 1992.

Tevfik Esenç, Ubykh's last fluent speaker. (Daily Sabah)

Tevfik Esenç, Ubykh's last fluent speaker. (Daily Sabah)Fortunately, though, it was realised very early on that the Ubykh language was in serious trouble, so researchers spent most of the 20th century recording oral histories, cultural stories, folk-tales, and grammatical analysis, from dozens of the language’s last speakers. Ubykh also drew more and more attention from linguists as they began to appreciate its intricately complex grammar and sound system (even recognised in 1995 by a Guinness World Record for that reason). Written documentation and audio recordings exist in vast quantity, much of which is still waiting to be analysed. But while many surviving Ubykh people are intensely interested in reclaiming their language and culture, much of this information is sequestered in books and journals that modern Ubykhs can neither access nor read: most documentation was written in French, which virtually no living Ubykhs understand. Worse, no educational materials exist to teach the language; even now there is no comprehensive (or even adequate) Ubykh dictionary, and the last effort, in 1963 and also in French, is full of errors and fifty years out of date. Without these materials to help the Ubykhs revive their language and culture, both may be doomed to the dusty pages of history.

And that’s where I come in.

I’ve been researching surviving Ubykh records for nearly two decades, and have now collected almost all Ubykh research that’s ever been published; with these I’ve started developing a full set of Ubykh resources, the first of which was my reference grammar, published in 2011. But the central pillar of all my work is the compilation of a truly comprehensive dictionary, so that both learners and researchers alike will have a solid, consistent base on which to build a future for the language. This dictionary has taken seventeen years so far, and I’m starting to come in view of the finish line (you can see and download a sample chapter of the in-preparation dictionary here via Dropbox and here via Zenodo) . It's not only based on both published and unpublished recordings, and notes from various colleagues, but with the generous assistance of Tevfik Esenç’s grandson Burak, I’ve even been able to visit Ubykh villages in Turkey and speak with some of the last living people who remember any of the language at all; and with the kind offer to publish my dictionary by Professor Merab Chukhua of the Circassian Cultural Centre in Tbilisi, Georgia, I also have a venue for publication lined up. All that remains is for me to complete the work.

Partial speaker Özcan Komaç (right) and his wife Sevinç.

Partial speaker Özcan Komaç (right) and his wife Sevinç.My work has all been self-funded up to this point, a labour of love and devotion towards this gorgeous linguistic marvel and the indomitable people who spoke it, who've captured my heart with their story and their courage. But unfortunately, my resources are finite, and even though my love for this language and its people runs very deep, I fear I may not be able to finish this dictionary and continue my work with the Ubykhs without outside assistance.

And that’s where you come in.

Again, my work with Ubykh is entirely self-funded. But an array of unexpected bills has sapped the last of my personal savings, and ongoing medical issues are eating up most of what I can spare. And there are still big things that have to be done. The archives of Georges Dumézil, who worked with the Ubykhs for more than fifty years, are still preserved in France and contain a lot of unpublished material, but the archives’ curators won’t allow these materials to be sent out of the country, so I have to access these at their French archive facilities. The archives of Georges Dumézil’s protégé, Georges Charachidzé, are also somewhere in France and contain a lot of Ubykh material; while there, I hope to negotiate gaining access to those as well. Also, I'm hoping to visit Turkey again to record as much as I can while it still remains possible to do so—the last few living partial speakers are now in their eighties, so time is of the essence for that. Unfortunately, almost all academic grants for salvage and revival work on minority languages are aimed at languages that are considered “endangered”. Since no fluent speakers are still alive, Ubykh is considered functionally “extinct” and so doesn’t qualify for institutional funding of this sort—even though many Ubykh people still survive, and want to preserve everything they can of their rich ancestral culture.

So, good denizens of the Internet, I’m reaching out to you instead: to friends, and family, and all people of good heart. I’m reaching out to you to ask for your help in supporting me as I finish my Ubykh dictionary, so that it can be published and given back to the Ubykh community, a tool for them to be able to revive not only their language, but their culture as well. This is a big, big ask and I know it, but I hope you’ll support my work for what I believe to be a truly worthy cause. My initial goal of $25,000 will permit me to travel to France and Turkey, as well as relieve logistical and medical bills over the course of twelve months, allowing me to dedicate my time to the dictionary. But any amount will be helpful, and if (by some miracle) donations exceed that amount, that'll allow me not only to complete the dictionary, but also start to expand my work into a concise learner's dictionary, a set of teaching manuals, an audio course, and perhaps even some translations of popular books.

All this depends on you, so thank you for your assistance! Please direct any questions or comments you may have to [email redacted], and I'll be happy to answer them.

Wan ṡ°əš°aq’ənạx!

Organizer

Rhona Fenwick

Organizer

Meadowbrook, QLD