Support an undergraduate researcher on her quest to conduct climate change field studies in Palau!

This project, in brief:

I was offered the opportunity to conduct climate research in Palau with a small group of oceanographers from the University of Washington. We are interested in finding out what Palau’s climate was like before satellites started tracking rainfall patterns to extend the record of natural climate variability, and have figured out how to do this looking closely at lake sediment. This information helps models of climate trends provide insights into how recent human activity has impacted rainfall patterns, and help nations in vulnerable locations, such as Palau, prepare for future changes.

I’ve worked in the lab with these inspirational oceanographers for the past two years, this the first chance I’ve had to go to the field to collect samples. In order to take advantage of this opportunity, a few things need to happen:

1. I need to prepare to be covered in mud on a daily basis – collecting sediment can be dirty business, you see.

2. I must read up on Semecarpus venenosus, a native Palauan plant affectionately referred to by its common name, “Poison Tree.”

3. Most importantly – I need to get there – which is where you come in!

Read on to find out more about the research I plan to do there, why it is important, and how YOU can help!

Where is Palau?

Palau is located around [7° N 134° E], which means a few things. First, the archipelago of Palau sits in the Western Pacific right by the equator, neighbored by Indonesia, the Philippines, and the rest of Micronesia. Second (and this is the part we care about!), Palau is located in the heart of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) which is a distinct band of heavy rainfall by the equator that spans the length of the Pacific Ocean.

Why is this research important?

Palau, as well as many Pacific island nations, declared a state of emergency due to the severe drought caused by El Niño in March. Citizens are only allowed access to tap water for three hours per day, schools are not open for entire days, and there is a pressing risk of running completely out of water.

Changes in the ITCZ can affect freshwater availability to people living on the islands in the South Pacific. The ICTZ is by no means a stationary rainfall feature – it can fluctuate in location as much as 500km and its tie to the climate-ocean interactions, such as El Niño and La Niña, inherently plays a role in island citizens’ freshwater access.

The satellite record shows precipitation patterns from the past 37 years, but the rainfall patterns before this point largely remain a mystery. So how do we investigate rainfall patterns in the tropics before 1979? We’ve found that the best way is to examine lake sediment! Knowing about the ITCZ of the past is key for predicting future rainfall patterns, upon which many island nations depend for freshwater access.

What does the Sachs Lab do?

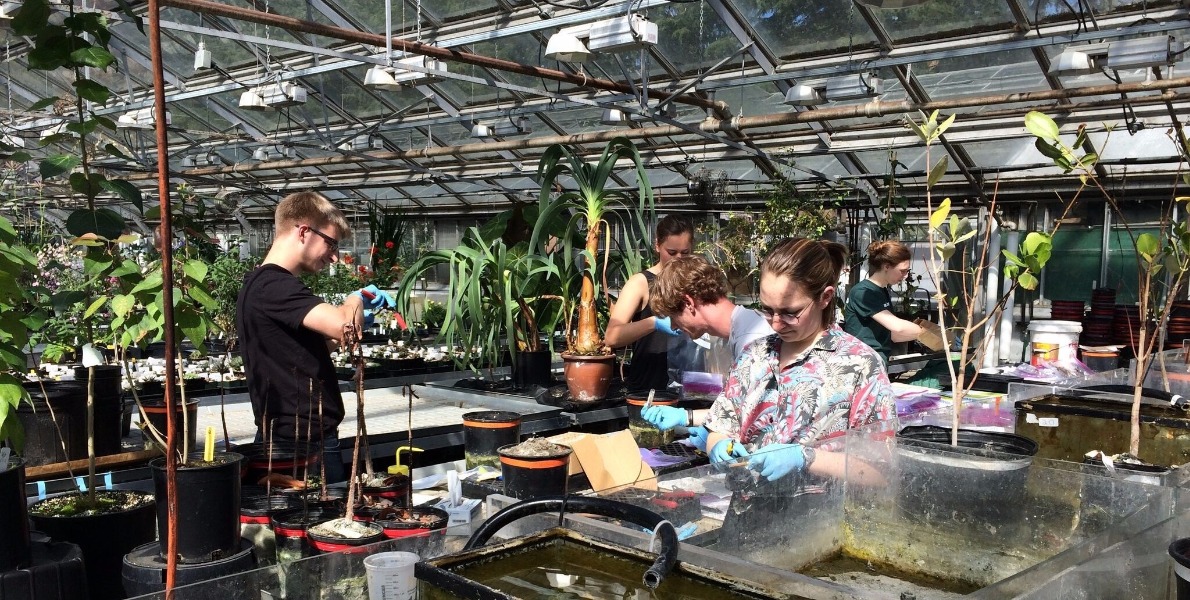

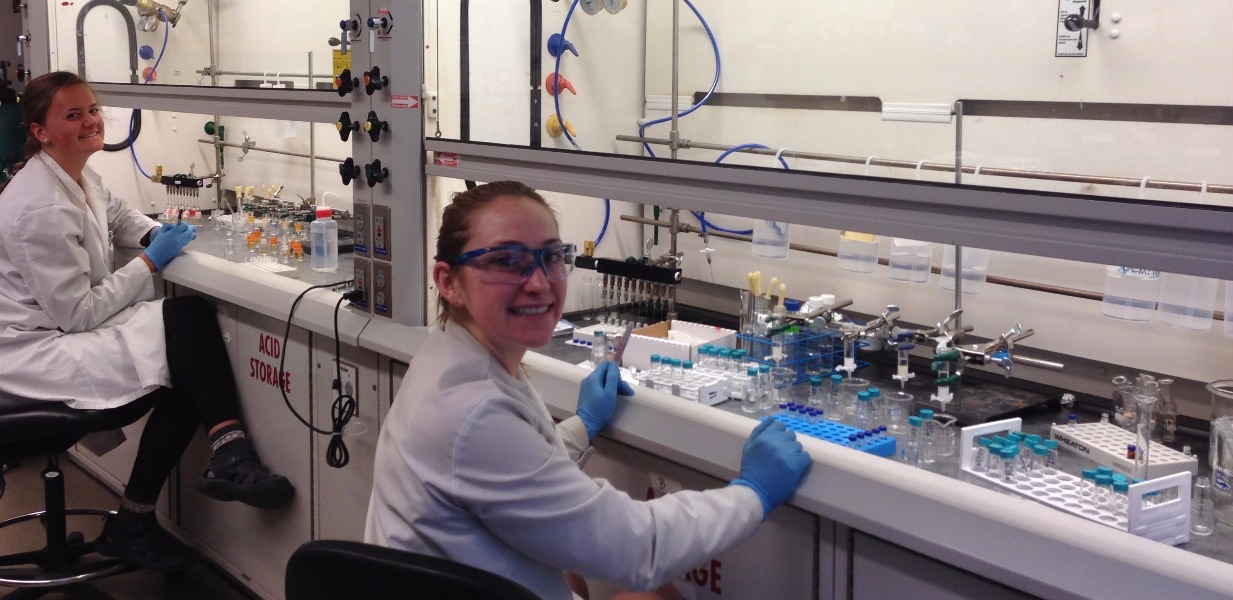

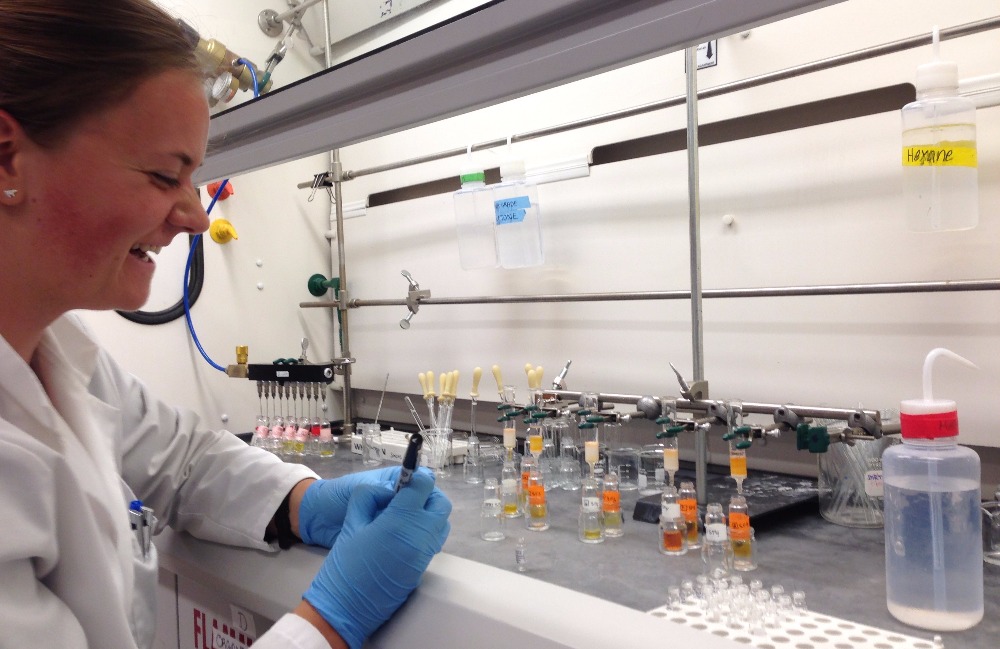

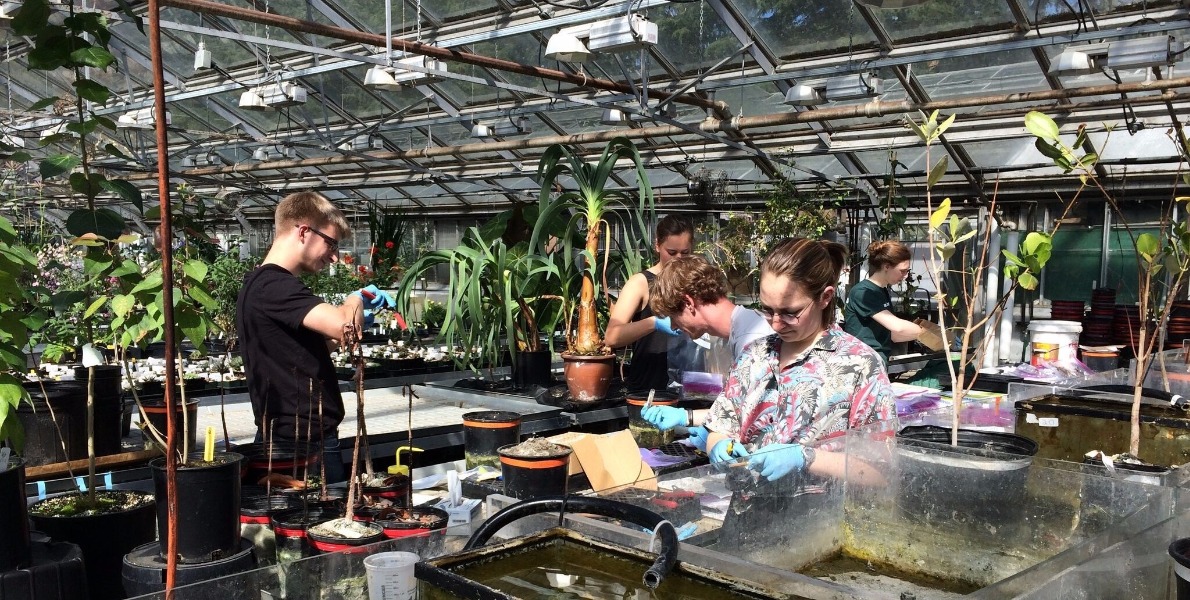

For the past two years I have had the pleasure of participating in research in an oceanography lab at the University of Washington. By looking at specific compounds in the lake sediment and seeing how their chemical compositions change over time, we are able to reconstruct rainfall patterns from the past 10,000 years. Paleoclimate models are important for predicting the effects of global warming and extreme climate patterns in the future.

Our research is focused on lakes that fall within the ITCZ and the rainfall feature to its southwest, the South Pacific Convergence Zone (SPCZ), as we are interested in how the size and locations of these climate features have changed during the Earth’s most recent epoch, the Holocene. We can use data from rainfall trends to predict future trends, which is especially important in quantifying human impacts on climate.

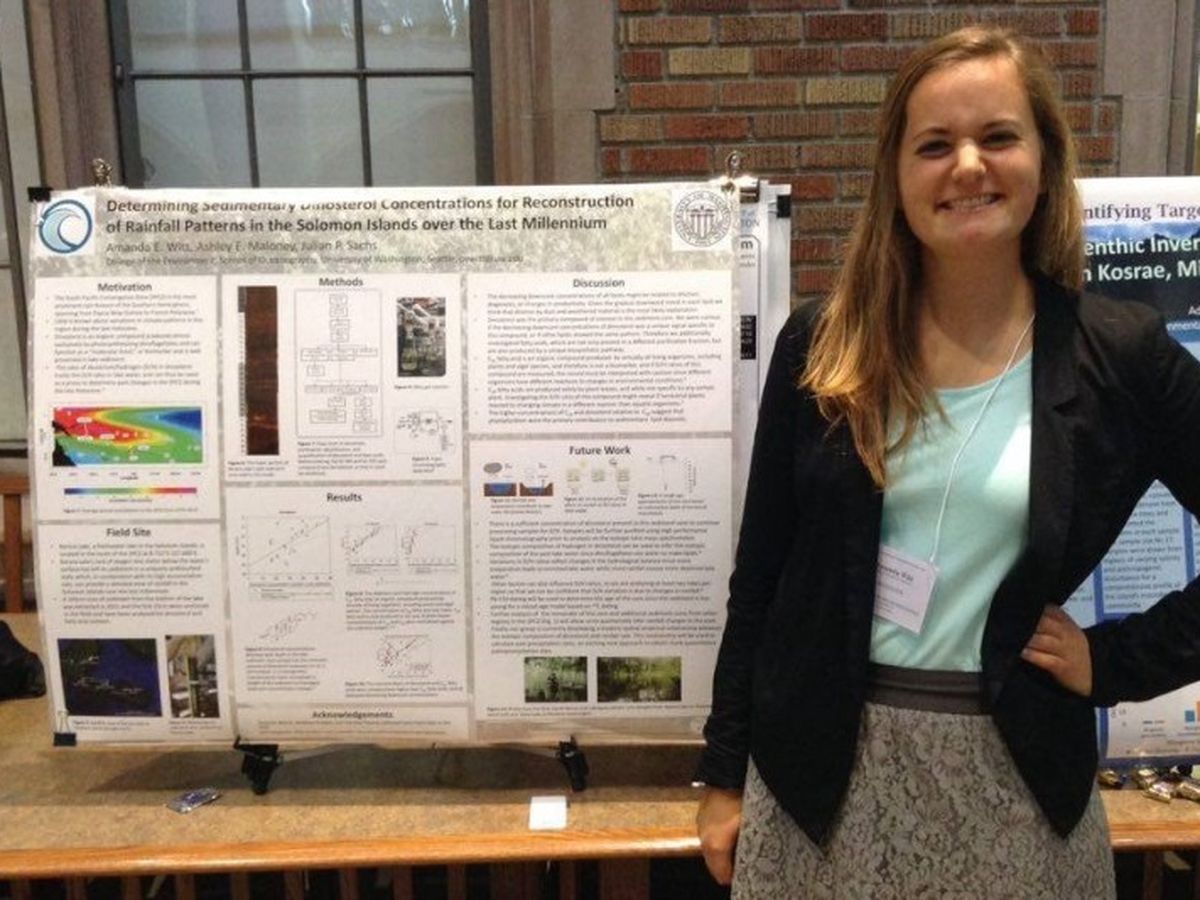

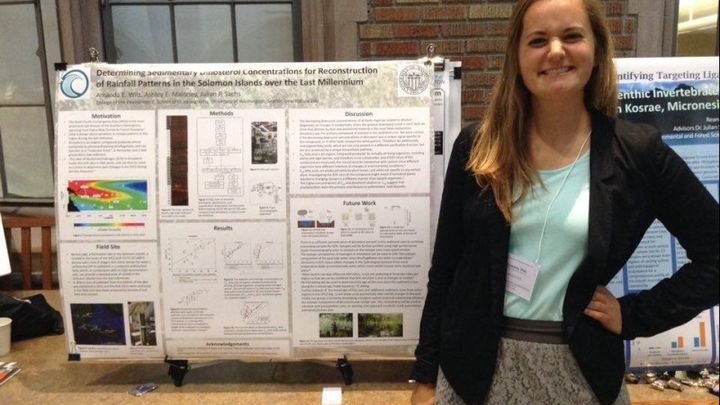

If you’re interested in getting the full scoop on what we can learn from lake sediment, you’re in luck! On Friday, May 20th, I will be giving a talk about what I have learned about the paleoclimate of the Solomon Islands at the Mary Gates Undergraduate Research Symposium at the University of Washington.

What’s a day in the life of a researcher in Palau?

Our schedules will go a little something like this:

· Wake up before the crack of dawn in the Coral Reef Research Foundation (CRRF) headquarters and get all of our equipment ready.

· Boat out to the limestone Rock Islands sprinkled throughout Palau until we arrive at an island with a marine lake.

· Trek through the tropical jungle of the island, gear in tow, bushwhacking through Poison Tree (that’s right, it’s exactly what it sounds like) and other Palauan flora until we arrive at the lake.

· Raft to the deepest part of the lake, set up a floating platform, and extract a few sediment cores from the bottom of the lake – which can be 10 meters long!

·Sediment cores strapped to our backs, we’ll bushwhack our way back to where our boat dropped us off and ride back to CRRF.

· Clean and organize the equipment, wash our Poison Tree-infested clothes, then head to bed in preparation to do it all again the next day.

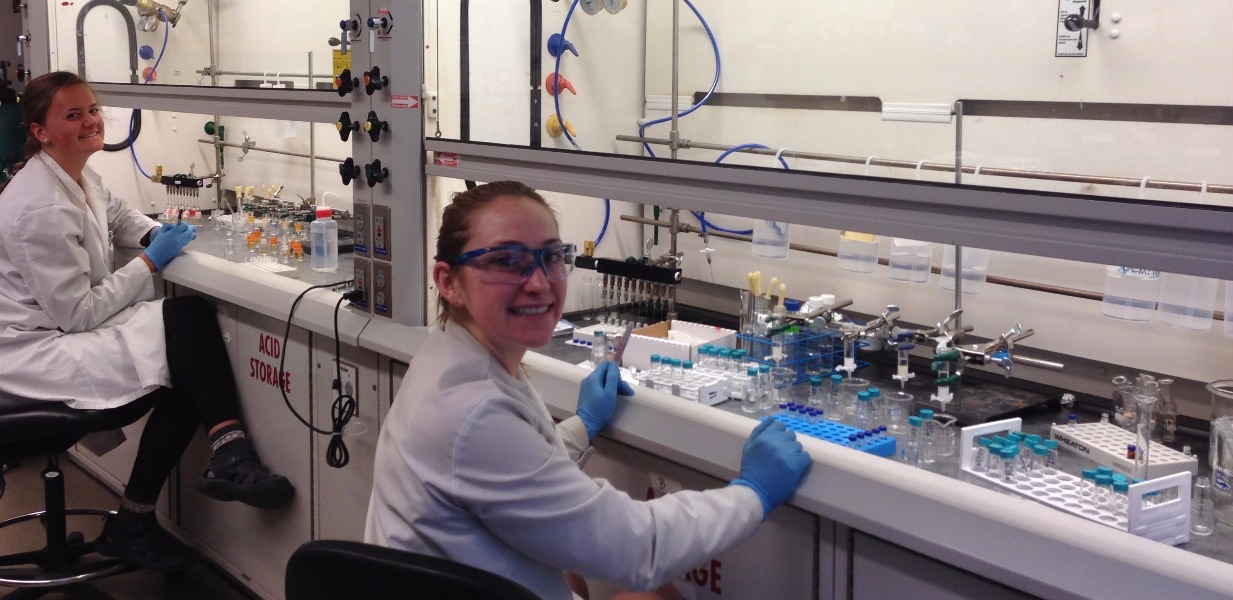

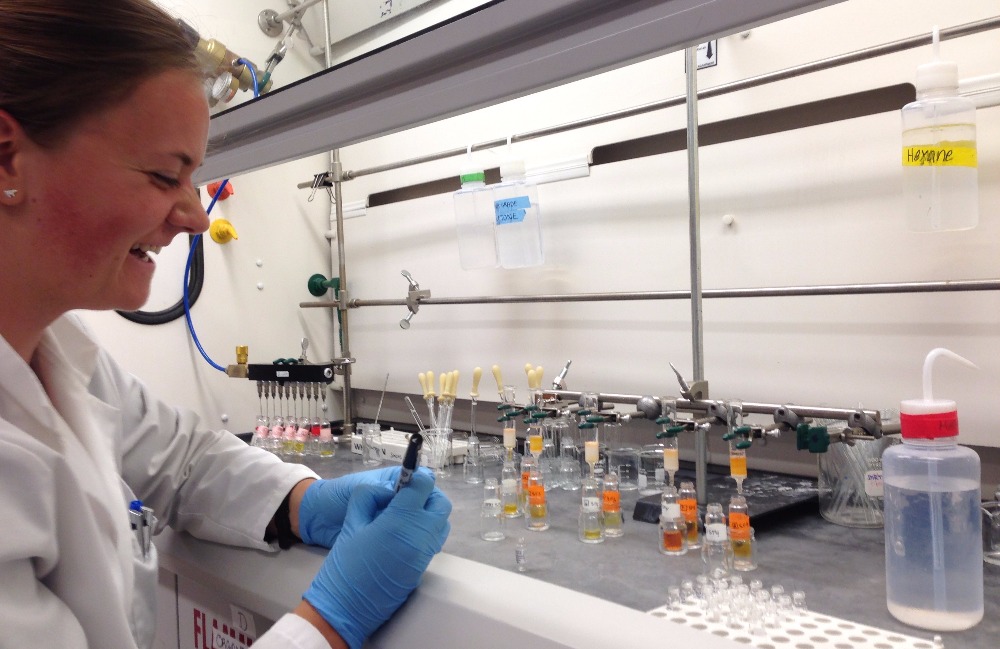

Back at the lab, we go through a very time-intensive process to isolate our compounds of interest from this sediment that involve many purification methods, including chromatography. Once these compounds are isolated, we look at their isotope ratios and use that information to reconstruct the paleoclimate!

Paleoclimate Dream Team Members:

Dr. Julian Sachs, the fearless principal investigator of the lab, is a Professor of Chemical Oceanography at the University of Washington and the research group leader behind the Palau project. His research focuses on the development of new classes of climate proxies based on isotope ratios found in molecular fossils. His extensive list of accomplishments is enough to make any aspiring academic weak in the knees – just take a look at his Curriculum Vitae!

Dr. Julian Sachs, the fearless principal investigator of the lab, is a Professor of Chemical Oceanography at the University of Washington and the research group leader behind the Palau project. His research focuses on the development of new classes of climate proxies based on isotope ratios found in molecular fossils. His extensive list of accomplishments is enough to make any aspiring academic weak in the knees – just take a look at his Curriculum Vitae!

Ashley Maloney, the most enthusiastic graduate student you’ll find in the University of Washington’s School of Oceanography. She has served patiently as my mentor over the past two years and has the knack for bringing out the inner paleoclimate nerd in everyone (that’s right, there’s a little paleoclimate nerd in you too! It just may be that you’ve never met Ashley to have it unleashed).

Ashley Maloney, the most enthusiastic graduate student you’ll find in the University of Washington’s School of Oceanography. She has served patiently as my mentor over the past two years and has the knack for bringing out the inner paleoclimate nerd in everyone (that’s right, there’s a little paleoclimate nerd in you too! It just may be that you’ve never met Ashley to have it unleashed).

Amanda Witt, that’s me! I’m an undergraduate in my fourth year of pursuing a double degree in General Biology and Spanish and a minor in Marine Biology at the University of Washington. Now you may be wondering, if she’s in her fourth year, isn’t she about to graduate? Short answer – no, as it turns out there is absolutely no overlap between my Biology and Spanish classes, so I’ll be at the UW for a bit more. But it’s ok – sticking around at UW leads to wonderful opportunities like this one! You also may ask yourself, I didn’t see “oceanography” on that academic medley, why is she in an oceanography lab? Well, it so happens that I got bit by the paleoclimatology bug (see “Ashley Maloney”) and have been unearthing my inner chemical oceanographer ever since. I am passionate about learning from the past to prepare for the future, and love working in a lab that applies this mentality to environmental issues.

Amanda Witt, that’s me! I’m an undergraduate in my fourth year of pursuing a double degree in General Biology and Spanish and a minor in Marine Biology at the University of Washington. Now you may be wondering, if she’s in her fourth year, isn’t she about to graduate? Short answer – no, as it turns out there is absolutely no overlap between my Biology and Spanish classes, so I’ll be at the UW for a bit more. But it’s ok – sticking around at UW leads to wonderful opportunities like this one! You also may ask yourself, I didn’t see “oceanography” on that academic medley, why is she in an oceanography lab? Well, it so happens that I got bit by the paleoclimatology bug (see “Ashley Maloney”) and have been unearthing my inner chemical oceanographer ever since. I am passionate about learning from the past to prepare for the future, and love working in a lab that applies this mentality to environmental issues.

Thanks for your help!

This is where GoFundMe comes in. There is a National Science Foundation grant that funds the research of Dr. Julian Sachs, along with other principal investigators who are researching different aspects of Palau and the changes it have undergone over time.

Unfortunately, the grant does not cover the costs of sending undergraduates to Palau. I’m hoping that I can reach my goal of $3000 on GoFundMe to cover the fill in the gap for travel expenses.

Hopefully after reading this you’ll feel inspired by the wonder of paleoclimatology! If you feel like donating to help me get to Palau, I will be forever grateful. Any donation, however large or small, is immensely appreciated!

If you’re unable to donate, that’s ok! You can help me reach my goal by sharing this page via Facebook or email to people who are passionate about the environment!

And don’t forget – if you want to hear my talk entitled “Using a Sterol Produced by Microalgae to Reconstruct Rainfall Patterns in the Solomon Islands”, stop by the Mary Gate Undergraduate Research Symposium on Friday, May 20th!

Feel free to contact me if you have any questions or want to learn more!

This project, in brief:

I was offered the opportunity to conduct climate research in Palau with a small group of oceanographers from the University of Washington. We are interested in finding out what Palau’s climate was like before satellites started tracking rainfall patterns to extend the record of natural climate variability, and have figured out how to do this looking closely at lake sediment. This information helps models of climate trends provide insights into how recent human activity has impacted rainfall patterns, and help nations in vulnerable locations, such as Palau, prepare for future changes.

I’ve worked in the lab with these inspirational oceanographers for the past two years, this the first chance I’ve had to go to the field to collect samples. In order to take advantage of this opportunity, a few things need to happen:

1. I need to prepare to be covered in mud on a daily basis – collecting sediment can be dirty business, you see.

2. I must read up on Semecarpus venenosus, a native Palauan plant affectionately referred to by its common name, “Poison Tree.”

3. Most importantly – I need to get there – which is where you come in!

Read on to find out more about the research I plan to do there, why it is important, and how YOU can help!

Where is Palau?

Palau is located around [7° N 134° E], which means a few things. First, the archipelago of Palau sits in the Western Pacific right by the equator, neighbored by Indonesia, the Philippines, and the rest of Micronesia. Second (and this is the part we care about!), Palau is located in the heart of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) which is a distinct band of heavy rainfall by the equator that spans the length of the Pacific Ocean.

Why is this research important?

Palau, as well as many Pacific island nations, declared a state of emergency due to the severe drought caused by El Niño in March. Citizens are only allowed access to tap water for three hours per day, schools are not open for entire days, and there is a pressing risk of running completely out of water.

Changes in the ITCZ can affect freshwater availability to people living on the islands in the South Pacific. The ICTZ is by no means a stationary rainfall feature – it can fluctuate in location as much as 500km and its tie to the climate-ocean interactions, such as El Niño and La Niña, inherently plays a role in island citizens’ freshwater access.

The satellite record shows precipitation patterns from the past 37 years, but the rainfall patterns before this point largely remain a mystery. So how do we investigate rainfall patterns in the tropics before 1979? We’ve found that the best way is to examine lake sediment! Knowing about the ITCZ of the past is key for predicting future rainfall patterns, upon which many island nations depend for freshwater access.

What does the Sachs Lab do?

For the past two years I have had the pleasure of participating in research in an oceanography lab at the University of Washington. By looking at specific compounds in the lake sediment and seeing how their chemical compositions change over time, we are able to reconstruct rainfall patterns from the past 10,000 years. Paleoclimate models are important for predicting the effects of global warming and extreme climate patterns in the future.

Our research is focused on lakes that fall within the ITCZ and the rainfall feature to its southwest, the South Pacific Convergence Zone (SPCZ), as we are interested in how the size and locations of these climate features have changed during the Earth’s most recent epoch, the Holocene. We can use data from rainfall trends to predict future trends, which is especially important in quantifying human impacts on climate.

If you’re interested in getting the full scoop on what we can learn from lake sediment, you’re in luck! On Friday, May 20th, I will be giving a talk about what I have learned about the paleoclimate of the Solomon Islands at the Mary Gates Undergraduate Research Symposium at the University of Washington.

What’s a day in the life of a researcher in Palau?

Our schedules will go a little something like this:

· Wake up before the crack of dawn in the Coral Reef Research Foundation (CRRF) headquarters and get all of our equipment ready.

· Boat out to the limestone Rock Islands sprinkled throughout Palau until we arrive at an island with a marine lake.

· Trek through the tropical jungle of the island, gear in tow, bushwhacking through Poison Tree (that’s right, it’s exactly what it sounds like) and other Palauan flora until we arrive at the lake.

· Raft to the deepest part of the lake, set up a floating platform, and extract a few sediment cores from the bottom of the lake – which can be 10 meters long!

·Sediment cores strapped to our backs, we’ll bushwhack our way back to where our boat dropped us off and ride back to CRRF.

· Clean and organize the equipment, wash our Poison Tree-infested clothes, then head to bed in preparation to do it all again the next day.

Back at the lab, we go through a very time-intensive process to isolate our compounds of interest from this sediment that involve many purification methods, including chromatography. Once these compounds are isolated, we look at their isotope ratios and use that information to reconstruct the paleoclimate!

Paleoclimate Dream Team Members:

Dr. Julian Sachs, the fearless principal investigator of the lab, is a Professor of Chemical Oceanography at the University of Washington and the research group leader behind the Palau project. His research focuses on the development of new classes of climate proxies based on isotope ratios found in molecular fossils. His extensive list of accomplishments is enough to make any aspiring academic weak in the knees – just take a look at his Curriculum Vitae!

Dr. Julian Sachs, the fearless principal investigator of the lab, is a Professor of Chemical Oceanography at the University of Washington and the research group leader behind the Palau project. His research focuses on the development of new classes of climate proxies based on isotope ratios found in molecular fossils. His extensive list of accomplishments is enough to make any aspiring academic weak in the knees – just take a look at his Curriculum Vitae!  Ashley Maloney, the most enthusiastic graduate student you’ll find in the University of Washington’s School of Oceanography. She has served patiently as my mentor over the past two years and has the knack for bringing out the inner paleoclimate nerd in everyone (that’s right, there’s a little paleoclimate nerd in you too! It just may be that you’ve never met Ashley to have it unleashed).

Ashley Maloney, the most enthusiastic graduate student you’ll find in the University of Washington’s School of Oceanography. She has served patiently as my mentor over the past two years and has the knack for bringing out the inner paleoclimate nerd in everyone (that’s right, there’s a little paleoclimate nerd in you too! It just may be that you’ve never met Ashley to have it unleashed). Amanda Witt, that’s me! I’m an undergraduate in my fourth year of pursuing a double degree in General Biology and Spanish and a minor in Marine Biology at the University of Washington. Now you may be wondering, if she’s in her fourth year, isn’t she about to graduate? Short answer – no, as it turns out there is absolutely no overlap between my Biology and Spanish classes, so I’ll be at the UW for a bit more. But it’s ok – sticking around at UW leads to wonderful opportunities like this one! You also may ask yourself, I didn’t see “oceanography” on that academic medley, why is she in an oceanography lab? Well, it so happens that I got bit by the paleoclimatology bug (see “Ashley Maloney”) and have been unearthing my inner chemical oceanographer ever since. I am passionate about learning from the past to prepare for the future, and love working in a lab that applies this mentality to environmental issues.

Amanda Witt, that’s me! I’m an undergraduate in my fourth year of pursuing a double degree in General Biology and Spanish and a minor in Marine Biology at the University of Washington. Now you may be wondering, if she’s in her fourth year, isn’t she about to graduate? Short answer – no, as it turns out there is absolutely no overlap between my Biology and Spanish classes, so I’ll be at the UW for a bit more. But it’s ok – sticking around at UW leads to wonderful opportunities like this one! You also may ask yourself, I didn’t see “oceanography” on that academic medley, why is she in an oceanography lab? Well, it so happens that I got bit by the paleoclimatology bug (see “Ashley Maloney”) and have been unearthing my inner chemical oceanographer ever since. I am passionate about learning from the past to prepare for the future, and love working in a lab that applies this mentality to environmental issues.

Thanks for your help!

This is where GoFundMe comes in. There is a National Science Foundation grant that funds the research of Dr. Julian Sachs, along with other principal investigators who are researching different aspects of Palau and the changes it have undergone over time.

Unfortunately, the grant does not cover the costs of sending undergraduates to Palau. I’m hoping that I can reach my goal of $3000 on GoFundMe to cover the fill in the gap for travel expenses.

Hopefully after reading this you’ll feel inspired by the wonder of paleoclimatology! If you feel like donating to help me get to Palau, I will be forever grateful. Any donation, however large or small, is immensely appreciated!

If you’re unable to donate, that’s ok! You can help me reach my goal by sharing this page via Facebook or email to people who are passionate about the environment!

And don’t forget – if you want to hear my talk entitled “Using a Sterol Produced by Microalgae to Reconstruct Rainfall Patterns in the Solomon Islands”, stop by the Mary Gate Undergraduate Research Symposium on Friday, May 20th!

Feel free to contact me if you have any questions or want to learn more!