Label the Occupation

Donation protected

In what might best be described as a nuanced decision (at least one Palestine-friendly lawyer considers it a victory), on May 5, 2021, the Canadian Federal Court of Appeal (FCA) dismissed the Trudeau government’s appeal of a lower court ruling that ‘Product of Israel’ labels on Israeli settlement wines are “false, misleading and deceptive,” all the while sending the labeling issue back to the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) for “reconsideration and redetermination.”

This time, the FCA ruled, the CFIA must consult with both the original complainant (David Kattenburg) and the settlement winery operating on stolen Palestinian land, then base its reformulated decision on Canadian consumer protection statutes.

Under pressure from the Trudeau government — passionate defender of Israel’s right to do whatever it wants — the CFIA may well dig deep for a reason to defend false labeling. Dr. Kattenburg will then be free to appeal, and the whole process will repeat itself, like one of those old psycho-horror flicks (or Groundhog Day), where the hero gets trapped in an existential loop.

On the other hand, perhaps the Court of Appeal's May 5 ruling is a victory after all. It’s complicated. Read on.

***

Letters of complaint often sink like a stone, with barely a ripple. Others set sail like a ship on a long voyage, arriving years later at some welcoming shore. A letter of mine to Canada’s largest liquor retailer, the Liquor Control Board of Ontario (LCBO), dashed off in early January 2017 with cc to the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA), is of the latter sort.

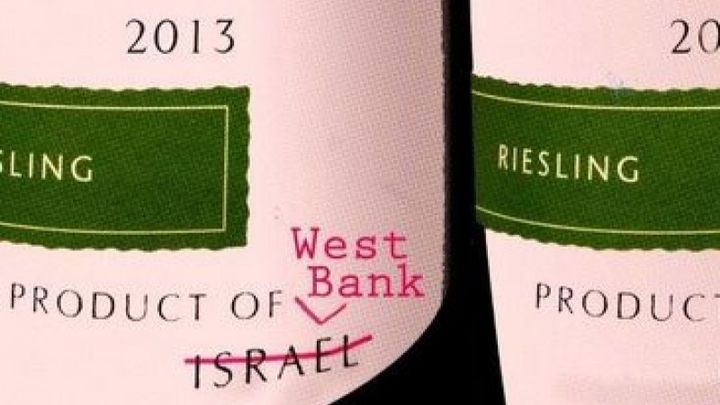

The object of my ire: a pair of LCBO wine products produced by Jewish settlers in the Israeli-colonized West Bank — labeled ‘Product of Israel’.

Where does Israel get off staking claim to stolen Palestinian lands on Canadian store shelves, I asked myself, pounding the keys of my laptop? How could the LCBO and Canadian government allow this?

Four years and four months later, on May 5, my wine labeling complaint was considered by the Canadian Federal Court of Appeal (FCA). A three-judge panel headed by Chief Justice Marc Noel heard arguments regarding a lower court ruling, back in July 2019, that ‘Product of Israel’ labels on settlement wines are “false, misleading and deceptive,” and an infringement of the Canadian Charter right to free speech through “conscientious” consumerism.

The Canadian government was Appellant in the hearing. I was the Respondent, ably defended by a true hero of human rights law, Dimitri Lascaris. Dimitri has devoted countless pro bono hours on this case, brilliantly arguing our case from all angles.

The FCA's May 5 ruling turned entirely on a concept I’ve learned about in the course of this legal odyssey of mine – the simple but open-ended idea of “reasonableness.”

In administrative law, no one is presumed to know more about regulatory statutes than federal regulators themselves – in my case, the Complaints and Appeals Office (CAO) of the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA). Reviewing judges are expected to defer to, rather than second-guess federal regulators.

In her July 2019 ruling, having established that the reasonableness standard applied in my case, Federal Court Justice Anne Mactavish argued that the CAO and CFIA had not acted reasonably in addressing my wine labeling complaint.

First, she opined, all parties (myself and the government, at that point) agreed that the ‘West Bank’ was in fact not part of Israel, so settlement wines could not reasonably be labeled as such.

The government’s claim that Canada’s free trade deal with Israel (CIFTA) justifies counterfactual labeling was also unreasonable, Mactavish wrote, because product labeling is not covered under the trade deal.

Mactavish’s third argument: The CAO had failed to take into account “freedom of expression issues” engaged in my original complaint, centering around the illegality of the settlements where the wines in question were produced. The Canadian Charter guarantees consumers the right to express views such as mine in their purchasing choices, and ‘Product of Israel’ labels infringe on that right.

“[It] is not appropriate for this Court to determine how the Settlement Wines should be labelled,” Justice Mactavish concluded [other than ‘Product of Israel’]. “That is a matter for the CFIA. Consequently, the recommendation made by the CAO is set aside, and the matter is remitted to the CAO for redetermination.”

Five months after the Mactavish ruling (days after the government filed its appeal memorandum), the Supreme Court of Canada issued a brand new framework for reasonableness review (Canada v. Vavilov) that further weakened the government’s appeal.

To begin with, Vavilov said, although administrative decision makers are experts in interpreting their governing statutes, their decisions must comply with statutory purpose and scope. When a decision maker strays beyond these, reasonability falls into question.

The decision maker must get it right. It must take the full “constellation of laws and facts” bearing on its decision into account, without ignoring or misapprehending key elements of the “factual matrix.” Among those decision makers are bound by — Canada’s international obligations under customary and conventional international law.

Naturally, a regulator’s reasons must be rational, internally coherent, transparent and fair, Vavilov says. They must obey common sense and logic and be free of flaws inconsistent with facts and law.

And of course, a regulator’s decisions cannot be fudged or “reverse-engineered,” for concealed or otherwise improper motives. It cannot adopt an interpretation it knows to be inferior – albeit plausible – merely because that interpretation is available and expedient.

What were the CFIA’s reasons for arriving at its decision in response to my wine labeling complaint back in January 2017, and for the CAO in upholding that decision?

In fact, the CFIA issued two totally opposite decisions. Its “Initial Decision” took six months to formulate. Over two hundred CFIA, Global Affairs Canada (GAC) and other government specialists got involved (I’ve assembled their names in a spreadsheet). Given the international trade and foreign policy dimensions of my complaint, CFIA specialists consulted with their GAC counterparts. Over the course of several weeks in April and May 2017, GAC trade specialists examined the matter. They confirmed Canada’s longstanding position that West Bank settlements violate the Fourth Geneva Convention, while impeding this “Two-State Solution” Ottawa claims to embrace.

GAC trade wonks gave CIFTA a close look. Product labeling provisions don’t appear anywhere in the trade deal, they found. Labeling was not among CIFTA’s “purposes.”

Diving deeper into the weeds, Trade Branch experts scrutinized the Oslo-era treaty that defines Israeli territory for the purposes of the trade deal. The 1995 Economic Protocol between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (Paris Accord) lays out trade and customs arrangements in ‘Palestinian Areas’ of the West Bank, but says nothing about settlements.

No big surprise. Settlements were off the table during Oslo’s “Interim Period.” Indeed, the declared purpose of the Paris Accord was to boost the Palestinian economy — not the profitability of settlements — in preparation for Palestinian statehood.

Having followed their analysis to its logical conclusion, in mid-May 2017, GAC specialists told their CFIA counterparts to forget about CIFTA. Product labeling and the trade deal were “two different things,” one specialist wrote in an email released to me under Access to Information. Instead, GAC experts said, the CFIA should rely on its own home statues, Canada’s Food and Drug Act and Consumer Packaging and Labeling Act — precisely what CFIA staff had been doing for the past four months.

Their analysis complete, on July 5, 2017, the CFIA informed the LCBO that ‘Product of Israel’ labels on settlement wines did not comply with federal consumer protection statutes, and asked the liquor retailer for an “action plan.” Early in the afternoon of July 11, 2017, the LCBO sent out a note to Ontario wine vendors that settlement wine products (from Shiloh and Psagot, in the northern West Bank) should cease to be imported or sold.

Within hours, an Israeli Embassy officer was on the horn. The Israeli government was hopping mad. Israel’s self-declared “staunch defender,” B’Nai Brith Canada, and the Centre for Israel and Jewish Affairs weighed in too, along with Liberal Member of Parliament Michael Levitt (now President and CEO of the Friends of Simon Wiesenthal Center). Israel and its advocates deluged the government with furious complaints, that rose right up to the Privy Council Office and Office of the Prime Minister.

Ian Shugart, Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs at the time (now Clerk of the Privy Council) sat down with CFIA President Paul Glover. Late on the afternoon of July 12, 2017, barely 24 hours after the release of the CFIA’s exhaustively researched determination on settlement wine labeling, Glover decided the ‘Initial Decision’ (as my attorney Dimitri Lascaris and I call it) would be rescinded. Enforcement of parliamentary statutes Mr. Glover’s agency is mandated to enforce would be waived, on behalf of a foreign ally and its Ottawa lobbyists.

“I have spoke [sic] with PCO and GAC (DM),” the besieged Glover emailed senior CFIA staff. “I don’t want CFIA issuing a statement that isn’t aligned with gov’t policy.”

What was that policy? Its most honest expression — deleted from the CFIA’s public mea culpa on the afternoon of July 13 – was part of the Certified Tribunal Record in my wine labeling case: “We respect all of our trade agreements and we very much value the Canada-Israel relationship.”

Amusingly, the same policy line was released to me by Global Affairs Canada, with that second independent clause redacted. GAC did not want me to know that Canada’s friendship with Israel trumps Canadian consumer protection statutes and solemn duties under international law.

Having identified paramount policy, all the CFIA needed to reverse engineer the desired wine labeling decision was an available and plausible rationale. Presto! The GAC now had “new information” about the Canada-Israel Free Trade Agreement. Under CIFTA, senior GAC officials told the CFIA, Israel’s customs area comprised the “West Bank.” Settlements are in the West Bank — ipso facto, ‘Product of Israel’ labeling was perfectly kosher. Q.E.D.

GAC and CFIA officials were aware of the sleight of hand, internal emails reveal.

Hours before the CFIA’s mea culpa went public, GAC’s most senior Middle East trade official told CFIA Vice-President Barbara Jordan that “[redacted] … are not mentioned explicitly” in the trade deal, and so the rationale for suspending enforcement of Canadian product labeling statutes should only make reference to “West Bank” products. Two weeks later, in response to a letter from me about the reversal (prior to the launching of my formal complaint to the CAO), the same GAC official told the same CFIA official that trade specialists were still not sure how to interpret the CIFTA customs area (i.e., whether settlements were part of the deal).

So, let’s review: The CFIA’s Reversal Decision was based on subject matter alien to the regulator’s legislated mandate and expertise, that it had therefore not reviewed or analyzed, and was motivated by an overarching government policy concealed from the complainant and general public.

Viewed through a Vavilov lens, the CFIA’s Initial Decision was eminently reasonable; the Reversal was anything but. The former was based on statutes and regulations no one knew more about than the CFIA, following months of exhaustive analysis and consultation. The latter was founded on foreign policy doctrine reasonableness review would consider inadmissible or improper.

As for the CFIA’s Complaints Office, it simply endorsed the reversal (what else could it have done?). No reasoning or analysis was involved; just capable canvassing, collation and word-smithing. In the course of its review of my complaint, the CAO never communicated with CFIA or GAC staff who had researched and drafted the Initial Decision. It certainly didn’t carry out its own analysis of the bogus CIFTA rationale, much less the Paris Protocol setting forth Israel’s alleged extended customs area.

“The CAO did not review matters relating to Canada’s foreign and trade policy, as these fall outside the mandate of both the CAO and CFIA,” the CAO’s director confessed in his closing letter to me in late September 2017, without a blush.

There’s no evidence the CAO ever saw the two week-long email exchange between CFIA team leaders and GAC specialists who had told the CFIA to forget about CIFTA, even though the exchange circulated among senior CFIA staff hours before the Reversal. Even though the exchange completely contradicted the CIFTA rationale for the Reversal.

Remarkably, there’s no evidence the CAO ever queried the CFIA about the most obvious reason for reversing, in a business day, a decision that had taken it five months to formulate: political pressure.

Under cross examination, the CFIA/CAO affiant to the Federal Court testified that he had never seen the July 12 email revealing that CFIA President Glover had rescinded the Initial Decision shortly after his meeting with Deputy Minister Shugart — obviously under intense political pressure — the evening before the CFIA’s formal “options” session.

For all of the above reasons, Canada’s Federal Court of Appeal had every reason to dismiss the government’s appeal of Justice Anne Mactavish’s July 2019 ruling on ‘Product of Israel’ settlement wines. Had it done so in its May 5 ruling — and left it at that — the outcome would have been clearer than it now actually is.

Instead, the FCA ruled that Justice Mactavish overstepped the bounds of reasonableness review, by “determining the proper outcome and providing the required justification [herself].”

The Court of Appeal’s remedy? The CFIA must go back to square one, reconsidering the wine labeling question based on submissions from both Dimitri and myself, as well as from Psagot Winery Ltd. and its CEO, Yaakov Berg, one of the settlement community’s most successful land thieves.

Sound like the 1945 psycho-horror film Dead of Night, or Bill Murray in Groundhog Day?

Perhaps not.

Among the enhanced submissions Dimitri and I will be putting forward to the CFIA this time around: evidence of the war crimes and crimes against humanity settlement profiteers like Psagot engage in — as presented to the International Criminal Court in its current investigation of Israel — and Canada’s obligations to uphold international humanitarian and human rights law.

Arguably the most compelling new evidence the CFIA will now be obliged to consider: Psagot Winery’s ‘Product of Israel’ reds and whites, trafficked on Canadian store shelves, are produced on lands Palestinians still hold title to.

In response to evidence submitted to the FCA by Psagot Winery (declared a full party last October), a responding affidavit was submitted by a Palestinian named Munif Treish (with assistance from the Palestinian human rights group Al-Haq). Munif is a retired civil engineer and current member of the City Council of Al-Bireh, a neighborhood of Ramallah right beside Psagot settlement. Munif’s affidavit is accompanied by land deeds issued by the Israeli Coordination and Civil Liaison Land Registry, establishing that Palestinians are the registered owners of the plots Psagot Winery now exploits, and has effectively stolen. Evidence of this sort has never been presented to either a Canadian government agency or court.

So, the FCA's May 5 decision may have painted the CFIA and its government masters into a corner.

Within minutes of today’s ruling, Toronto attorney Faisal Bhabha dashed off these up-beat thoughts to me and Dimitri:

“This is victory. The outcome is not as good as it could have been, but it is also far less bad than it could have been … The hope is that the [CFIA] has been sufficiently embarrassed by the whole affair and will not be susceptible to pressure from the Israel lobby. While the Court says that [Justice Mactavish’s] judgment is not binding on the Agency, it will be hard to ignore what she concluded, along with some helpful dicta from the FCA, such as: “While CIFTA can be informative, we do not know why the Agency concluded that it was determinative of the issue that it was required to decide under its labelling legislation.””

Thanks, Faisal. Our victory could have been sweeter.

In the expectation that full and complete justice will eventually be served — some time before Dimitri and I shuffle off this mortal coil — Al-Bireh landowners have invited me and my tireless attorney to come visit, to celebrate and break bread. If and when we do, my own quest for truth and justice – launched through a simple letter of complaint — will have arrived at a most welcoming shore.

For further details, please visit these three links:

https://dimitrilascaris.org/2017/10/25/fraudulently-labeled-product-of-israel-wines-challenged-in-federal-court-of-canada/

https://dimitrilascaris.org/2017/08/07/dr-david-kattenburg-files-appeal-from-canadian-food-inspection-agency-decision-to-allow-false-and-deceptive-labels-on-wines-from-illegal-israeli-settlements/

https://dimitrilascaris.org/2017/08/17/label-the-occupation-dr-david-kattenburg-files-further-material-with-the-cfias-complaints-appeals-office/

This time, the FCA ruled, the CFIA must consult with both the original complainant (David Kattenburg) and the settlement winery operating on stolen Palestinian land, then base its reformulated decision on Canadian consumer protection statutes.

Under pressure from the Trudeau government — passionate defender of Israel’s right to do whatever it wants — the CFIA may well dig deep for a reason to defend false labeling. Dr. Kattenburg will then be free to appeal, and the whole process will repeat itself, like one of those old psycho-horror flicks (or Groundhog Day), where the hero gets trapped in an existential loop.

On the other hand, perhaps the Court of Appeal's May 5 ruling is a victory after all. It’s complicated. Read on.

***

Letters of complaint often sink like a stone, with barely a ripple. Others set sail like a ship on a long voyage, arriving years later at some welcoming shore. A letter of mine to Canada’s largest liquor retailer, the Liquor Control Board of Ontario (LCBO), dashed off in early January 2017 with cc to the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA), is of the latter sort.

The object of my ire: a pair of LCBO wine products produced by Jewish settlers in the Israeli-colonized West Bank — labeled ‘Product of Israel’.

Where does Israel get off staking claim to stolen Palestinian lands on Canadian store shelves, I asked myself, pounding the keys of my laptop? How could the LCBO and Canadian government allow this?

Four years and four months later, on May 5, my wine labeling complaint was considered by the Canadian Federal Court of Appeal (FCA). A three-judge panel headed by Chief Justice Marc Noel heard arguments regarding a lower court ruling, back in July 2019, that ‘Product of Israel’ labels on settlement wines are “false, misleading and deceptive,” and an infringement of the Canadian Charter right to free speech through “conscientious” consumerism.

The Canadian government was Appellant in the hearing. I was the Respondent, ably defended by a true hero of human rights law, Dimitri Lascaris. Dimitri has devoted countless pro bono hours on this case, brilliantly arguing our case from all angles.

The FCA's May 5 ruling turned entirely on a concept I’ve learned about in the course of this legal odyssey of mine – the simple but open-ended idea of “reasonableness.”

In administrative law, no one is presumed to know more about regulatory statutes than federal regulators themselves – in my case, the Complaints and Appeals Office (CAO) of the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA). Reviewing judges are expected to defer to, rather than second-guess federal regulators.

In her July 2019 ruling, having established that the reasonableness standard applied in my case, Federal Court Justice Anne Mactavish argued that the CAO and CFIA had not acted reasonably in addressing my wine labeling complaint.

First, she opined, all parties (myself and the government, at that point) agreed that the ‘West Bank’ was in fact not part of Israel, so settlement wines could not reasonably be labeled as such.

The government’s claim that Canada’s free trade deal with Israel (CIFTA) justifies counterfactual labeling was also unreasonable, Mactavish wrote, because product labeling is not covered under the trade deal.

Mactavish’s third argument: The CAO had failed to take into account “freedom of expression issues” engaged in my original complaint, centering around the illegality of the settlements where the wines in question were produced. The Canadian Charter guarantees consumers the right to express views such as mine in their purchasing choices, and ‘Product of Israel’ labels infringe on that right.

“[It] is not appropriate for this Court to determine how the Settlement Wines should be labelled,” Justice Mactavish concluded [other than ‘Product of Israel’]. “That is a matter for the CFIA. Consequently, the recommendation made by the CAO is set aside, and the matter is remitted to the CAO for redetermination.”

Five months after the Mactavish ruling (days after the government filed its appeal memorandum), the Supreme Court of Canada issued a brand new framework for reasonableness review (Canada v. Vavilov) that further weakened the government’s appeal.

To begin with, Vavilov said, although administrative decision makers are experts in interpreting their governing statutes, their decisions must comply with statutory purpose and scope. When a decision maker strays beyond these, reasonability falls into question.

The decision maker must get it right. It must take the full “constellation of laws and facts” bearing on its decision into account, without ignoring or misapprehending key elements of the “factual matrix.” Among those decision makers are bound by — Canada’s international obligations under customary and conventional international law.

Naturally, a regulator’s reasons must be rational, internally coherent, transparent and fair, Vavilov says. They must obey common sense and logic and be free of flaws inconsistent with facts and law.

And of course, a regulator’s decisions cannot be fudged or “reverse-engineered,” for concealed or otherwise improper motives. It cannot adopt an interpretation it knows to be inferior – albeit plausible – merely because that interpretation is available and expedient.

What were the CFIA’s reasons for arriving at its decision in response to my wine labeling complaint back in January 2017, and for the CAO in upholding that decision?

In fact, the CFIA issued two totally opposite decisions. Its “Initial Decision” took six months to formulate. Over two hundred CFIA, Global Affairs Canada (GAC) and other government specialists got involved (I’ve assembled their names in a spreadsheet). Given the international trade and foreign policy dimensions of my complaint, CFIA specialists consulted with their GAC counterparts. Over the course of several weeks in April and May 2017, GAC trade specialists examined the matter. They confirmed Canada’s longstanding position that West Bank settlements violate the Fourth Geneva Convention, while impeding this “Two-State Solution” Ottawa claims to embrace.

GAC trade wonks gave CIFTA a close look. Product labeling provisions don’t appear anywhere in the trade deal, they found. Labeling was not among CIFTA’s “purposes.”

Diving deeper into the weeds, Trade Branch experts scrutinized the Oslo-era treaty that defines Israeli territory for the purposes of the trade deal. The 1995 Economic Protocol between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (Paris Accord) lays out trade and customs arrangements in ‘Palestinian Areas’ of the West Bank, but says nothing about settlements.

No big surprise. Settlements were off the table during Oslo’s “Interim Period.” Indeed, the declared purpose of the Paris Accord was to boost the Palestinian economy — not the profitability of settlements — in preparation for Palestinian statehood.

Having followed their analysis to its logical conclusion, in mid-May 2017, GAC specialists told their CFIA counterparts to forget about CIFTA. Product labeling and the trade deal were “two different things,” one specialist wrote in an email released to me under Access to Information. Instead, GAC experts said, the CFIA should rely on its own home statues, Canada’s Food and Drug Act and Consumer Packaging and Labeling Act — precisely what CFIA staff had been doing for the past four months.

Their analysis complete, on July 5, 2017, the CFIA informed the LCBO that ‘Product of Israel’ labels on settlement wines did not comply with federal consumer protection statutes, and asked the liquor retailer for an “action plan.” Early in the afternoon of July 11, 2017, the LCBO sent out a note to Ontario wine vendors that settlement wine products (from Shiloh and Psagot, in the northern West Bank) should cease to be imported or sold.

Within hours, an Israeli Embassy officer was on the horn. The Israeli government was hopping mad. Israel’s self-declared “staunch defender,” B’Nai Brith Canada, and the Centre for Israel and Jewish Affairs weighed in too, along with Liberal Member of Parliament Michael Levitt (now President and CEO of the Friends of Simon Wiesenthal Center). Israel and its advocates deluged the government with furious complaints, that rose right up to the Privy Council Office and Office of the Prime Minister.

Ian Shugart, Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs at the time (now Clerk of the Privy Council) sat down with CFIA President Paul Glover. Late on the afternoon of July 12, 2017, barely 24 hours after the release of the CFIA’s exhaustively researched determination on settlement wine labeling, Glover decided the ‘Initial Decision’ (as my attorney Dimitri Lascaris and I call it) would be rescinded. Enforcement of parliamentary statutes Mr. Glover’s agency is mandated to enforce would be waived, on behalf of a foreign ally and its Ottawa lobbyists.

“I have spoke [sic] with PCO and GAC (DM),” the besieged Glover emailed senior CFIA staff. “I don’t want CFIA issuing a statement that isn’t aligned with gov’t policy.”

What was that policy? Its most honest expression — deleted from the CFIA’s public mea culpa on the afternoon of July 13 – was part of the Certified Tribunal Record in my wine labeling case: “We respect all of our trade agreements and we very much value the Canada-Israel relationship.”

Amusingly, the same policy line was released to me by Global Affairs Canada, with that second independent clause redacted. GAC did not want me to know that Canada’s friendship with Israel trumps Canadian consumer protection statutes and solemn duties under international law.

Having identified paramount policy, all the CFIA needed to reverse engineer the desired wine labeling decision was an available and plausible rationale. Presto! The GAC now had “new information” about the Canada-Israel Free Trade Agreement. Under CIFTA, senior GAC officials told the CFIA, Israel’s customs area comprised the “West Bank.” Settlements are in the West Bank — ipso facto, ‘Product of Israel’ labeling was perfectly kosher. Q.E.D.

GAC and CFIA officials were aware of the sleight of hand, internal emails reveal.

Hours before the CFIA’s mea culpa went public, GAC’s most senior Middle East trade official told CFIA Vice-President Barbara Jordan that “[redacted] … are not mentioned explicitly” in the trade deal, and so the rationale for suspending enforcement of Canadian product labeling statutes should only make reference to “West Bank” products. Two weeks later, in response to a letter from me about the reversal (prior to the launching of my formal complaint to the CAO), the same GAC official told the same CFIA official that trade specialists were still not sure how to interpret the CIFTA customs area (i.e., whether settlements were part of the deal).

So, let’s review: The CFIA’s Reversal Decision was based on subject matter alien to the regulator’s legislated mandate and expertise, that it had therefore not reviewed or analyzed, and was motivated by an overarching government policy concealed from the complainant and general public.

Viewed through a Vavilov lens, the CFIA’s Initial Decision was eminently reasonable; the Reversal was anything but. The former was based on statutes and regulations no one knew more about than the CFIA, following months of exhaustive analysis and consultation. The latter was founded on foreign policy doctrine reasonableness review would consider inadmissible or improper.

As for the CFIA’s Complaints Office, it simply endorsed the reversal (what else could it have done?). No reasoning or analysis was involved; just capable canvassing, collation and word-smithing. In the course of its review of my complaint, the CAO never communicated with CFIA or GAC staff who had researched and drafted the Initial Decision. It certainly didn’t carry out its own analysis of the bogus CIFTA rationale, much less the Paris Protocol setting forth Israel’s alleged extended customs area.

“The CAO did not review matters relating to Canada’s foreign and trade policy, as these fall outside the mandate of both the CAO and CFIA,” the CAO’s director confessed in his closing letter to me in late September 2017, without a blush.

There’s no evidence the CAO ever saw the two week-long email exchange between CFIA team leaders and GAC specialists who had told the CFIA to forget about CIFTA, even though the exchange circulated among senior CFIA staff hours before the Reversal. Even though the exchange completely contradicted the CIFTA rationale for the Reversal.

Remarkably, there’s no evidence the CAO ever queried the CFIA about the most obvious reason for reversing, in a business day, a decision that had taken it five months to formulate: political pressure.

Under cross examination, the CFIA/CAO affiant to the Federal Court testified that he had never seen the July 12 email revealing that CFIA President Glover had rescinded the Initial Decision shortly after his meeting with Deputy Minister Shugart — obviously under intense political pressure — the evening before the CFIA’s formal “options” session.

For all of the above reasons, Canada’s Federal Court of Appeal had every reason to dismiss the government’s appeal of Justice Anne Mactavish’s July 2019 ruling on ‘Product of Israel’ settlement wines. Had it done so in its May 5 ruling — and left it at that — the outcome would have been clearer than it now actually is.

Instead, the FCA ruled that Justice Mactavish overstepped the bounds of reasonableness review, by “determining the proper outcome and providing the required justification [herself].”

The Court of Appeal’s remedy? The CFIA must go back to square one, reconsidering the wine labeling question based on submissions from both Dimitri and myself, as well as from Psagot Winery Ltd. and its CEO, Yaakov Berg, one of the settlement community’s most successful land thieves.

Sound like the 1945 psycho-horror film Dead of Night, or Bill Murray in Groundhog Day?

Perhaps not.

Among the enhanced submissions Dimitri and I will be putting forward to the CFIA this time around: evidence of the war crimes and crimes against humanity settlement profiteers like Psagot engage in — as presented to the International Criminal Court in its current investigation of Israel — and Canada’s obligations to uphold international humanitarian and human rights law.

Arguably the most compelling new evidence the CFIA will now be obliged to consider: Psagot Winery’s ‘Product of Israel’ reds and whites, trafficked on Canadian store shelves, are produced on lands Palestinians still hold title to.

In response to evidence submitted to the FCA by Psagot Winery (declared a full party last October), a responding affidavit was submitted by a Palestinian named Munif Treish (with assistance from the Palestinian human rights group Al-Haq). Munif is a retired civil engineer and current member of the City Council of Al-Bireh, a neighborhood of Ramallah right beside Psagot settlement. Munif’s affidavit is accompanied by land deeds issued by the Israeli Coordination and Civil Liaison Land Registry, establishing that Palestinians are the registered owners of the plots Psagot Winery now exploits, and has effectively stolen. Evidence of this sort has never been presented to either a Canadian government agency or court.

So, the FCA's May 5 decision may have painted the CFIA and its government masters into a corner.

Within minutes of today’s ruling, Toronto attorney Faisal Bhabha dashed off these up-beat thoughts to me and Dimitri:

“This is victory. The outcome is not as good as it could have been, but it is also far less bad than it could have been … The hope is that the [CFIA] has been sufficiently embarrassed by the whole affair and will not be susceptible to pressure from the Israel lobby. While the Court says that [Justice Mactavish’s] judgment is not binding on the Agency, it will be hard to ignore what she concluded, along with some helpful dicta from the FCA, such as: “While CIFTA can be informative, we do not know why the Agency concluded that it was determinative of the issue that it was required to decide under its labelling legislation.””

Thanks, Faisal. Our victory could have been sweeter.

In the expectation that full and complete justice will eventually be served — some time before Dimitri and I shuffle off this mortal coil — Al-Bireh landowners have invited me and my tireless attorney to come visit, to celebrate and break bread. If and when we do, my own quest for truth and justice – launched through a simple letter of complaint — will have arrived at a most welcoming shore.

For further details, please visit these three links:

https://dimitrilascaris.org/2017/10/25/fraudulently-labeled-product-of-israel-wines-challenged-in-federal-court-of-canada/

https://dimitrilascaris.org/2017/08/07/dr-david-kattenburg-files-appeal-from-canadian-food-inspection-agency-decision-to-allow-false-and-deceptive-labels-on-wines-from-illegal-israeli-settlements/

https://dimitrilascaris.org/2017/08/17/label-the-occupation-dr-david-kattenburg-files-further-material-with-the-cfias-complaints-appeals-office/

Organizer

David Kattenburg

Organizer

Hamilton, ON