Save Our History

Donation protected

In 2011 we unearthed evidence of a previously undiscovered station on the Underground Railroad at 530 Foxon Road in North Branford, Connecticut. The house appears to have been specifically designed and built to serve this purpose, the only one of its kind we’ve heard of. Its saga connects New York and Connecticut Abolitionists, a small farm, prominent New York businessmen and a famous architect in a secret network that protected them from the violent reprisal of the pro-slavery advocates of the day.

We feel strongly that we should preserve this history of the Abolitionists and the Underground Railroad. These people armed themselves with the intellectual legacy of the American Revolution and acted upon this moral conviction in the face of threats to their possessions, families and lives. Since their secret protected them, much of what they did remains secret to this day. We ask for your support in resurrecting and preserving this house and its history.

The mystery of the house was triggered first by our effort to reinforce the center carrying-beam in this small, oddly designed farmhouse. We uncovered two gravestones buried beneath the basement floor. This seemed like something to investigate: ghosts, murders, spirits? The mystery deepened when a neighbor related his childhood memory of playing in the basement in the 1960’s, finding a tunnel heading west toward the graveyard. We searched for signs of a hidden passageway in the basement. Stones in the western wall appeared to have been patched and repaired in a tunnel-sized shape, but we found no tunnel. Decaying mortar broke away in the southern wall and several basketball-sized stones fell to the floor. There was a hidden chamber behind the wall.

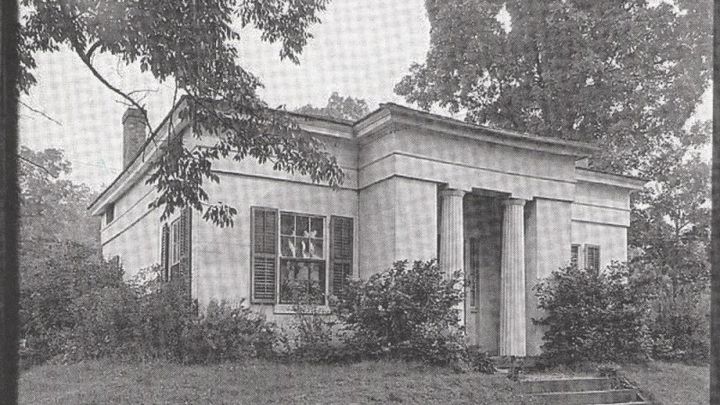

The hidden chamber ran under a large sandstone slab that forms the landing of the front entryway. Two prominent Greek columns frame the entryway, sitting atop this sandstone landing. Adjacent to the columns are compartments large enough for a person to climb into. Otherwise simply strange storage compartments, they reveal hidden ladders leading both down into the chamber below as well as up to the windowless portico above. A person hiding in one compartment could climb down into the chamber or up into the portico, then again into the opposite side, eluding detection by alternately hiding either beneath the stone stairs or in the portico above; an ingenious series of hiding places that seems to suit no other practical purpose.

The house was already in the National Register of Historic Places – it was designed by the famous New Haven architect/engineer - Ithiel Town. Its Greek columns distinguish it – a misplaced Greek temple in a sleepy farm town; a strangely small farmhouse fashioned in Ithiel Town’s classic “Greek Revival” style. But Town’s designs were much grander in scale: Connecticut’s original State Capitol building; North Carolina’s State Capitol building; Indiana’s Statehouse; the US Customs House (now Federal Hall in NYC); the US Capitol building; the Center and Trinity Churches on the New Haven Green – these are just a few examples of Town's prolific work. But 530 Foxon Road is “barely a cottage,” so why, for whom and for what did Town design it?

The house was built in 1832. But history reveals that the activity on the Underground Railroad occurred in the 1840s and 1850s. So we needed to connect a few dots to understand whether Abolitionists could have built it as part of the fledgling Underground Railroad in the early 1830s.

We traced the early lineage of the house to examine the players involved. Israel Baldwin, a church deacon, deeded 42 acres of his North Branford farm to his son Micah in 1827. For some reason Micah hired Ithiel Town to design the house. Construction was complete in 1832, but Micah never used it. Instead he deeded the house and land to his nephew George Baldwin in 1834. George was Micah’s nephew, the son of Josiah “George” Baldwin. There is nothing extraordinary in these transactions until these names are matched with the Abolitionist movement that soon followed.

In the 1830s the most prominent Abolitionist was New York businessman Arthur Tappan. He founded the American Abolitionist Society (AAS) in 1836. Each year representatives of the various state anti-slavery societies met at annual meetings of the AAS in New York City. Among them was a representative from Connecticut, “J.G. Baldwin.” This was Josiah “George” Baldwin, Micah’s brother. He represented Connecticut’s antislavery society and sat in the same room planning Abolitionist activities with the foremost Abolitionist of the day - Arthur Tappan.

Arthur Tappan’s brother and business partner – Lewis Tappan – was responsible for organizing and financing the defense of the captives of the Amistad in New Haven. He worked with Simeon Jocelyn of Connecticut to form the “Amistad Committee.” Simeon Jocelyn, a founding member of the Third Church of New Haven, sought and obtained the assistance of a New Haven attorney – Roger Sherman Baldwin. Attorney Baldwin, joined later by Yale graduates and former President John Quincy Adams, successfully defended the Africans’ right to freedom in the Amistad case. We have yet to connect this Baldwin to Israel, Josiah or Micah, but the following connections belie mere coincidence.

The Tappan brothers were business partners who for some time did quite well in the silk trade in New York City. It was widely known that they used their money to finance various Abolitionist organizations, colleges and seminaries. Their donations included funding for the Union Theological Seminary. Founded in 1835, it was dedicated to “the fierce and bitter agitation of the Anti-slavery and colonization questions…” On its board of directors was a prominent New Haven businessman: Micah Baldwin. Thus, both Baldwin brothers were directly involved in the prominent Abolitionist organizations of the 1830s.

Therefore, there is no question that the Baldwin brothers were Abolitionists who planned and built the house in the early years of the Underground Railroad. There is also no question that the house was specifically designed with secret hiding places that served no useful purpose but as hiding places that allowed for a person to escape even in the event of discovery. More yet, the man who designed the house , New Haven architect Ithiel Town, was also closely associated with the most famous Abolitionist leaders of the day - the Tappan brothers! In 1829 Town designed the neo-Classical building known as the “Counting House,” on 122 Pearl Street in New York City for Arthur and Lewis Tappan. It served as the Tappans’ warehouse and business center.

Because of their outgoing Abolitionist activities the Tappans’ lives and property were so repeatedly threatened by pro slavers that insurers refused to insure them or their businesses. This was widely publicized, perhaps as a threat to others who might otherwise join the cause. Knowing this, as the Tappans’ warehouse was burning to the ground in 1835, free African Americans rushed to save the Tappans’ property from the fire.

Since much of his work was done in the South, Ithiel Town did not let on that he was an Abolitionist. Yale’s archives reveal, however, that after his death, a wealth of Abolitionist literature was discovered in Town’s private library. Hence, in 1832, Town was not connected to the Abolitionist movement and was never publicly connected to the Baldwin house during his lifetime. It wasn’t until 1937 that the house was connected to Town, and then only because of its Greek revival design. And in 1832, the owner - George Baldwin – was simply a family farmer with only 42 acres, not directly connected to any anti-slavery cause. Those who were publicly connected to the Abolitionist movement – Micah and Josiah Baldwin – took great care to disassociate themselves from the house.

But we found direct evidence of Town’s secret connection to the house. One of the ceiling rafters in the house bears a large flamboyant signature hastily carved into the old-growth wood. Who would sign, but then conceal their signature beneath the lath and plaster? The first scrawling-script letter appears as a flamboyant “I” and the last name begins with a prominent “T.”

We initiated the rehabilitation of the structure in 2011: from decaying walls and floors to crumbling lead pipes and mortar; new plumbing and electric; leveling of the floors and restoration of its structural integrity. But the preservation of its historic merit remains.

We have yet to restore those aspects of the house that served the Underground Railroad or the many aspects of Ithiel Town’s original architectural design. The elements of its Greek revival design need be restored. The stone slabs forming the underground chamber need to be repositioned, restored and reinforced and the chamber cleaned, searched and further preserved. The chimneys have deteriorated and need repair. The compartments and hatchways need to be restored. The design element of its original balustrade was probably removed in the early 20th century and should be re-added. The Greek columns need to be restored and preserved. We will also seek to formally document the history of the house.

We believe that, when complete, the house should be open to the public. We plan to further establish lines of communication between other stations along the Underground Railroad and search for others that have not yet been discovered.

The funding we week is as follows: (i) foundation, passageways and underground chamber - $20,000; (ii); historical documentation, website and networking with other stations -$5,000 (iii) exterior Greek revival facades and roof $15,000; (iv) chimney and foundation restructuring - $15,000. Therefore, our total goal is $55,000.

We feel strongly that we should preserve this history of the Abolitionists and the Underground Railroad. These people armed themselves with the intellectual legacy of the American Revolution and acted upon this moral conviction in the face of threats to their possessions, families and lives. Since their secret protected them, much of what they did remains secret to this day. We ask for your support in resurrecting and preserving this house and its history.

The mystery of the house was triggered first by our effort to reinforce the center carrying-beam in this small, oddly designed farmhouse. We uncovered two gravestones buried beneath the basement floor. This seemed like something to investigate: ghosts, murders, spirits? The mystery deepened when a neighbor related his childhood memory of playing in the basement in the 1960’s, finding a tunnel heading west toward the graveyard. We searched for signs of a hidden passageway in the basement. Stones in the western wall appeared to have been patched and repaired in a tunnel-sized shape, but we found no tunnel. Decaying mortar broke away in the southern wall and several basketball-sized stones fell to the floor. There was a hidden chamber behind the wall.

The hidden chamber ran under a large sandstone slab that forms the landing of the front entryway. Two prominent Greek columns frame the entryway, sitting atop this sandstone landing. Adjacent to the columns are compartments large enough for a person to climb into. Otherwise simply strange storage compartments, they reveal hidden ladders leading both down into the chamber below as well as up to the windowless portico above. A person hiding in one compartment could climb down into the chamber or up into the portico, then again into the opposite side, eluding detection by alternately hiding either beneath the stone stairs or in the portico above; an ingenious series of hiding places that seems to suit no other practical purpose.

The house was already in the National Register of Historic Places – it was designed by the famous New Haven architect/engineer - Ithiel Town. Its Greek columns distinguish it – a misplaced Greek temple in a sleepy farm town; a strangely small farmhouse fashioned in Ithiel Town’s classic “Greek Revival” style. But Town’s designs were much grander in scale: Connecticut’s original State Capitol building; North Carolina’s State Capitol building; Indiana’s Statehouse; the US Customs House (now Federal Hall in NYC); the US Capitol building; the Center and Trinity Churches on the New Haven Green – these are just a few examples of Town's prolific work. But 530 Foxon Road is “barely a cottage,” so why, for whom and for what did Town design it?

The house was built in 1832. But history reveals that the activity on the Underground Railroad occurred in the 1840s and 1850s. So we needed to connect a few dots to understand whether Abolitionists could have built it as part of the fledgling Underground Railroad in the early 1830s.

We traced the early lineage of the house to examine the players involved. Israel Baldwin, a church deacon, deeded 42 acres of his North Branford farm to his son Micah in 1827. For some reason Micah hired Ithiel Town to design the house. Construction was complete in 1832, but Micah never used it. Instead he deeded the house and land to his nephew George Baldwin in 1834. George was Micah’s nephew, the son of Josiah “George” Baldwin. There is nothing extraordinary in these transactions until these names are matched with the Abolitionist movement that soon followed.

In the 1830s the most prominent Abolitionist was New York businessman Arthur Tappan. He founded the American Abolitionist Society (AAS) in 1836. Each year representatives of the various state anti-slavery societies met at annual meetings of the AAS in New York City. Among them was a representative from Connecticut, “J.G. Baldwin.” This was Josiah “George” Baldwin, Micah’s brother. He represented Connecticut’s antislavery society and sat in the same room planning Abolitionist activities with the foremost Abolitionist of the day - Arthur Tappan.

Arthur Tappan’s brother and business partner – Lewis Tappan – was responsible for organizing and financing the defense of the captives of the Amistad in New Haven. He worked with Simeon Jocelyn of Connecticut to form the “Amistad Committee.” Simeon Jocelyn, a founding member of the Third Church of New Haven, sought and obtained the assistance of a New Haven attorney – Roger Sherman Baldwin. Attorney Baldwin, joined later by Yale graduates and former President John Quincy Adams, successfully defended the Africans’ right to freedom in the Amistad case. We have yet to connect this Baldwin to Israel, Josiah or Micah, but the following connections belie mere coincidence.

The Tappan brothers were business partners who for some time did quite well in the silk trade in New York City. It was widely known that they used their money to finance various Abolitionist organizations, colleges and seminaries. Their donations included funding for the Union Theological Seminary. Founded in 1835, it was dedicated to “the fierce and bitter agitation of the Anti-slavery and colonization questions…” On its board of directors was a prominent New Haven businessman: Micah Baldwin. Thus, both Baldwin brothers were directly involved in the prominent Abolitionist organizations of the 1830s.

Therefore, there is no question that the Baldwin brothers were Abolitionists who planned and built the house in the early years of the Underground Railroad. There is also no question that the house was specifically designed with secret hiding places that served no useful purpose but as hiding places that allowed for a person to escape even in the event of discovery. More yet, the man who designed the house , New Haven architect Ithiel Town, was also closely associated with the most famous Abolitionist leaders of the day - the Tappan brothers! In 1829 Town designed the neo-Classical building known as the “Counting House,” on 122 Pearl Street in New York City for Arthur and Lewis Tappan. It served as the Tappans’ warehouse and business center.

Because of their outgoing Abolitionist activities the Tappans’ lives and property were so repeatedly threatened by pro slavers that insurers refused to insure them or their businesses. This was widely publicized, perhaps as a threat to others who might otherwise join the cause. Knowing this, as the Tappans’ warehouse was burning to the ground in 1835, free African Americans rushed to save the Tappans’ property from the fire.

Since much of his work was done in the South, Ithiel Town did not let on that he was an Abolitionist. Yale’s archives reveal, however, that after his death, a wealth of Abolitionist literature was discovered in Town’s private library. Hence, in 1832, Town was not connected to the Abolitionist movement and was never publicly connected to the Baldwin house during his lifetime. It wasn’t until 1937 that the house was connected to Town, and then only because of its Greek revival design. And in 1832, the owner - George Baldwin – was simply a family farmer with only 42 acres, not directly connected to any anti-slavery cause. Those who were publicly connected to the Abolitionist movement – Micah and Josiah Baldwin – took great care to disassociate themselves from the house.

But we found direct evidence of Town’s secret connection to the house. One of the ceiling rafters in the house bears a large flamboyant signature hastily carved into the old-growth wood. Who would sign, but then conceal their signature beneath the lath and plaster? The first scrawling-script letter appears as a flamboyant “I” and the last name begins with a prominent “T.”

We initiated the rehabilitation of the structure in 2011: from decaying walls and floors to crumbling lead pipes and mortar; new plumbing and electric; leveling of the floors and restoration of its structural integrity. But the preservation of its historic merit remains.

We have yet to restore those aspects of the house that served the Underground Railroad or the many aspects of Ithiel Town’s original architectural design. The elements of its Greek revival design need be restored. The stone slabs forming the underground chamber need to be repositioned, restored and reinforced and the chamber cleaned, searched and further preserved. The chimneys have deteriorated and need repair. The compartments and hatchways need to be restored. The design element of its original balustrade was probably removed in the early 20th century and should be re-added. The Greek columns need to be restored and preserved. We will also seek to formally document the history of the house.

We believe that, when complete, the house should be open to the public. We plan to further establish lines of communication between other stations along the Underground Railroad and search for others that have not yet been discovered.

The funding we week is as follows: (i) foundation, passageways and underground chamber - $20,000; (ii); historical documentation, website and networking with other stations -$5,000 (iii) exterior Greek revival facades and roof $15,000; (iv) chimney and foundation restructuring - $15,000. Therefore, our total goal is $55,000.

Organizer

Kirt Westfall

Organizer

North Branford, CT