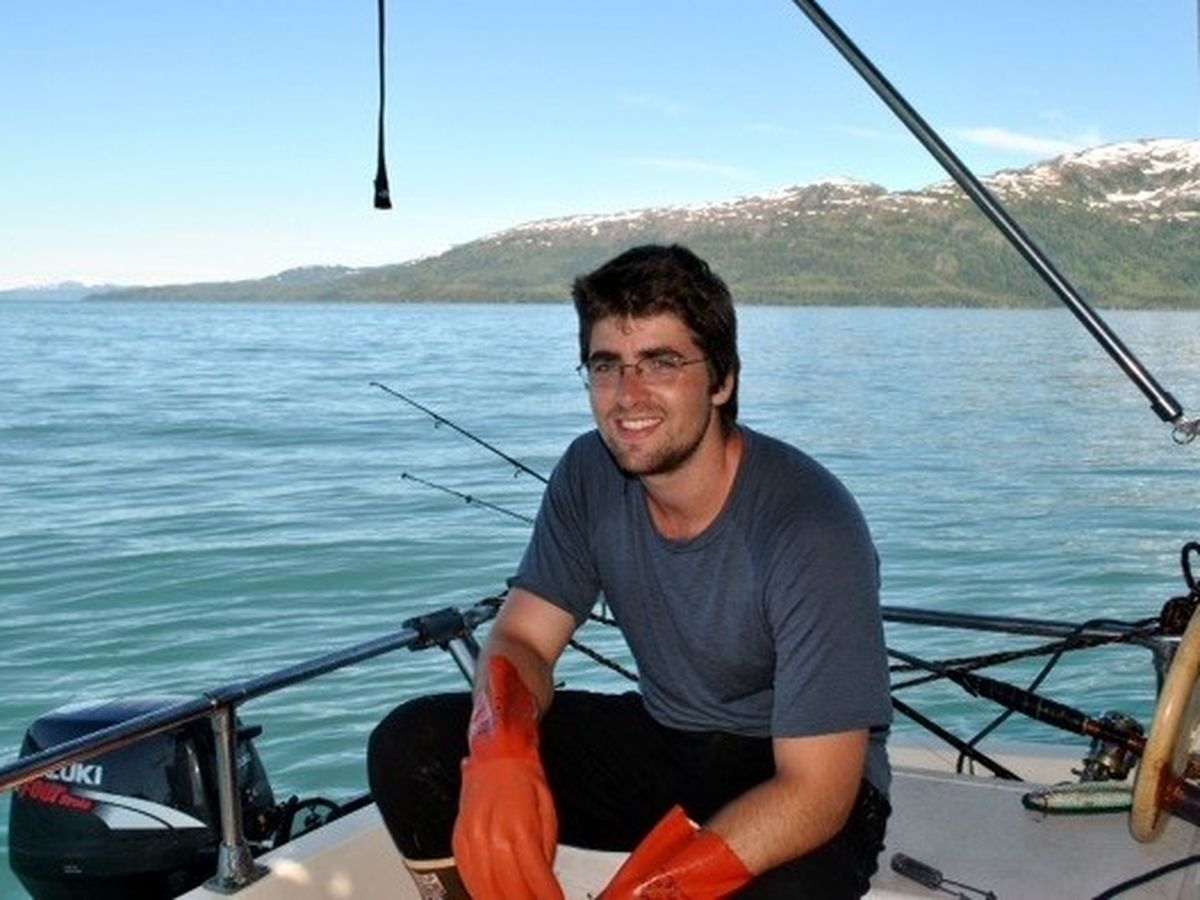

Our 27 year old son, Cody Roman Dial, disappeared on Costa Rica's Osa Peninsula in July 2014.

On the morning of July 9, seven months into an overland journey starting in Mexico, he wrote family and friends one of his usual emails outlining his plans. He said he planned to cross Corcovado National Park, a huge wilderness of rain forest, tropical coastline, and rugged mountains, alone for 4-5 days. He articulated his route and included a link to a map.

We had received similar emails about his solo crossing of Guatemala's Peten wilderness, a river trip descending to the Mosquito Coast of Honduras and Nicaragua, and a selection of volcanoes and canyons in between. These trips would last upwards of ten days and be followed up by articulate stories of the places and animals he had seen, the people he met, the experiences he'd had.

This time we did not receive the usual "I am out of the wilderness" email and on July 24, ten days after he should have been out, I contacted Corcovado National Park and the US Embassy in Costa Rica and reported him missing. Due to the way my emails were threaded, and the fact I had been away on my own trip, we didn't fully realize he had actually left on his trip until that day, July 24.

By July 26 I was in Puerto Jimenez where Cody Roman had written that he was shopping for food before his trip. With me was my Spanish speaking friend, Thai Verzone, who had dropped everything to come help me find my son. The night we arrived we discovered -- before the police, the Costa Rican Red Cross who was already searching for him, or the US Embassy -- the hostel he'd spent the night of July 8 and left his non-essential gear and personal items to lighten his load for his wilderness trip.

My wife Peggy and I had raised our son on wilderness and biological research trips around the world. By the time he arrived in Mexico in January 2014 he was no stranger to tropical rain forests. At three years old the two of us travelled to the Caribbean when I scouted my PhD research site for a rain forest experiment. At eight years old and as a family we spent three weeks at a research station deep in Indonesian Borneo. At 12 he had walked with my tropical ecology class across Corcovado. Now he was exploring the wildest areas of Central America.

From the beginning confusion surrounded the search in this remote, rural area where all "gringos look the same" to a countryside people who don't keep close attention to dates or time. There was another gringo who looked like Cody Roman but with a guide a week after he should have been out from his traverse and miles away from his planned route and outside the park.

Also confounding the search is an antagonsitic relationship between the Park Service and local gold miners, many of whom sneak into the park to mine illegally. My friend Thai encountered such an illegal gold miner who with three others had seen a gringo three hours from the end of the road on July 14, about when Cody Roman should have been ending his trip and running out of food.

This miner and his three companions are the only ones to describe a gringo who matches our son, his behavior, his equipment, and the fact that he was in a place that he'd likely have ended up given the terrain, his map and compass, and the network of illegal mining and poaching trails he would have encountered on his traverse.

As the Red Cross would not allow me to participate in their search, I was forced to fly friends down to help in my own clandestine search. I've spent nearly six weeks here in Costa Rica now as I write this. Over half of those days I have searched jungle trails and bushwhacked past vipers looking where he may be lost and injured, rappelled over waterfalls into inaccessible canyons where he may be trapped, tracked down miners hours from the road to interview them about gringos they'd seen. The other half I have talked to Red Cross; Park Servic; the Costa Rican version of the FBI called "OIJ"; powerful, political people in San Jose and the US; hung flyers all across the southern Osa Peninsula; and employed a private investigator.

After the first two weeks, including ten hours of helicopter time, the Red Cross and the Park Service announced they were pulling out. The helicopter would have helped lure an injured person into an opening but otherwise even with infrared sensors could not see past the multiple layers of leaves that make up the rain forest. The Red Cross had searched all the major valleys and ridges, to no avail. My friends and I had combed through the one square kilometer surrounding the area where Cody Roman had last been seen and found nothing. Together these searches suggested that maybe he was not lost and injured in the jungle, but rather the victim of foul play.

So to continue the search we are reaching out for donations. It's been two months. Perhaps a miner will find him or his equipment. Or perhaps someone will come forward with a story that leads to him. In any event we need to keep the search alive.

On the morning of July 9, seven months into an overland journey starting in Mexico, he wrote family and friends one of his usual emails outlining his plans. He said he planned to cross Corcovado National Park, a huge wilderness of rain forest, tropical coastline, and rugged mountains, alone for 4-5 days. He articulated his route and included a link to a map.

We had received similar emails about his solo crossing of Guatemala's Peten wilderness, a river trip descending to the Mosquito Coast of Honduras and Nicaragua, and a selection of volcanoes and canyons in between. These trips would last upwards of ten days and be followed up by articulate stories of the places and animals he had seen, the people he met, the experiences he'd had.

This time we did not receive the usual "I am out of the wilderness" email and on July 24, ten days after he should have been out, I contacted Corcovado National Park and the US Embassy in Costa Rica and reported him missing. Due to the way my emails were threaded, and the fact I had been away on my own trip, we didn't fully realize he had actually left on his trip until that day, July 24.

By July 26 I was in Puerto Jimenez where Cody Roman had written that he was shopping for food before his trip. With me was my Spanish speaking friend, Thai Verzone, who had dropped everything to come help me find my son. The night we arrived we discovered -- before the police, the Costa Rican Red Cross who was already searching for him, or the US Embassy -- the hostel he'd spent the night of July 8 and left his non-essential gear and personal items to lighten his load for his wilderness trip.

My wife Peggy and I had raised our son on wilderness and biological research trips around the world. By the time he arrived in Mexico in January 2014 he was no stranger to tropical rain forests. At three years old the two of us travelled to the Caribbean when I scouted my PhD research site for a rain forest experiment. At eight years old and as a family we spent three weeks at a research station deep in Indonesian Borneo. At 12 he had walked with my tropical ecology class across Corcovado. Now he was exploring the wildest areas of Central America.

From the beginning confusion surrounded the search in this remote, rural area where all "gringos look the same" to a countryside people who don't keep close attention to dates or time. There was another gringo who looked like Cody Roman but with a guide a week after he should have been out from his traverse and miles away from his planned route and outside the park.

Also confounding the search is an antagonsitic relationship between the Park Service and local gold miners, many of whom sneak into the park to mine illegally. My friend Thai encountered such an illegal gold miner who with three others had seen a gringo three hours from the end of the road on July 14, about when Cody Roman should have been ending his trip and running out of food.

This miner and his three companions are the only ones to describe a gringo who matches our son, his behavior, his equipment, and the fact that he was in a place that he'd likely have ended up given the terrain, his map and compass, and the network of illegal mining and poaching trails he would have encountered on his traverse.

As the Red Cross would not allow me to participate in their search, I was forced to fly friends down to help in my own clandestine search. I've spent nearly six weeks here in Costa Rica now as I write this. Over half of those days I have searched jungle trails and bushwhacked past vipers looking where he may be lost and injured, rappelled over waterfalls into inaccessible canyons where he may be trapped, tracked down miners hours from the road to interview them about gringos they'd seen. The other half I have talked to Red Cross; Park Servic; the Costa Rican version of the FBI called "OIJ"; powerful, political people in San Jose and the US; hung flyers all across the southern Osa Peninsula; and employed a private investigator.

After the first two weeks, including ten hours of helicopter time, the Red Cross and the Park Service announced they were pulling out. The helicopter would have helped lure an injured person into an opening but otherwise even with infrared sensors could not see past the multiple layers of leaves that make up the rain forest. The Red Cross had searched all the major valleys and ridges, to no avail. My friends and I had combed through the one square kilometer surrounding the area where Cody Roman had last been seen and found nothing. Together these searches suggested that maybe he was not lost and injured in the jungle, but rather the victim of foul play.

So to continue the search we are reaching out for donations. It's been two months. Perhaps a miner will find him or his equipment. Or perhaps someone will come forward with a story that leads to him. In any event we need to keep the search alive.