Have they told you?

Have they told you? – Educating far-flung Indonesia

Original campaign text uploaded mid-2016

Intent –

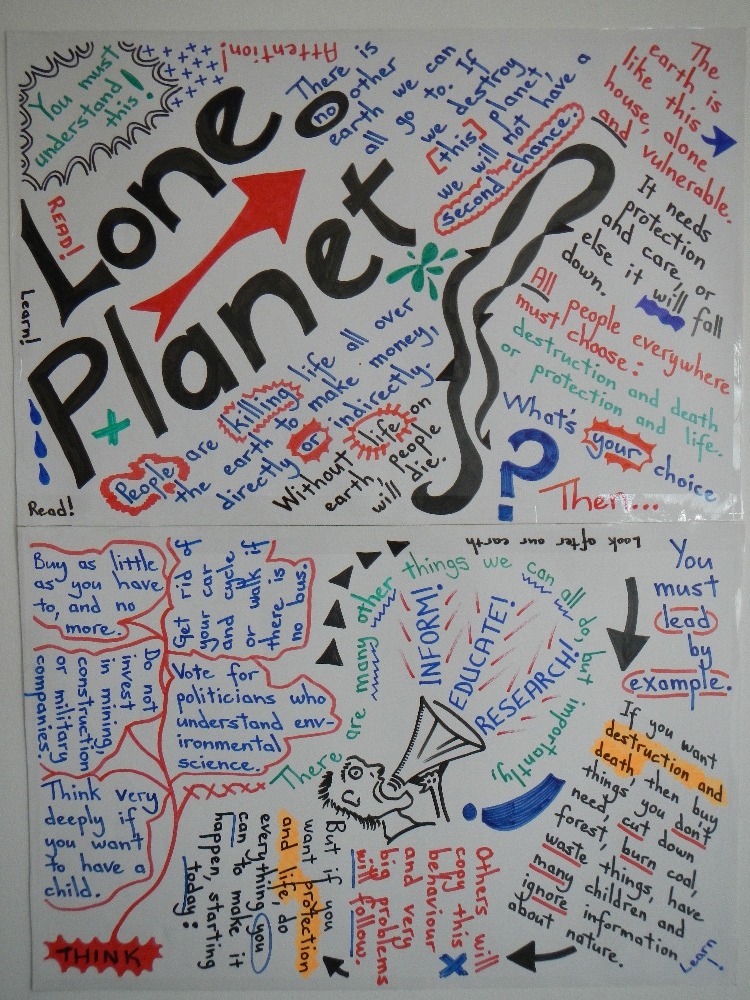

· Rural Indonesia is experiencing a circus of ecological destruction by armed workers, corrupt officials, big money and mercenaries.

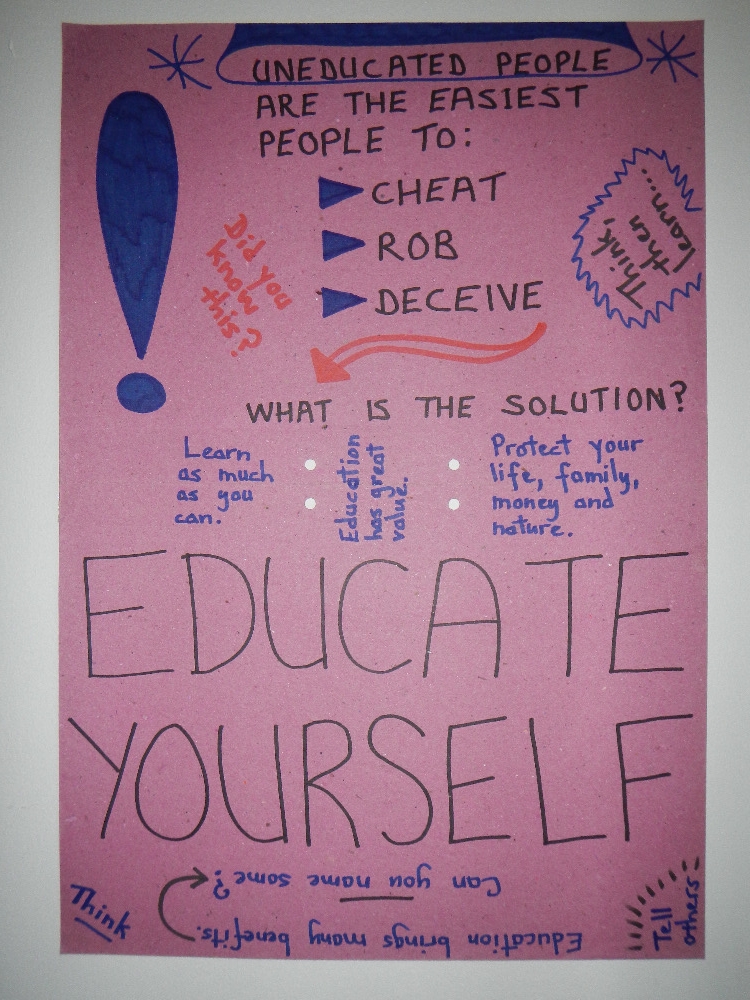

· To combat this, Have they told you? aims to deliver environmental education the current government school curriculum isn’t.

Content –

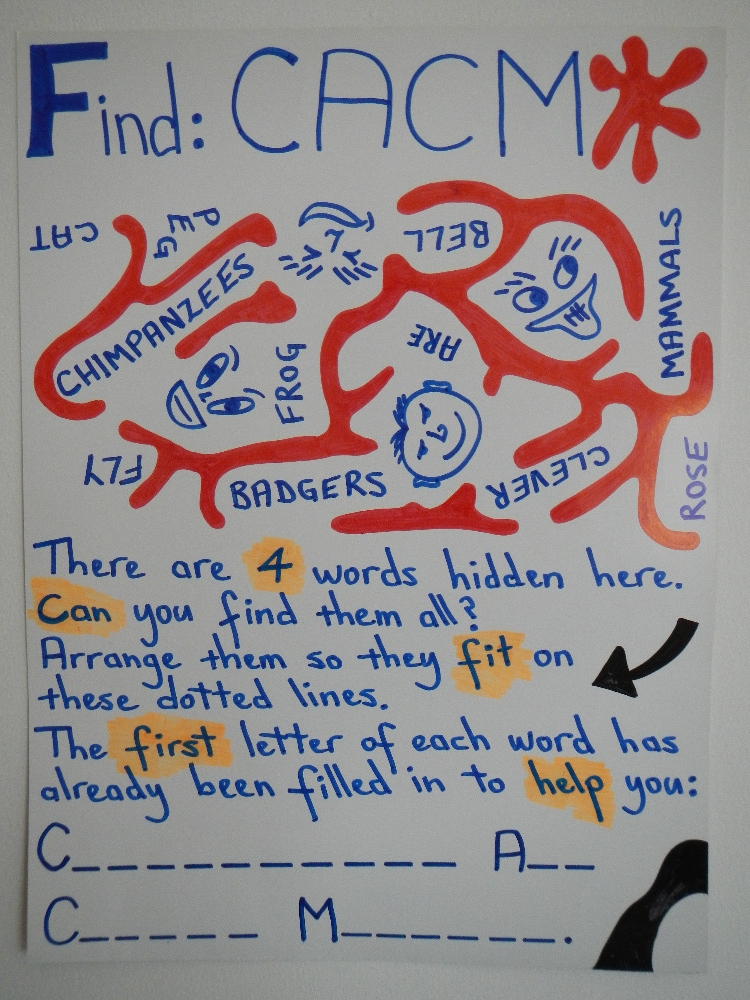

· A world record for the “Largest collection of hand-made educational items” in batches of 1,001 is being attempted.

· All use English-Bahasa Indonesia translations and will be downloadable.

· These need to reach children in communities where the government’s own education system has difficulty penetrating.

Appeal –

· This is currently propped up by Alastair Galpin’s and Nila Adha’s limited personal money.

· Developing such education for one of the largest school-going populations is beyond their financial means.

· The team knows environmental education is imperative.

· Donate between GBP 5 and GBP 50,000 and receive the associated level of rewards.

Funds are being raised towards day-to-day running costs, overheads, professional services, excursions, and the formation of a legal foundation. Only the two on-site team members can withdraw from the project account. This snapshot of finances shows all costs for the period 5 December – 29 December 2015. Alastair had to fly to Singapore then as required by Indonesian immigration regulations. This gives an example of project activities over a period of several weeks.

Have they told you? – Educating far-flung Indonesia

Instilling a sense of pride and community through environmental education:

· In Indonesia, proper environmental education isn’t presently taught in government schools. This mostly affects children under 15 years, which is about a quarter of the population [1].

· The country is declining towards social turmoil because the natural resources its 256 million people [1] depend upon are being rapidly destroyed.

· Have they told you? is a private environmental education self-starter which attempts to fill this huge void in Indonesia’s government school curriculum.

Alastair Galpin of WorldRecordChase.com believes Millennium Development Goals (2, Target 2A, and 7, Target 7A and 7B) [2] remain unattainable in far-flung Indonesia, due, in large part, to these communities not receiving basic environmental education. Here are excerpts of these goals. To help make them part of life in Indonesia, Alastair and his team have started creating environmental education lessons. Join them, and be a part of turning this situation around.

What are the dangers of a lack of environmental education?

Leading voices including Jared Diamond [3] and David Suzuki [4] caution that environmental collapse leads to social collapse. Serious damage to the environment triggers a toxic cycle of disease, poverty, civil strife and draconian governmental responses. The foundations of such a scenario are forming in far-flung Indonesian communities, and this affects the rest of the world.

How? Most adults in developed countries have an idea of how environmental challenges will impact society during this century. In developing nations, which face the world’s toughest environmental problems, awareness on this issue is perilously low. Take a look at the videos below. They compellingly demonstrate why environmental education for developing nations is urgently needed:

· Jared Diamond: Why societies collapse;

· One Minute to Midnight – David Suzuki on limits to growth & overconsumption;

· Will humankind survive the century?;

· Severn Cullis-Suzuki at Rio Summit 1992.

Importantly, Alastair understands that both the international climate change deniers and doomsday fraternities may hold incorrect beliefs. Much in-fighting and misinformation dissemination also splinters the scientific community and the public at large at times on these issues. Even so, mankind’s irresponsible destruction of life across the earth is unacceptable behaviour. It must be drastically curbed.

Public environmental education is a very important key, and that’s driving Alastair’s passion on this project.

Despite the negative socio-environmental trajectory in far-flung Indonesia, Alastair and his helpers are making good progress. A youth aspiring to own a coal mine has been persuaded otherwise, several local children have begun separating their waste, and a farmer’s sons have started fertilising their crops with vegetable scraps.

Heartwarming support is trickling in from companies, organisations, individuals, think tanks and government officials. To the team, these are signs of hope.

Why Indonesia?

Indonesia ranks 110th - lower than Russia, Kazakhstan and Palestine - out of nearly 200 countries on the Human Development Index [5], a key measure of citizens’ welfare. Its economy depends largely on extractive industries including mining, timber, fossil fuels, palm oil, rubber and fishing [1].

No comprehensive environmental education exists in the current national school curriculum although government documents make reference to such supposed programmes.

The public curriculum focuses on preparing school-goers for a life devoted to religious and commercial activity. As a result, the majority of students are left to believe that Indonesia’s natural environment is to be converted into profit.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change continues to highlight Indonesia’s deforestation as a kingpin in the global climate debate [6].

The Indonesian Government sits in the precarious position of facing scientific criticism of its environmental protection attitude while continuing to grow its economy by teaching its school-goers to focus on commerce.

The government’s largely dismissive reactions to international appeals to increase its biodiversity conservation efforts are creating mounting concern abroad and in Indonesia itself.

Statistics show how close Indonesia’s far-flung populations are to social calamity. When considered together, these indicators point to an alarming forecast:

· Unemployment ranks 61st in the world at approximately 6% [1], pressuring under-educated people into eking out a living by exploiting nature or migrating into urban areas.

· Deforestation adds considerably to the level of forest area shrinkage and land lost to soil erosion globally each year: 2,656,000 hectares / 3,575,000 hectares respectively were lost as of mid-2016 [7].

· Since the country’s major imports include machinery and fuels [1], items needed for the conversion of its environment are frequently within reach. This adds to the list of toxic chemicals being added to the environment worldwide each year: 5,002,000 as of mid-2016 [7].

· Indonesia is also the world’s 14th largest consumer of petroleum products, and is the 15th largest emitter of carbon dioxide from energy use [1].

Alastair wants to see such statistics turn to more encouraging ones in the near future, but to work out viable solutions one first needs to understand the issues clearly. Then pathways to solutions can be worked out. In all cases, it seems that environmental education is a cornerstone – as Al Gore’s office alluded to in a letter to Alastair in 2007.

In far-flung regions of the country which receive below-average government attention, including Papua in the east and Kalimantan (Indonesian Borneo) in the north, communities are largely left to fend for themselves financially. Locals, for example, who’re desperate for income, are selling plots of jungle to foreign or non-local businesses. Dubious mining activities pock the jungle. Kalimantan’s forest is also being clear-felled fast for conversion into high-profit palm oil plantations.

Far-flung communities have adopted extremely damaging environmental practices that are the diametric opposite of sustainable living. Such behaviours are now commonly “part of the culture”.

These forested islands, and other far-flung regions, are being decimated, both by environmentally ignorant locals and foreign entities backed by seemingly limitless financial resources.

Various socio-environmental forces are quickly converging into an imminent social disaster. The population is rapidly increasing and wasteful development behaviours are everywhere to be seen. Ecosystems across the country are in decline and natural resource overuse is the norm. This combination of factors is guaranteed to cause great misery for people in these areas unless they receive an appropriate education.

In central Kalimantan, for example, Alastair has met many 16-year old school boys who were unable to explain why trees exist. They also weren’t able to grasp simplified food chains or guess what happens to tons of plastic being discarded into jungle rivers. These same youth have access to chainsaws, fine-mesh fishing nets and shotguns which are in regular use.

Nevertheless, straightforward environmental education can change this social landscape for the better. That’s what really matters.

How can Have they told you? help?

Have they told you? - an initiative borne of concern for the people of Indonesia, aims to offer children in rural Indonesia the environmental education they’re not getting from the current government school curriculum. The project title was chosen because of its obvious answer. Almost all children in far-flung Indonesia have never received any environmental education; they simply haven’t been told.

Have they told you? offers long-lasting educational value which complements the existing government school curriculum:

· Lessons teach English alongside the national Bahasa Indonesia language content. It’s vital for Indonesian youth to speak an international language if they’re to keep their newly found awareness of global change up to date.

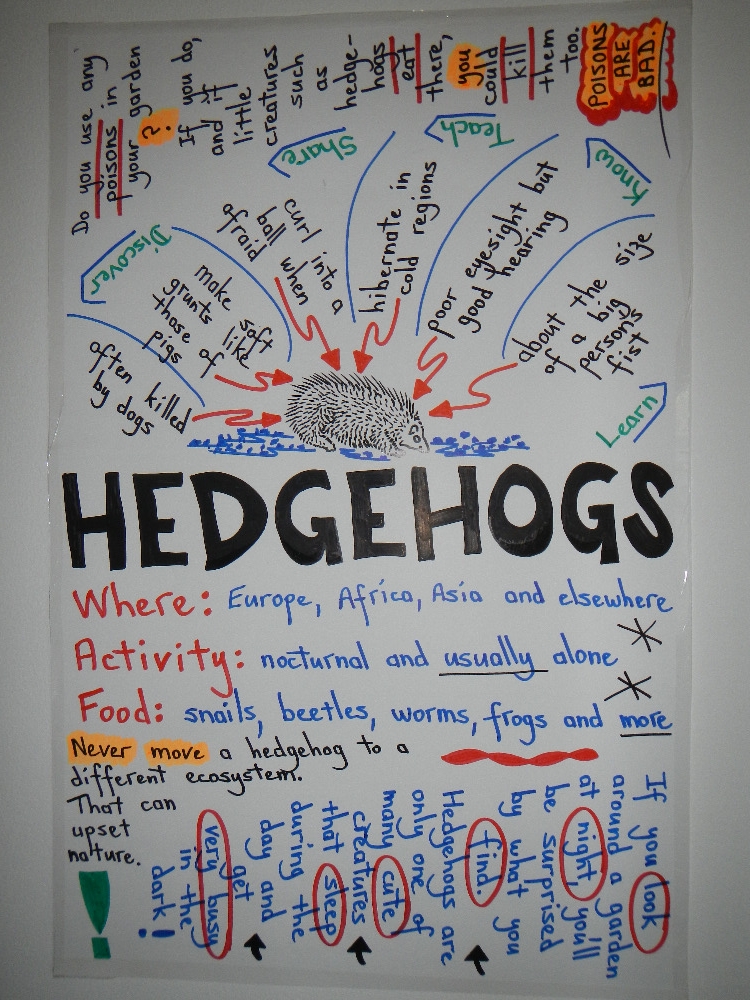

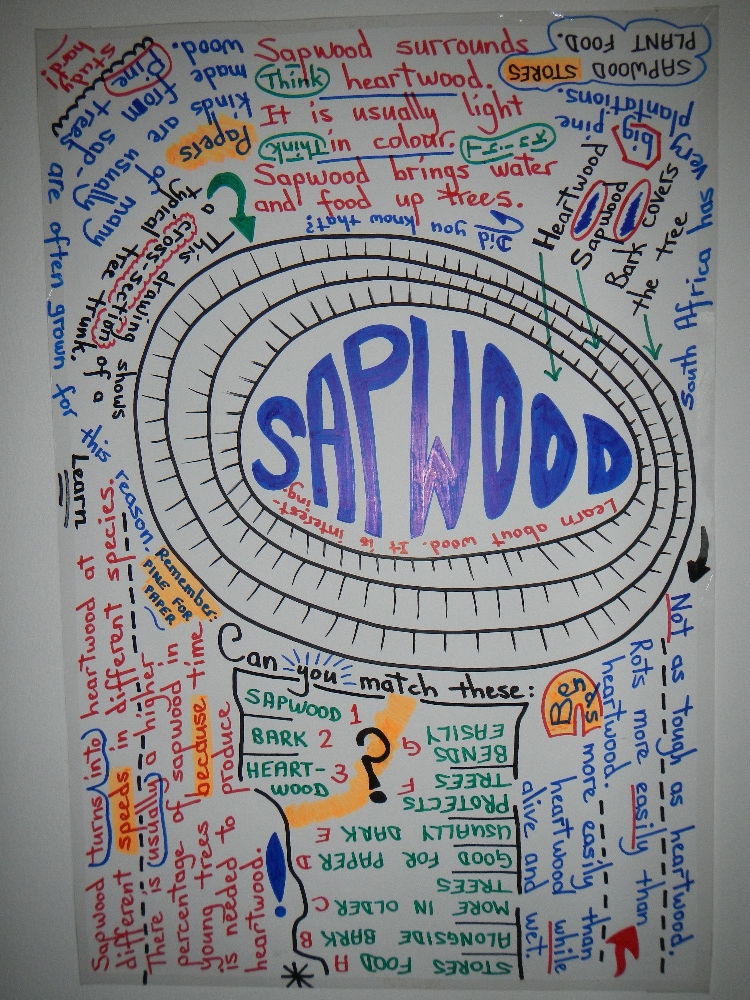

· Lessons aim to broaden the children’s general understanding of nature. They include a lot of data about the usual topics of biology, meteorology, hydrology, chemistry, geology, dendrology, ornithology, botany and entomology.

· All major environmental science categories are covered, some in detail. These range from the pleasantly informative and heartwarming to the cruel, worrisome and little-discussed. Planned obsolescence, mutual grooming, vivisection, snowflakes, resource wars, lobster migrations, the end of cheap oil, parental care, baby animal names, supervolcanoes, the seasons, overpopulation and much more are explained to introduce the students to what’s going on around them.

· Lessons include an active human focus. People are a part of natural systems, not independent of them. It’s imperative that children – especially among the 11% of Indonesians living below the poverty line [1] – are taught how improving their communities’ lifestyles in appropriate ways has positive impacts on the natural environment. Therefore, Alastair is developing lessons on the importance of regular exercise, the risks associated with smoking, the dangers of noise pollution, curbing sugar and salt intake, the dangers of fried foods, the benefits of infrastructure maintenance and the importance of reading.

· Potable water is a theme in many lessons. Since 24% of rural Indonesians don’t have access to sufficient drinking water [1], there is also considerable effort being put into teaching water-related issues.

· A large lesson on communicating with confidence is included. This shows children how to interact with each other well, and helps build their confidence for dealing with issues and with others in the future.

· Lessons on empowering women are included. It is hoped these will translate into meaningful relevant social change so that women – on equal standing with men – can make choices about their natural surrounds. In particular, these lessons explain that women should be respected and educated as much as men. This is important to allow them and their children free choices based on sound environmental education.

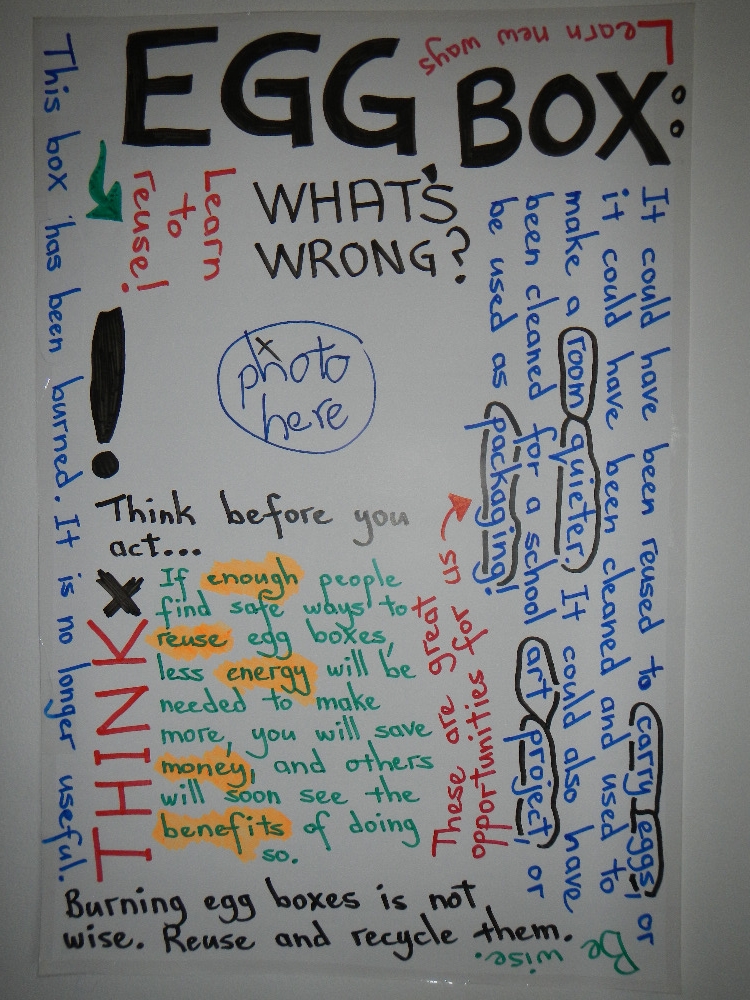

· There are also plenty of lessons related to sustainable community issues. These include how to make human-powered vehicles, how to separate and recycle garbage, how to identify and assign organic waste for maximum gains, trends in demographics and more.

Alastair knows there’s a lot more that can be added to the existing list of topics; things he’s not aware of. Please see the ‘rewards’ section for how you can contribute even more content.

How will Have they told you? be phased in?

The three project phases being carried out simultaneously are (i) attending to administration / digital work, (ii) creating the educational items, and (iii) collecting content on field trips.

Administration is being undertaken from Indonesia, the UK and the USA. Digital work is being done in Banjarmasin, Kalimantan, and UK-based input will soon begin. Legal matters will be attended to from Indonesia and the UK. The educational items are being made in and around Banjarmasin.

Supplementary information, thousands of explanatory photos and hundreds of video clips are being collected on low-budget field trips. Aside from localised day outings, the first four of these trips have been conducted in Indonesia and Singapore, with a fifth being planned for Thailand-Cambodia and the sixth in Papua New Guinea-Solomon Islands. During these expeditions (except for the first two), each to a different destination, information which can’t be found in Indonesia is gathered and then processed in Banjarmasin. This includes audio tracks and more. Networking during these trips has already lead the team to otherwise unobtainable interviews and case studies, helped widen the educational potential of the project, and assisted with fundraising.

Why can’t existing multimedia be used?

The team has reviewed the advantages and disadvantages of licensing multimedia content for this project. Undertaking periodic purpose-made international field trips is cheaper, easier and faster than using the intellectual property owned by others.

Doing so is cheaper because:

· No costly royalties need to be paid in hard currency, thus freeing up funds for shoestring-budget investigative travel;

· No job position needs to be created for someone to implement strict licensing agreement conditions with dozens of content owners in different countries while the project evolves.

Doing so is easier because:

· No time needs to be spent searching online for thousands of specific content files;

· The exact content desired can be created in situ, including interview clips on specific topics that are particular to Indonesia and will help engage the children;

· WorldRecordChase.com won’t be beholden to licensors should illegal copies of the educational items be distributed (disregard for intellectual property is rife in Indonesia).

Doing so is faster because:

· No difficulties waiting for content licensors to authorise or review agreements / content usage periodically is necessary.

How will Have they told you? be promoted to media and schools across Indonesia?

To bring the project to life and attract media, the team’s attempting a world record with Record Holders’ Republic. The challenge title is “Largest collection of hand-made educational items”. The team’s first goal is a compilation of 1,001 written, video and other types of lessons since this is an auspicious number in Indonesia. Thereafter, sequels of 1,001 lessons will be created for as long as funding and the regulatory environment allow - or until there are no more topics to cover. You can help the team get there!

It’s important that Alastair’s behaviour sets a practical example when possible because children watch and learn. One way he’s doing that is by planting trees. Reforesting ecologically damaged sites on the outskirts of villages in south and central Kalimantan with indigenous species began in November 2015. Forest cover is being extended to mimic the existing vegetation; it is not being replaced with plantation-style planted rows. This is being done in collaboration with schools and is Alastair’s contribution to offsetting carbon emissions created by travel. It would be wonderful if the children went away to plant their own native trees carefully, particularly on eroded land. Alastair also sells indigenous seedlings he grows in a tiny nursery constructed entirely from garbage.

The ultimate aim is to compile all written, video and other forms of lessons into ebooks - 1,001 lessons at a time, in small file size. These will be made downloadable for children and teachers, despite Indonesia’s notoriously problematic internet connectivity.

Each written lesson will appear as a page showing the English, with a simplified Bahasa language version opposite it. Video lessons and other lesson forms (including those on demonstrations of models) will be explained in the ebooks, with links to where they can be downloaded in both languages.

The publications will be marketed in Indonesia’s poorly developed rural areas, but anybody – including inquisitive adults and teachers wanting to expand their general knowledge - will be welcome to download them.

Creating thousands of these lessons will result in cubic metres of educational materials. To meet the world record attempt guidelines, these need to be displayed publicly (at a time to be decided on). That provides an excellent opportunity for the team to showcase the works made up to that stage. After that, it would make sense to move all the educational items into a large premises where the continuously expanding collection can be displayed long-term in the form of an environmental education centre. If this happens, centre management may decide to allow free entry for some, to make environmental education more accessible to the poorest children.

Environmental education isn’t an option if Indonesians (and the rest of humanity) want a great future – it’s imperative. Please support this team.

Questions and answers

Q1.

Is Indonesia’s lack of environmental education in government schools really a worry?

Definitely. As well as being inundated by plastic waste, the country’s current environmental issues include deforestation, water pollution, sewage contamination and air pollution at the same time as its population’s increasing by 2.4 million people annually [1].

Q2.

Why not leave the job of educating to the Indonesian Government?

Many international organisations are working hard to educate the lower rungs of society worldwide. This is a priority for the United Nations and others who understand that without good education, civilisation doesn’t have a bright future. Given that about 3.3% of Indonesia’s GDP is spent on education, which ranks it 143rd worldwide [1], if the team can help with this, why wouldn’t they?

Although situations change, this article by Elizabeth Pisani provides a startling insight into the basic mechanics of Indonesia’s government education system.

Q3.

Why should I be concerned?

Inequality’s a major factor contributing to environmental destruction everywhere. If the wealthier half of the global population devoted a measureable part of their lives to giving and sharing with the poorer half without taking back, the vast majority of social and environmental afflictions would be drastically reduced. In other words, to care is to be proactive. Moreover, Alastair encourages you to act because what happens in one ecosystem’s been proven to affect life in other ecosystems. And your life – like everyone else’s – depends solely on the capacity of ecosystems to keep you here.

Q4.

Why does this project need funding?

At present, Alastair and Nila are giving from their own money, which is limited, to this project. They’ve put in Indonesian rupiah 63,187,836 (USD 5,266) so far - as of mid-2016 - which is worth roughly 10 times this figure in developed nations. They intend to keep propping it up until it’s self-supporting if they can. But developing thousands of educational lessons for one of the largest school-going populations in the world is simply beyond the financial means of two individuals.

Exchange rates have been calculated using these averages: 1 USD = 12,000 Indonesian rupiah and 1 GBP = 18,000 Indonesian rupiah.

Q5.

What country is WorldRecordChase.com based in?

It started in New Zealand. The team’s been involved in many world record projects, and WorldRecordChase.com has attracted media exposure in places like Times Square and Milan.

Q6.

Who’s on this team?

Alastair Galpin (the New Zealander behind the project – www.WorldRecordChase.com / double zero six four 9 889 seven 909 / double zero six two 81 216 six 14 884), Rich Mellor (the UK agent – www.internetbusinessangels.com), Nila Adha (the team’s local administrator – [email redacted] / double zero six two 81 348 four 07 772) and John-Clark Levin (the team’s consultant in the USA - www.johnclarklevin.com / double zero one 805 746 five 798) form the central team. They draw on a wide range of expertise as required, encompassing many dozens of individuals and entities.

Q7.

Is WorldRecordChase.com a registered charity, and where can I find the details?

No, it’s private; Alastair is a sole trader. www.WorldRecordChase.com gives a comprehensive overview of what he and his ad hoc team do. Accounting advice Nila has received for this project is to use a separate bank account until the level of donations rises to a substantial figure, and then set up a legal Indonesian entity known as a foundation. By law, substantial costs need to be spent on administering the foundation. Indonesian Government data on the associated tax obligations can be found here, point #1 under the section “Tidak Termasuk Objek Pajak”.

Q8.

Who does your accounting, and how frequently are you audited?

The project has no accountant at this stage, although accounting advice has been sought in Banjarmasin. Alastair maintains a simple accounting book and keeps receipts when possible (but in Indonesia, a lot of transactions are done without paperwork). Not being a professional bookkeeper, it is possible his accounting contains minor errors. As the project gains impetus and funding, an accountant will be sought and engaged although the books are too simple to require such services yet. Currently Nila is responsible for overseeing all Indonesian financial and taxation matters regarding this project.

Q9.

Why not set up a complex, top-heavy business structure to operate under?

Life’s complex enough so the team prefers to keep things simple where they can. They see no point in spending money administering a time-consuming business model at this stage when their existing straightforward approach works satisfactorily. However, experts such as registered accountants will be consulted where required, including when it’s time to set up a legal Indonesian entity for this project called a foundation.

Q10.

Do you have a disclaimer?

Yes. The team’s trying their best within the constraints affecting them. These include time-related, financial, technology-related, culturally-related, religious and regulatory. For example, Alastair has no understanding of Indonesia’s financial and taxation laws, and is relying on Nila and other Indonesians to take care of all matters related to these. It’s entirely possible that mistakes may be made with any aspect of the project, and the team will try to mitigate these wherever possible.

Q11.

Why did you choose to align with Record Holders’ Republic for this?

Alastair approached numerous world record authorities with this project idea. RHR was chosen because it’s famous in Indonesia, made so by the phenomenally popular World Record show presented by celebrity Deddy Corbuzier on Trans TV in 2011.

Q12.

Will this likely come to fruition?

While risks will almost certainly be ever-present for such undertakings, enough progress has been made to show that this is gaining traction. Approximately 38kg of educational materials (480 items) have been made to date using 230 tubes of super glue, 670 good photos have been chosen, and field trip flight tickets have been booked months ahead. Another 130 items are being worked on. (Progress has slowed temporarily because Alastair’s spent months producing this fundraising campaign’s content, and he and Nila have been preparing a large project workshop area). Dozens more people are involved and more have offered help. A well-established author has expressed interest, media personnel are watching, and at least two international agencies are enthusiastic about what they’ve been told. For more, please see the campaign’s letters of support - 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6.

Q13.

Is there a website where I can find more detail and verify your activities?

Yes, at www.WorldRecordChase.com you can read about all WorldRecordChase.com’s activity over the past 13 years. This project’s not listed there yet because Alastair prefers to do things and then make them public. There’s a big difference between saying you’ll do something and having done it. In time, though, this project will appear on the website. In the meantime, limited information is being published at www.WorldRecordChaseBlog.com together with Alastair’s other world record-related news.

Q14.

Why haven’t you made your Indonesian physical address public in this campaign?

There are powerful business interests in Indonesia and abroad heavily opposed to this type of project because they know that environmental education adds to individuals’ freedom of choice. This appears to be a factor affecting all conservation groups in Indonesia. Bearing in mind that any address would be residential, Alastair and Nila felt it safer not to publish the project’s address in the interests of their safety. This is in line with other environmental groups’ policies.

Q15.

Aren’t there enough competing products?

There are many environmental education options on the market. However, most are costly, produced in foreign languages, or can’t be accessed online or in hard copy in remote Indonesian areas. Importing such resources attracts vast Customs duties, making that option prohibitive.

Q16.

Why not just buy books?

Indonesia is comprised of thousands of islands, some extremely remote and others integrated into mainstream society. Getting environmental education resources, or any teaching materials for that matter, into the more remote communities is difficult. If the team could find appropriately lively written English-cum-Bahasa materials, the challenge of distributing them would lie in logistics, care of packages in transit and in handling waste packaging. The associated costs would likely be very high because of the remoteness of many villages and the unforgiving terrain.

Yet, presuming that could all be done, undertaking this project as a world record attempt is expected to bring media interest which book distribution wouldn’t. Children take a natural interest in world records. Letting them know this project was done for them is a potentially powerful tool. By making students in remote areas (where regular book distribution usually doesn’t extend to) feel included, they’re more likely to want to explore what’s being offered. Their journeys of discovery should be newsworthy in themselves. It’s environmental education approached from another angle.

Q17.

How big an ecological footprint’s your team creating through this project?

Alastair worked out his current ecological footprint on an official UK-based calculator. Banjarmasin is very different, so the result of 2.5 [8] may need substantial adjusting. This figure is higher than the ideal of 1 for understandable reasons.

Recycling is nearly unheard of in rural Indonesia and is only rudimentarily implemented in many urban areas, so almost no good facilities exist. Alastair and Nila separate their waste but much of it gets dumped and / or burned whenever they aren’t present to oversee what happens to it. Many dietary basics are totally imported so buying some forms of nutrition means lots of food miles. To get around the congested sprawling cities here in 40 degree Celsius heat, motorbikes and scooters are the most efficient, but aren’t always the right items for the job at hand. Alastair wants the regular drivers to fit catalytic converters to their vehicles if these can be found. The drivers / vehicle renters may resist since anything unusual about vehicles attracts police attention.

This footprint size will change repeatedly during different phases of the project. For example, when on field trips, Alastair’s ecological footprint can fall to as low as 0.8 [8]. Hence, a footprint hasn’t been calculated for the entire team, the dynamics of which are constantly metamorphosing.

Q18.

Doesn’t your ecological footprint size make you a hypocrite?

Sustainability is a frowned-upon concept in much of Indonesia. Here, the majority of people are focused on making money. Sustainability-conscious people don’t find it easy. And that’s precisely why this project is being undertaken. Alastair and Nila face the dilemma of not being able to achieve their goals if they go “totally natural” while being aware that carrying out this project requires them to act unsustainably much of the time.

One tough hurdle is the social aspect. Alastair would love to reduce the project’s ecological footprint to 1, but achieving that would mean making enemies everywhere with those who think the necessary changes are obstructions. This applies both to people who’re part of the project and to those out in public, not to mention the additional cost involved. However, Alastair’s producing lessons as quickly as he can in the hopes that this generation of Indonesian children will read them, think about the information in them, and then change for the good of this earth. It’s better than creating a similarly sized ecological footprint by living a self-centred life.

Q19.

I’m offended that your core team gets paid – why don’t you all volunteer?

Most of the team is usually involved in paid work independently, making it unfair to request that they give up their incomes totally or in part to volunteer. Any project can’t be ongoing based on volunteers alone as people still have lives to live, families to care for and homes to rent. This project is Alastair’s primary engagement and therefore needs to provide him income.

Q20.

Is the team Muslim?

Some are. Others are Christian or have no faith.

Q21.

Is the team qualified to do this?

Yes, Alastair manages WorldRecordChase.com and takes part in all his own world record attempts. His background covers innovating, safety management system sales, writing, wildlife work and world record activities. Nila administers project matters from an Indonesian perspective. She’s an Australian-trained primary school teacher, and runs several entrepreneurial activities in Kalimantan. Rich is a software programmer with over 30 years’ experience in programming and e-commerce. John-Clark’s an entrepreneur active in international policy, media relations and project strategy. Anyone else asked to work with the team is, Alastair believes, right for the task. Please note that Alastair directs activities in good faith and trustingly takes responsibility for output produced by Rich, Nila and John-Clark during this project.

Q22.

Indonesia’s an Islamic state - does the team understand Muslim environmental views?

Not everybody on the team does. Alastair understands the basics and Nila, who provides advice on this subject, understands it in detail. Of relevance to this project is that Islam doesn’t permit natural resource wastage, and it denounces the polluting of urban and rural areas as a sin [9]. To help children follow their Islamic environmental teachings, alternatives to current environmentally destructive practices need to be provided. Hence lessons on suggested alternatives are being included. Scientific information is being followed, and Alastair isn’t adapting the truth to please people culturally and / or religiously.

Q23.

What are the team’s strengths and weaknesses?

The project relies on Alastair holding it together, with dedicated support from a core team. Major strengths include their track records, network of contacts and combined determination. Major weaknesses include the team’s partial dependence on funding, Alastair’s directness which can offend, the risk of him facing injury / death on field trips, the potential loss of continued input from core team members, and the possibility of the regulatory environment negatively affecting progress.

Q24.

Why are you only focusing on five of the eight Millennium Development Goals?

Alastair’s main interest is in environmental issues and this embodies some, but not all, the MDGs. This dovetails with two of the Indonesian Government’s current issues, being improving education and addressing climate change [1]. He believes those passionate about the remaining three MDGs should be left to educate about them, since they’ll have a much greater understanding of them.

Q25.

Why educate about nature when so many people are suffering?

Teaching people to overcome nature at any cost for their own advancement is a long-outdated approach. Many governments, while using public funds with determination and failing, have learned that forcing nature doesn’t work. Those that haven’t yet soon will, because the global population’s increasing by about 80 million every year [10], and it’s common for people to tend to destroy nature unless they’re educated otherwise. It’s now widely understood that to solve many types of social crises, degraded natural environments must be repaired first. WorldRecordChase.com is thinking ahead by teaching children to protect nature so that things don’t get that bad. You can help.

Q26.

What’s motivating you to do this?

Alastair’s primary motivation is wanting to throw some goodness out into this world that’s so scarred by negativity, using his world record-related abilities. The team’s informed enough to be able to help lead children through education, and they’re applying their knowledge. Alastair’s and the team’s secondary motivation is ensuring that they earn reasonable income via a guilt-free and deeply beneficial method, which Alastair believes this project offers.

Q27.

Surely things aren’t that bad for Indonesia’s environment, are they?

Alastair and Nila have personally seen many rifles, large chainsaws and innumerable fine-mesh fishing nets being sold openly in towns, and it’s easy to buy agricultural chemicals. Tree-cutters are usually armed, and have been known to shoot “problematic people” trying to stop them. A bonanza of land sales is leaving forests pocked with damaging activities, destructive industrial interests engage mercenaries to maintain the status quo, and some electoral candidates are using promises of increasing mining opportunities as a lure in their campaigns. There are, however, lots of excellent initiatives spread throughout Indonesia working to change this trajectory, and Alastair has taken his team to join them.

Q28.

How can you be sure children and teachers will want the ebooks?

Alastair and Nila have seen some really encouraging signs. Teachers they’ve spoken to have pleaded with them to bring good quality environmental education resources to their schools, and several are trying to teach related subjects out of personal concern for their surroundings. Many of the children Alastair and Nila have given environmental education classes to have listened, and gone home to tell their parents what they’d discovered. Besides being a fantastic result, this is deeply motivating.

Q29.

Will this be compulsory in Indonesian schools?

Ideally, yes. But for this education to be deemed compulsory in the public education system requires authorisation from the central government. Such permission, the team knows, will be exceedingly difficult to obtain because environmental education is largely viewed as a hurdle to economic development. It is far more likely the lessons will be made available as a voluntary extra, promoted actively wherever possible. Should the chance arise for this project to become compulsory in government schools, it will be done.

Q30.

How confident are you that people will be able to download these ebooks if internet signal is poor in rural Indonesia?

The project’s software engineers will be tasked with reducing the total file sizes to their absolute minimum without detracting from the ebooks’ readability. There are just over 42 million internet users [1] in the country, and that figure’s growing. Since BlackBerry phones and the like are so popular, the team’s confident that interested individuals will download the materials. Alastair and Nila will encourage teachers to download the ebooks in bulk on behalf of those without internet access.

Q31.

Do you have a finalised marketing plan?

Not yet. The team knows that to reach the target audience – children, their parents and teachers who have very little environmental knowledge or who aren’t even aware environmental issues exist, dedicated and specialised marketing will be necessary. The ebooks need to reach children in communities that have regular contact with the outside world, as well as in places where the government’s own education system has difficulty penetrating.

One good option may be collaborating with the major TV networks because even remotely situated families typically have TVs they watch a lot of. The team hopes to find decision-makers in big national media who’re prepared to forego the potential air time revenues in order to promote vital environmental education. Another good option includes working closely with Islamic leaders (imams), since they hold elevated positions of authority in society here. Alastair and Nila have spoken to imams in Kalimantan who know very well that thorough environmental education in schools is sorely needed. This is also very encouraging.

Further options are to engage actively on social media and to use word-of-mouth as a form of peer pressure. But above all, if the team’s efforts translate into legislature being passed that makes comprehensive environmental education compulsory in all Indonesian schools, with comprehensive implementation starting now, it’d be a victory of the greatest order.

Q32.

Will the ebooks be printable?

Yes, but the team hasn’t decided whether or not to allow multiple print-outs of each download instance.

Q33.

When did this project start?

February 2015.

Q34.

What are the project time frames?

It’s open-ended. Ideally, Alastair and Nila would like to keep the project running for years, stage by stage. The publication of each ebook containing 1,001 lessons marks the completion of each stage.

Q35.

Will you tell donors when the ebooks are published?

Not yet. So many facets of this project are evolving that the team simply can’t give accurate publication dates. What’s more, Alastair and Nila hope to release ebooks years into the future as situations and funding allow, whether this campaign exists then or not. But please feel free to enquire via www.WorldRecordChase.com or by calling.

Q36.

What guarantees exist to ensure this project will reach its long-term goals?

As much as Alastair would like to offer some, there aren’t any. Firstly, factors that’ll definitely end this project immediately include not having enough available money to continue, the death, illness or incapacity of team members, financial loss, or the Indonesian Government issuing an order for the team to stop altogether (in such a case, Alastair will attempt to translocate the project to another suitable country).

There are cases in which this government blocks online content from being accessed in Indonesia. Should this hurdle appear for Have they told you?, preventing its legal distribution throughout Indonesia, the team will do their best to distribute the materials (appropriately translated) in other countries that are sorely in need of environmental education.

Provided donations keep coming in, all the above hazards are unlikely, meaning Alastair believes the team’s chances of success are high. Secondly, attempting a world record provides no guarantees of success. But WorldRecordChase.com’s track record clearly shows how the team’s pushed through some lofty hurdles in the past, and stands ready to do so again if necessary.

Q37.

What information sources do you use?

Alastair’s childhood was spent playing, hiking, bird-watching, camping, fishing and working in the wild places of southern Africa. He studied environmental-oriented disciplines in South Africa and New Zealand, has backpacked through many developed and developing nations, and has independently informed himself broadly on issues related to environmental collapse globally. He remains interested in the clockwork-like demise of nature around the world and speaks out openly. This background, together with free publicly available information from well-respected credible entities and suggestions from others, forms the basis of the educational content being produced.

Q38.

Are you one of those tree-huggers?

Alastair is. Scientific literature points to certain socio-environmental collapse in the near-term unless drastic corrective changes are made immediately across all of society. Nothing substantial enough is being done, while simultaneously, the rate of environmental destruction’s accelerating. Although it may read somewhat tactlessly, Alastair’s opinion is that those who aren’t deeply concerned need to be informed as much as this project’s target audience does.

Q39.

Who actually makes the written lessons and takes the raw video footage?

Alastair does, sometimes with help. He’s also started creating other forms of lessons, including several songs and poems with appropriate lyrics.

Q40.

What materials do you use to create these lessons?

About 75% of all items used to create the written lessons are from cleaned and suitably prepared garbage, used paper products and the like. Alastair’s doing this to show children that much garbage is useful but hasn’t yet been applied to new uses. The remaining 25% is newly bought products because he needs glue, ink, wire, transparent tape and so forth.

Q41.

How’s the content of these educational items decided?

For anyone interested in environmental issues, it’s not hard deciding what to teach children who stare blankly when asked what they know about nature!

Q42.

Why teach environmental concepts from other countries if this project’s for Indonesian children?

Natural systems function interconnected, irrelevant of man-made boundaries. Teaching only chunks of environmental education will leave gaps in children’s knowledge. The team aims to deliver a comprehensive suite of environmental education topics. For instance, ecosystem changes in Borneo and Greenland depict opposite ends of the same climate change story. But due to cultural and religious sensitivities, some topics may not be directly taught in Indonesia. With guidance, Alastair is tactfully teaching these by indirect means.

Q43.

Your lessons aren’t very professionally made – why?

Alastair’s conducting this project on as little money as he needs to spend, while not compromising on educational integrity. Applicable, abundant, high-quality, affordable turnkey teaching resources simply aren’t readily available here. Even if they were, buying them would mean the team’s ecological footprint would expand multiple times over. In addition, hand-made lessons made from trashed items can be filled with character since Alastair has the freedom to be creative as needed, and children like that.

Q44.

How long does it take to produce one lesson?

Getting permission for and collecting items to include in the lessons, including walking streets or open spaces, can take Alastair anything from hours to weeks. Field trip preparations, including making CouchSurfing enquiries and expedition preparations, is time-consuming too. Sometimes arrangements for filming interesting things have to be made months in advance. Researching and preparing content at the project base often takes several hours but can also take just a few minutes, depending on how long Alastair’s got to think for. Writing each lesson is relatively quick at an average of an hour. Once done, photos and artefacts need to be created and / or attached, and the lessons need to be tidied up. Video lessons and other lesson types mostly take weeks to be finalised.

Q45.

Does the team do this full-time?

No. For each project WorldRecordChase.com takes on, Alastair draws on an ad hoc team whose backgrounds are diverse. Members of the team – and others called on - normally work in innovation, law, health and safety, marketing, education, e-commerce and web design. But Alastair’s involved in planning and undertaking multiple world record attempts and other such activities full-time. This project’s his focus, although all those involved have other things going on simultaneously.

Q46.

How do I know you’re not claiming costs unrelated to this project?

Alastair spends most of his time on this project, but attends to other matters as they arise. He’s taking steps to compensate for erratic downtime on this project. These include wanting to draw only Indonesian rupiah 360,000 (USD 30) as a daily wage for up to 10 hours’ effort which is far below New Zealand’s legal minimum wage, contributing financially until this project becomes self-supporting if he can, and not including expenses that can’t reasonably be linked to this project by an enquiring independent third party.

Q47.

Who’ll decide what lessons are for which age groups?

The team doesn’t know yet. Alastair’s aim is to provide as much environmental education as possible, but understands that all lessons can’t be given to all children together. He and Nila are seeking professional advice to help arrange the educational content appropriately.

Q48.

If the target children’s level of education is so low, will they understand your lessons?

Alastair and Nila believe so because 94% of the population over 15 years can read and write [1]. Students will need lots of help from teachers to understand the lessons, which is to be anticipated during steep learning curves. Alastair and Nila expect that children will find the English lessons a great challenge which is why basic Bahasa language translations will be provided, although they strongly encourage the children to try reading and understanding it. Whatever English the students learn will help them for life.

Q49.

Will the information be reviewed by suitably knowledgeable professionals?

Yes, Alastair’s looking. He and Nila have been offered contact points for education professionals in Australia but continue to seek highly knowledgeable professionals who can quickly assess the accuracy and level of bias in all lessons. Changes and corrections will be made as needed, although pro-nature conservation bias won’t be removed.

Q50.

Has the Indonesian Government shown interest?

One month into the project, an Indonesian teacher and Alastair went to introduce it to the Minister of Education in a remote area of central Kalimantan. They were ushered out of the Minister’s office by his secretary; the team hopes for positive interest from the national education department in the near future. Informally, another department of the Indonesian Government’s expressed interest but is waiting to see the team’s progress before further considering support.

Q51.

Will the ebooks have ISBNs?

No. Buying ISBNs is expensive and this is seen as a waste of money that could otherwise be put into the project.

Q52.

What about intellectual property?

All intellectual property incorporated in this project belongs to WorldRecordChase.com, except where such claims cannot be made under law. At any time, the team may choose to give away some or all of this intellectual property if they decide it’d be for the greater good. Equally, they may license or sell it if entities who’re genuinely concerned about environmental issues are interested.

If you’re wondering about licensing these ebooks or translations of them for another country, please speak to us! The same pro-education, low-profit attitude the team’s applying in Indonesia will apply to every other country where such important educational content isn’t reaching children.

Q53.

How will you react if fake copies of your ebooks are made?

Sadly, there’s a high chance of this happening in southeast Asia particularly, and Alastair’s prepared for copyright infringement. While the team won’t approve of it, they’ll likely take no action if unedited / unmodified fakes are being distributed free of charge to children who need environmental education badly. But if attempts are made to profit from distributing parts of or whole fake copies of the ebooks, legal action will ensue to the full extent of the law. The team won’t tolerate illicit profiteering from a resource they created to be widely distributed at pitifully low cost to those who need to know most. But hopefully everything will be fine.

Q54.

When will project updates be posted?

Alastair doesn’t plan to provide updates on a regular basis, but rather whenever the team has something worth sharing. This could mean posting nothing for months or many updates in a week, for example.

Q55.

Can I come and check what you’re doing, or volunteer?

Yes certainly, that would be great – provided doing so is legal under Indonesian law. If you’re lucky, Alastair and Nila might be able to pay you for your contribution. They would prefer not to be tripping over a constant stream of “checkers” though.

Please note they’re following a project plan, so not all volunteers’ ideas will fit. Whatever lessons are created need to be of a high standard, and physical items must be robust so they withstand manhandling as well as wear and tear.

The easiest type of volunteering to allow is “helping out” with menial tasks. For instance, these could be taping the edges of piles of used paper / visiting language classes to speak about nature / gluing simple demonstrative items together, while more advanced voluntary input requires planning and discussion.

Alastair works alone most (but not all) of the time because finding a full-time on-site assistant has proven to be an unsuccessful challenge. He researches, designs and produces lessons, collects and sanitises components, constructs his own experiments, manages photo and video content, attends to enquiries, liaises with other sustainability initiatives and runs the on-site administration. Nila helps wherever she can and Rich and John-Clark are constantly on standby. A helping hand with some of these tasks at times would be good.

Alastair is also the cleaner for this project. Finding cleaners with appropriate know-how is difficult here, and much of his time could be spent more productively if he had someone to clean up the paper mache work area, garbage washing bay, tools, walkways, work clothes and more. So, if you’re a professional domestic cleaner, your skills will be valuable if you choose to help in this way!

More complex tasks are the likes of making a temporary wind tunnel only from discarded plastic sheeting, designing a hand-written flow chart of all grades of plastic for recycling purposes on the back of a discarded plastic door, or making and modelling paper mache into demonstrative items like flexing spinal columns by using simple tools and waste. In addition, expert checks of lessons’ factual content, professional English-Bahasa translations of written lessons and the comprehensive photographing of almost all types of content pre-publication will be needed in time. These require a person being on site.

Note: Alastair is very clean and extremely organised when at the project base. If you’re a smoker, don’t wash your body properly, tend to leave cleaning jobs for someone else, are generally untidy / disorganised / live an unmaintained lifestyle or are otherwise of low standards you won’t be welcome.

Have they told you? will not expect anybody to pay a fee for the privilege of volunteering. Alastair and Nila realise that by volunteering, a person is already making sacrifices. Visitors are fed and taken care of as is a normal part of hospitality, but you will need to get yourself here at your own cost.

If you want to help over the internet, that might also be possible. Alastair will soon need someone (or several people) to turn his educational lyrics into songs. These must be “cool” so children want to listen to them over and over again. Other jobs such as enhancing sound recordings will be needed in time too.

All intellectual property incorporated in this project by volunteers and paid contributors alike belongs to WorldRecordChase.com, except where such claims cannot be made under law. This is normally agreed upon by email or on video. This is because, as the project advances, it is likely that Alastair will need to prove the project’s intellectual property rights situation to management-level collaborators. An unclear / unconsolidated intellectual property portfolio is always a good reason for project backers to withdraw.

Q56.

How have you funded the project to date?

Alastair and Nila have been using their own money. Minor donations have also been received, and separated domestic garbage has been sold to a waste recycler for IDR 112,000 (less than USD 10) as of mid-2016. Alastair and Nila also donate to other causes independently of this project, and although noble, can’t sustain the giving without receiving funds.

Exchange rates have been calculated using these averages: 1 USD = 12,000 Indonesian rupiah and 1 GBP = 18,000 Indonesian rupiah.

Q57.

What are your overhead costs like?

Together with marketing and field trip costs, software-related work is vital to keep the project running online long-term. It’s anticipated that almost all marketing will be done from in Indonesia. Field trips are being saved towards weekly throughout the year and surpluses after trips typically remain in the project budget.

From donations, Rich will receive a maximum of 30% gross. This covers costs in connection with the provision of advice relating to legal matters, plus contractual and campaign issues. It also includes ongoing programming and software maintenance, the upkeep of relevant parts of WorldRecordChase.com, as well as costs associated with administering payments and remitting them to Alastair’s project bank account - including banking of donations and international payment fees. In addition, Rich manages issues that arise while Alastair’s on field trips.

These services, and possibly more such, are needed (two ‘best estimates’ - 1 and 2 - of possible ideal budgets have been included with this campaign). Alastair’s chosen to pay those who’ve proven trustworthy, and have been with WorldRecordChase.com for many years. Among other regular costs is Alastair’s nutrition, although this is minimal and may not always be claimed. Please note that these estimates include some costed activities which are currently being postponed due to insufficient finance.

Q58.

What happens to these overheads during your field trips?

Some stop altogether and others drop substantially. The two possible budget ‘best estimates’ - 1 and 2 - included with this campaign reflect costs as they arise. So when Alastair’s on field trips (sometimes with Nila), many stop because he’s not producing lessons which require those services at the time. These include photo printing, basic video editing, food gifts for local team members, local helpers’ wages, a translation service and a professional photographer. Costs that decrease include bank fees, food and drink at base and transport. Please note these are generalisations and are constantly influenced as the team progresses.

Q59.

What if you experience a cash flow crisis?

Two ‘best estimates’ - 1 and 2 - of possible budgets have been included with this campaign. You’ll see that at this stage, Alastair and Nila don’t have enough available funds to allocate to everything that’s needed. They may need to continue to postpone some professional services and saving towards future fee payments until sufficient funds allow those aspects of the project to proceed.

Q60.

What are the biggest costs you face right now?

Alastair needs one powerful laptop for processing project requirements (the old one will be disassembled and used in models). His second-hand GoPro will need replacing when it ceases to work properly. He also needs a 512 GB micro-SD card for storing project data.

He and Nila need money to pay for internet access, photo printing, basic video editing, team sustenance, help collecting unwanted items to make the lessons out of, phone calls and texts, additional disk space on the MyHost servers in New Zealand which host www.WorldRecordChase.com or a redirect, artisans to provide basic services, expert English-Bahasa Indonesia translations, a local professional photographer, xylene-free permanent markers, 9542A particulate respirator masks by 3M, a range of publishing-related services, general and Indonesia-specific legal advice, insurances as appropriate, e-commerce design, general software programming, international air / surface transport tickets, visas, and field trip sundries including access to places of interest.

This distribution of costs over 11 months gives a breakdown of this period’s expenditure as percentages.

Alastair admits there may be easier ways of doing some things, but it’s natural for people to want to continue using functional systems they’re familiar with (and he realises this attitude’s routinely discussed in sustainability debates).

Q61.

Isn’t asking for donations towards your field trips offensive?

It could be for some, but this is being asked because field excursions are an integral part of the project. Children from far-flung and / or insular communities with a low level of general knowledge need plenty of visuals to help them grasp concepts, and getting that’s the primary purpose of field trips. Please note that Alastair and Nila are supporting this project substantially with their own money and will only claim 50% of this back if the finances allow it in time.

Being cost-aware, Alastair uses CouchSurfing and other similar websites to lower his field trip costs, camps where it’s free to, sometimes walks up to 15km a day instead of paying for transport, eats mostly basic staples, doesn’t pay for leisure, routinely asks for free entry into places of interest, networks with locals to access what areas he can get to free or cheaply, uses a travel agent whose brief is to seek out the very cheapest transport options – despite inconveniences, and he bargains quid quo pro wherever appropriate. These field trips are akin to disciplined, spartan scouting or orienteering expeditions. Alastair typically carries only 5kg of essentials in hot climates and 8kg in colder ones, and “travels hard” so as to limit waste.

Q62.

Will your fundraising goal remain constant?

No. Alastair and Nila are confident that some needed goods and services will be offered free of charge. But the team has to pay for others managed by people who’re money-oriented, or by those who’re entitled to fair pay. As the project extends, the team knows there’ll be large costs in both hard and local currency. As these arise, the fundraising goal will change. Some big costs to come include the legal requirement to set up and administer a foundation, and, subject to possible reviews by Indonesian taxation professionals, paying tax on large donation totals. You can help this project stay afloat by donating more than once if you’re satisfied with the progress you see.

Q63.

Will I get a tax receipt?

Because WorldRecordChase.com isn’t a non-profit organisation, donors can’t claim their donations as tax deductions. GoFundMe has told Alastair that while not offering a guarantee, donations made here are considered ‘personal gifts’ which aren’t taxed as income specifically in the USA. Regulations in other countries may differ.

Q64.

Why are there so many bank fees involved in your project?

Alastair agrees – there are far too many bank fees. GoFundMe in the USA receives donations from anywhere worldwide. Then GoFundMe holds these donations, takes a cut, and their payment processor takes a fee which can vary according to country. GoFundMe won’t pay out donations to New Zealand or directly to Indonesia, so the donations have to be sent to the UK where Rich is based.

If it’s possible, legal and advisable, the donations can be sent from the UK to the project’s bank account in Indonesia. However, if, for any reason, this isn’t possible, the donations will need to be sent from the UK to Alastair’s account in New Zealand and then brought to Indonesia. Each of these stages will incur bank fees.

This long trail of bank fees is anything but pleasing to deal with, Alastair knows. Add to this fluctuating foreign exchange rates, and a noticeable percentage of the donations are ending up in bank coffers. Still, the team is doing what they can to strive for their project goals and educate.

Q65.

To help reduce bank fees, can I donate directly to you?

As far as the team’s concerned, they’re fine with that. But GoFundMe might prefer you donate here since they’re hosting this campaign. What’s more, the team may stand to benefit more in the long term if you donate here because of how crowdfunding works. The higher the published level of donations made on such websites, the more inspiring it becomes for others to follow and donate. In this way, the web of donors has the potential to expand almost infinitely, thereby providing the financial support such projects need. But if you choose to donate directly to the project offline, the team may add your contribution to the ‘amount raised’ figure published on this campaign.

Q66.

How much are you expecting to raise in donations offline?

The team doesn’t know. Anybody in any nation could offer support at any time, including via other online donation systems. Goods and services to the retail value of Indonesian rupiah 17,908,000 (USD 1,492) have been donated as of mid-2016 - these are verifiable amounts, and exclude favours and kind people’s time. The public donation box has raised Indonesian rupiah 1,596,300 (USD 133) as of mid-2016. Also, Alastair and Nila continuously contribute substantial sums to this project.

Exchange rates have been calculated using these averages: 1 USD = 12,000 Indonesian rupiah and 1 GBP = 18,000 Indonesian rupiah.

Due to fluctuating exchange rates between multiple currencies and items being donated with their price tags removed, there’s a chance the historical offline donations the team may publish on GoFundMe won’t be an accurate up-to-date reflection of what’s actually been contributed offline. Should you see a need to take a look through Alastair’s simple books for this project, please make an appointment to do so in person. If you wish to speak to the team about any Indonesian financial and taxation matters regarding the project at this time, please ask for Nila.

Q67.

Can I donate in other ways, without giving money?

Possibly, yes. Giving air points (air miles) is a great way to support this project. You could suggest a destination or the team can provide you with a list of upcoming field trip locations. Then you can use your air points to pay for Alastair’s transport there and / or back. Alastair strongly prefers to use ecologically-conscious companies if budgets allow, including surface transport as an alternative to flying. Another way you can help non-financially is by booking Alastair into an interesting field trip activity where you have appropriate contacts. He would arrive and undertake project research in the normal way.

Or you could ask what gear and supplies are needed and send those if permitted by law. Many things readily available in advanced nations cannot be bought here - especially if one is seeking quality. For instance, a small solar pack or wind turbine, a small freeze dryer, IFOAM certified organic seeds, small wildlife tracking devices, a sextant, a heavy metals test kit, a tiny air compressor, a tree bicycle, a small thermal imaging camera and other specialist items would allow Alastair to produce additional lessons more easily.

A further alternative is to assist with nutrition. Honestly labelled, low-sugar and low-salt, synthetic additive-free, pesticide-free, heavy metal-free, MSG-free, minimally processed foods that are produced to international food safety standards are very difficult to find in Indonesia. Formaldehyde, borax and fabric dyes are commonly injected into / applied to foods by roadside vendors, and mercury is released into rivers which supply informal river-side fish farms. PET plastic bottles are melted into repeatedly used frying oil to make foods crispier. Products that have been illegally mimicked in backyard set-ups are also both commonplace and tricky to identify.

Alastair and Nila live off a narrow variety of carefully chosen foods to avoid exposure to unregulated risks. Hence quality supplements from HealthForce and Raw Organic Whey would provide them with a more balanced diet. Certified organic molasses, yoghurt powder, fennel seeds, walnuts, carob powder, chia seeds, liquorice seeds, green tea and more would be a joy to taste too!

Companies such as USGoBuy act as delivery agents for items that would otherwise be immensely frustrating for expatriates to import.

Q68.

What if you don’t raise your funding target?

Then Alastair and Nila, and possibly others on the team, will personally fund the rest of the project or continue working without pay if further fundraising efforts produce no / insufficient funds. If these sources run out of funds the project will collapse. The team will then make the materials produced to date public, and Alastair will submit the world record attempt evidence and consider it done. From the public’s perspective, this will still look good – just not as big as the team’s aiming for.

Q69.

What if you raise more funding than your project needs?

When the project reaches its final stages and / or no longer needs funding, the team will do the responsible thing by closing this campaign and notifying offline donors. However, in the unlikely event that donations exceed project requirements, the surplus will go straight to Alastair and Rich who continue to pursue other world record projects, plus to Nila and others who’ve helped. Should a donations surplus arise, and should you object to it being kept as described, please raise this matter directly with Alastair and Nila who’ll be responsible for dealing with it.

Q70.

If this project fails, can I get my donation back?

No, because it’ll have been spent. Take heart though, because whatever materials are being produced will end up used in educating children about nature.

Q71.

Where else are you seeking funding?

Alastair and Rich have pitched to the companies whose products Alastair’s using the most. They may pitch to others too. However, since companies commonly seek maximum financial returns, the team understand that there’s likely to be limited corporate interest in supporting a project of this type. The team may also run campaigns with other online donation systems so if you browse a few of them, you may see this campaign again.

Where appropriate, outside of the crowdfunding arena, Alastair may cautiously advertise opportunities for companies to brand individual lessons. For a nominal direct payment, an activity or service of theirs will be showcased as a good example. The focus would be on attempting to associate specific brands with sustainable lifestyles. Overt background checks will be carried out and barriers to entry will be high to prevent business as usual gaining cheap advertising.

Q72.

How responsible have you been with past donations?

WorldRecordChase.com has received considerable sums of money from large companies / organisations in the Asia-Pacific region. All project funds, bar for one project, have been used appropriately and Alastair’s been offered successive funding by some donors. Sadly, one motoring-related project that started in 2006 failed due to incompatibility issues with road regulation standards in New Zealand. Monies spent on that project produced no results and the project was postponed indefinitely; Alastair continues to pitch this project to potential funders.

Q73.

Can you outline your project’s general money flow?

In general terms, yes. Nila’s accounting advice has been for Alastair to open an Indonesian bank account in his name initially, and to have a foundation set up at a later time. Maybank Indonesia was chosen. Donations being deposited include Alastair’s and Nila’s own money they’re using to support the project at this stage. Should people choose to donate in cash, such monies will either be kept as cash or be banked in the same account. An accounting record is being kept of cash donations kept in cash, cash donations Alastair and Nila bank, and donations made into the project bank account (including those originating on GoFundMe or other online donation systems, and from Alastair and Nila).

Except where there are reasons not to, all project costs are being taken out of this one account so that a clean financial record exists. Paper trails exist. The exception is Rich’s payments; these are taken before the GoFundMe donations arrive in the Indonesian bank account. Payments being made include those for goods and services of all sorts needed to keep the project running, including team member payments.

Q74.

How much money are you going to make?

As opportunities come and go during this project, aspects to the financials are likely to change. Once the finances are robust enough, Alastair and Nila want to start drawing a wage, backdated to 1 March 2015. For Alastair, this’ll be Indonesian rupiah 360,000 (USD 30) for every day. For Nila, this’ll be Indonesian rupiah 120,000 (USD 10) for every day. Alastair and Nila also wish to pay themselves out, in Indonesian rupiah, 50% of the total donations they’ve each made to the project, only once cash flow is sufficient and relatively stable. John-Clark’s paid USD 25 per hour for tasks as required. These unequal figures reflect wage expectations in Indonesia and the USA, although Alastair and John-Clark have voluntarily lowered the amount they could receive. Others are paid on a case-by-case basis.

At this stage, Alastair plans to profit personally by no more than 10 American cents per ebook of 1,001 lessons. Whatever happens, the profit margin on the ebooks won’t be increased beyond the purchasing power of the very poorest families. Alastair and Nila believe 10 American cents profit is acceptable for enough cool environmental education lessons to keep a child reading for a year – or maybe longer!

In the unlikely event that donations exceed project requirements, the surplus will go straight to Alastair and Rich who continue to pursue other world record projects, plus to Nila and others who’ve helped. Alastair considers all money he and Nila may make to be acceptable, considering their personal financial and non-financial contributions to the project.

Q75.

It seems you’ve designed this project for your own benefit – isn’t that correct?

To some extent, yes, but not entirely. Contributing willingly to positive socio-environmental change in an unfamiliar culture where millions are suspicious of foreigners’ motives is sometimes tough on the team. The vast majority of well-meaning foreigners who enthusiastically try these sorts of things give up in a short time due to such pressures and challenges. Alastair wants to be here for the long run.

While there are purely selfless ways of achieving the same educational outcomes, Alastair believes that he and the entire team are entitled to comforts as the project progresses. If people are content, it’ll reflect in their work ethic. Moreover, cutting out all luxuries will almost certainly cause the team to abandon the project, and that’d be far worse long-term than undertaking the project with comforts.

Q76.

Some of your world records are stupid – how do we know you can do this?

Many factors affect when and where Alastair’s able to undertake world record activities. Admittedly, some of his acts have been less than impressive while others have turned heads internationally. For example, anti-gambling groups in different parts of the world reacted enthusiastically to this, helping to spread the message carried by a lot of media. Made at the time of the Rugby World Cup 2011, this giant ball was sold to a famous sports museum. And this long handshake organised by a USA-based team, in which Alastair and his handshaking partner tied against the Nepalese team, became the third biggest online news story worldwide at the time.

Q77.

Some of your projects have failed – can donors trust you this time?

Alastair thinks so, yes. In most cases, WorldRecordChase.com’s failures can be directly traced to sponsorships and other funding sources running dry. The 2007-8 global financial crisis and its aftermath, for instance, had a substantial impact on his ability to run some projects. Where the necessary funds have been readily available, Alastair’s been able to prove his dedication to the projects he undertakes. Right now, he and Nila are putting money into this project as well as asking for donations here and elsewhere. If the money comes in, Alastair thinks this one’s destined to be a winner. And you can hold him to that statement.

Q78.

This all sounds very high risk, don’t you agree?

Yes, it’s high risk, and so have most of WorldRecordChase.com’s projects over the past 13 years been. The majority of these have succeeded. Importantly though, there’s a reason that more socio-environmental projects are undertaken in advanced nations. It’s certainly not easy to implement conservation-oriented change in countries suffering from extensive lists of stubborn problems. It’s far easier and faster to accomplish such goals in developed parts of the world, and that contributes to increasing the gap between developed and developing states.

Alastair’s investing his effort where he believes it’s most needed: in the developing world. He’s hopeful, but is constantly facing obstacles that are to be anticipated. These include complete indifference from people in various positions of authority, being ignored by offshore NGOs that are renowned for advertising their commitments to sustainable change, being rejected by many outfits approached for gear sponsorships, being turned away by academic facilities which house artefacts or undertakings of relevance, and facing criticism from individuals who believe this project is unnecessary. Electricity cuts, rat infestations, water shortages, theft by postal service workers, bouts of diarrhoea, constant postponements from third parties, flooding, the sporadic hazard of civil rioting and more are also slowing progress.

Yet, Alastair is facing these difficulties on sources of valued assistance, although they’re not guaranteed. He knows the direct and indirect setbacks are occurring largely due to ignorance in its many forms – this only makes him more determined to educate. The worst possible decision in this instance would be to leave a lot of Indonesian children with almost no environmental education while their country becomes increasingly infamous for destroying the natural world. The best decision would be for him to proceed. So, by building on the support available and by maintaining hope, here’s to environmental education for children in far-flung Indonesia!

*

Thankfully, there are continuously amusing moments. These are the best and worst face-to-face statements Alastair’s received since beginning the project:

· “We have that day off work. Both of us will spend it helping you in any way we can”.

· “We cannot support environmental education because that might cause political problems for our country”.

Alastair and his team can say a heartwarming “thank you” for your donation but that would never be good enough. Young people need to be taught to distance themselves from consumerism-driven society for the sake of life on earth. If this can be achieved in time, the “thank you!” their descendants shout will be infinitely more meaningful.

Just before you go: find Alastair on YouTube, and follow him on Facebook.

Reward levels

All contributors will be added to the project credits list, using the name they supply when donating (an ‘anonymous’ option exists here and offline donors can ask not to be named).

Donate anything from GBP 5 to GBP 19 and feel good. Hey, you could spend that on yourself. But if you do, you’ll just be adding to your own ecological footprint and no child would be any closer to understanding the amazing natural world that surrounds them.

Reward level 1.

Donate GBP 20 or more and Alastair will create one SMALL-sized lesson (typically 50cm x 40cm) on an appropriate topic you list, with recommendations, only if background checks find it to be a verifiable sustainable activity / it’s not already included. This can be about your own organisation or business.

Reward level 2.

Donate GBP 50 or more and Alastair will create two SMALL-sized lessons (typically 50cm x 40cm) on appropriate topics you list, with recommendations, only if background checks find them to be verifiable sustainable activities / they’re not already included. They can include your own organisation or business.

Reward level 3.

Donate GBP 100 or more and Alastair will create two MEDIUM-sized lessons (typically 70cm x 60cm) on appropriate topics you list, with recommendations, only if background checks find them to be verifiable sustainable activities / they’re not already included. They can include your own organisation or business.

Reward level 4.