Help Libby Leask

Donation protected

Article by Algernon D'Ammassa, Las Cruces Sun News

https://www.lcsun-news.com/

When Elizabeth "Libby" Leask, 61, listed her Las Cruces home for sale early in February, she described it as a surrender.

"I don't have anything else to give up," she said. "I can't afford to fight anymore."

Since the sudden death of her husband in 2016, Libby Leask has been seeking her late husband's pension. As a multiple sclerosis patient, she was counting on the income to take care of her for the remainder of her life, as her late husband had planned.

Yet after 27 months consulting with attorneys and appealing for help from New Mexico State University, her husband's employer, and the New Mexico Educational Retirement Board, Leask is selling her home and preparing to move out of state to live with family.

Despite her medical condition, she will need to return to her former occupation — painting houses — in order to live.

What kept her from collecting her husband's pension was a single missing form: Form 42, the official form designating her as her husband's beneficiary.

'You need that Form 42'

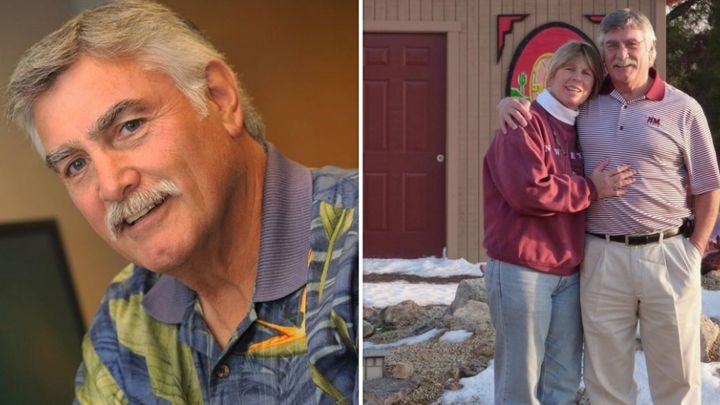

Steven Leask was 66 when he died on Nov. 1, 2016. He had been a helicopter pilot in Korea, Vietnam and Alaska with the U.S. Army, earned a Master's degree and doctorate from NMSU, and since 1997 had worked for the university in the Educational Administration department.

In 2017, a memorial fund for Native American or military veteran students was established at the university in his name.

Libby vividly recalled coping with legal formalities in the midst of trauma over her husband's sudden death. At the FedEx store on University Avenue, her hands shook so much she needed an employee to help straighten her papers and fax them to the Educational Retirement Board.

Initially, she said an ERB representative told her the death certificate was all they needed, but subsequently they requested more documents, including parts of her husband's will.

"And then it was, 'We're not sure you're the beneficiary,'" Leask said. "I finally faxed them the whole will, everything, and then they ran out of things for me to fax."

It came down to the missing Form 42. Without it, Leask could not prove she was the designated beneficiary of her husband's pension, even though they had been lawfully married since 1985.

Josh Dwyer, an attorney at the Scott Hulse law firm in Las Cruces specializing in estate planning, said Leask's predicament is all too common.

"The legal framework for how these things work is very foreign to people until they're thrust in the middle of it," Dwyer said. "There are different rules for different types of assets, probate assets that are controlled by the will and non-probate assets, like bank accounts."

ERB suggested Leask go through probate and set up an estate. A few months and about $4,000 later, the estate was established, but then ERB attorneys told her Steven Leask's will did not prove she was the beneficiary of his retirement account.

A representative told her, "You need that Form 42."

'They're going to keep all that money?'

Near the end of his life, Steven Leask was planning to retire. He calculated the value of his pension at close to a million dollars, enough to provide Libby with medical care and income the rest of her life if something happened to him.

Leask's papers include records of a 2000 audit of his NMSU retirement paperwork. Included on an audit checklist was a checkmark Libby believes was acknowledgment by Human Resources that it received Form 42.

However, staff at both NMSU and the ERB told Libby Leask there was no record of it and after combing through every file she could find, including her husband's personnel records, she did not locate a duplicate.

"20 years ago, people didn't make copies of all that stuff," she said. "You're working for NMSU. They take the originals, they send it all to ERB and you trust them ... I don't understand why they don't have copies."

Karin Foster of the Foster Legal Advisory Group in Albuquerque said failing to keep hard copies of documents, and beneficiary designations in particular, is a common pitfall.

"Even if it’s digitized, if you died and we don’t have your account number, we can’t get onto your account to check," Foster said. "If NMSU or whomever comes back and says there is no form, how would we know any different?"

Through her years in estate planning, Foster confirmed that lost records and mistakes are commonplace, which is why she recommends keeping paper records and reviewing them on a regular basis.

"In your portfolio you should have a copy of your last tax form, as well as beneficiary forms, update them every year make a habit of it," Foster said.

Because of the missing form, the ERB would only reimburse Leask's estate for the amount withheld from his paycheck over nearly 20 years — a fraction of what she expected.

"So they invested all these savings," Leask said, "and they're going to keep all that money?"

'It's the member's responsibility'

Jan Goodwin, the Educational Retirement Board's Executive Director, said, "It's the member's responsibility to make sure their beneficiary information is up to date and what they want."

With over 150,000 member accounts, including current and past employees and retirees of schools covered by the ERB, Goodwin said the organization relies on members to review their online accounts regularly and contact ERB about missing information or changes.

During a telephone interview with the Sun-News, Goodwin reviewed Steven Leask's account history, including paper records, and she said ERB had no record of receiving a completed Form 42.

NMSU, who declined to speak with the Sun-News for this story, reportedly told Libby Leask and ERB it had searched its archives for a copy but found none.

"If the wife is his beneficiary through his estate, she would be entitled to collecting all his contributions plus interest," Goodwin said, referring to ERB's payout to Steven Leask's estate.

Goodwin said ERB retains the original Form 42 once they receive it and make a digital copy. If a form is not completed properly, she said it is deemed invalid and returned to the school. She acknowledged that sometimes, for varying reasons, a replacement form never comes.

"The school may have a copy of it on file," Goodwin said. "We would honor that if the school could provide us with that copy. It's not usual that the form goes missing."

Yet Dwyer and Foster, the estate planning attorneys who talked with the Sun-News for this story, both indicated that forms do go missing from ERB and other institutions, and stressed the need not only to keep hard copies but to secure legal authorization for survivors to access personal devices and online accounts where important documentation is increasingly stored.

"In 2018, a new law went into effect in New Mexico related specifically to allowing people access to digital assets," Dwyer said. "That’s online email accounts, online storage, the cloud, online services that you pay for and have a license to use."

Libby said that when her husband died, he did not leave behind passwords to access his computer, much less any accounts that might provide clues about the missing form.

Fighting the system requires assets

Both attorneys recommended planning ahead with professional legal advice, as technology and laws pertaining to estates are changing rapidly.

"People don’t like to think about their death and catastrophic instances," Foster said, "but once you’re gone, you’re gone, and you can’t come back and say, 'What I meant was this.' You have to write it down ... so that when the time comes and family members are grieving, they have everything at their fingertips."

Leask said she consulted several lawyers about litigating the matter, only to be told she does not have a case.

Foster wondered whether recent case law might yet provide Leask with avenues of appeal, but acknowledged it would be expensive.

"There is precedent for courts assuming a living spouse should be the one to benefit from the assets, because he held her out as his spouse and the intention clearly was for her to get it," Foster said. "But that could be a long-term fight with the ERB."

Leask, already forced to make painful cuts to her living expenses, said she can't afford the legal battle.

Although she exercises daily, returning to her former profession as a home painter, climbing ladders and wielding paint rollers and brushes, will not be easy.

Diagnosed 15 years ago with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis, Leask said intermittent attacks come without warning.

"All of a sudden your legs just turn to limp noodles," she said. "You don't have any clue when it's going to happen. You can lose your eyesight, lose the use of your legs, your hands. A whole part of your body goes numb."

Worse still, among the expenses she has had to cut are the thrice-weekly Copaxone injections that reduce the frequency of her relapses.

After selling her home, Leask plans to move to California and live with her daughter.

https://www.lcsun-news.com/

When Elizabeth "Libby" Leask, 61, listed her Las Cruces home for sale early in February, she described it as a surrender.

"I don't have anything else to give up," she said. "I can't afford to fight anymore."

Since the sudden death of her husband in 2016, Libby Leask has been seeking her late husband's pension. As a multiple sclerosis patient, she was counting on the income to take care of her for the remainder of her life, as her late husband had planned.

Yet after 27 months consulting with attorneys and appealing for help from New Mexico State University, her husband's employer, and the New Mexico Educational Retirement Board, Leask is selling her home and preparing to move out of state to live with family.

Despite her medical condition, she will need to return to her former occupation — painting houses — in order to live.

What kept her from collecting her husband's pension was a single missing form: Form 42, the official form designating her as her husband's beneficiary.

'You need that Form 42'

Steven Leask was 66 when he died on Nov. 1, 2016. He had been a helicopter pilot in Korea, Vietnam and Alaska with the U.S. Army, earned a Master's degree and doctorate from NMSU, and since 1997 had worked for the university in the Educational Administration department.

In 2017, a memorial fund for Native American or military veteran students was established at the university in his name.

Libby vividly recalled coping with legal formalities in the midst of trauma over her husband's sudden death. At the FedEx store on University Avenue, her hands shook so much she needed an employee to help straighten her papers and fax them to the Educational Retirement Board.

Initially, she said an ERB representative told her the death certificate was all they needed, but subsequently they requested more documents, including parts of her husband's will.

"And then it was, 'We're not sure you're the beneficiary,'" Leask said. "I finally faxed them the whole will, everything, and then they ran out of things for me to fax."

It came down to the missing Form 42. Without it, Leask could not prove she was the designated beneficiary of her husband's pension, even though they had been lawfully married since 1985.

Josh Dwyer, an attorney at the Scott Hulse law firm in Las Cruces specializing in estate planning, said Leask's predicament is all too common.

"The legal framework for how these things work is very foreign to people until they're thrust in the middle of it," Dwyer said. "There are different rules for different types of assets, probate assets that are controlled by the will and non-probate assets, like bank accounts."

ERB suggested Leask go through probate and set up an estate. A few months and about $4,000 later, the estate was established, but then ERB attorneys told her Steven Leask's will did not prove she was the beneficiary of his retirement account.

A representative told her, "You need that Form 42."

'They're going to keep all that money?'

Near the end of his life, Steven Leask was planning to retire. He calculated the value of his pension at close to a million dollars, enough to provide Libby with medical care and income the rest of her life if something happened to him.

Leask's papers include records of a 2000 audit of his NMSU retirement paperwork. Included on an audit checklist was a checkmark Libby believes was acknowledgment by Human Resources that it received Form 42.

However, staff at both NMSU and the ERB told Libby Leask there was no record of it and after combing through every file she could find, including her husband's personnel records, she did not locate a duplicate.

"20 years ago, people didn't make copies of all that stuff," she said. "You're working for NMSU. They take the originals, they send it all to ERB and you trust them ... I don't understand why they don't have copies."

Karin Foster of the Foster Legal Advisory Group in Albuquerque said failing to keep hard copies of documents, and beneficiary designations in particular, is a common pitfall.

"Even if it’s digitized, if you died and we don’t have your account number, we can’t get onto your account to check," Foster said. "If NMSU or whomever comes back and says there is no form, how would we know any different?"

Through her years in estate planning, Foster confirmed that lost records and mistakes are commonplace, which is why she recommends keeping paper records and reviewing them on a regular basis.

"In your portfolio you should have a copy of your last tax form, as well as beneficiary forms, update them every year make a habit of it," Foster said.

Because of the missing form, the ERB would only reimburse Leask's estate for the amount withheld from his paycheck over nearly 20 years — a fraction of what she expected.

"So they invested all these savings," Leask said, "and they're going to keep all that money?"

'It's the member's responsibility'

Jan Goodwin, the Educational Retirement Board's Executive Director, said, "It's the member's responsibility to make sure their beneficiary information is up to date and what they want."

With over 150,000 member accounts, including current and past employees and retirees of schools covered by the ERB, Goodwin said the organization relies on members to review their online accounts regularly and contact ERB about missing information or changes.

During a telephone interview with the Sun-News, Goodwin reviewed Steven Leask's account history, including paper records, and she said ERB had no record of receiving a completed Form 42.

NMSU, who declined to speak with the Sun-News for this story, reportedly told Libby Leask and ERB it had searched its archives for a copy but found none.

"If the wife is his beneficiary through his estate, she would be entitled to collecting all his contributions plus interest," Goodwin said, referring to ERB's payout to Steven Leask's estate.

Goodwin said ERB retains the original Form 42 once they receive it and make a digital copy. If a form is not completed properly, she said it is deemed invalid and returned to the school. She acknowledged that sometimes, for varying reasons, a replacement form never comes.

"The school may have a copy of it on file," Goodwin said. "We would honor that if the school could provide us with that copy. It's not usual that the form goes missing."

Yet Dwyer and Foster, the estate planning attorneys who talked with the Sun-News for this story, both indicated that forms do go missing from ERB and other institutions, and stressed the need not only to keep hard copies but to secure legal authorization for survivors to access personal devices and online accounts where important documentation is increasingly stored.

"In 2018, a new law went into effect in New Mexico related specifically to allowing people access to digital assets," Dwyer said. "That’s online email accounts, online storage, the cloud, online services that you pay for and have a license to use."

Libby said that when her husband died, he did not leave behind passwords to access his computer, much less any accounts that might provide clues about the missing form.

Fighting the system requires assets

Both attorneys recommended planning ahead with professional legal advice, as technology and laws pertaining to estates are changing rapidly.

"People don’t like to think about their death and catastrophic instances," Foster said, "but once you’re gone, you’re gone, and you can’t come back and say, 'What I meant was this.' You have to write it down ... so that when the time comes and family members are grieving, they have everything at their fingertips."

Leask said she consulted several lawyers about litigating the matter, only to be told she does not have a case.

Foster wondered whether recent case law might yet provide Leask with avenues of appeal, but acknowledged it would be expensive.

"There is precedent for courts assuming a living spouse should be the one to benefit from the assets, because he held her out as his spouse and the intention clearly was for her to get it," Foster said. "But that could be a long-term fight with the ERB."

Leask, already forced to make painful cuts to her living expenses, said she can't afford the legal battle.

Although she exercises daily, returning to her former profession as a home painter, climbing ladders and wielding paint rollers and brushes, will not be easy.

Diagnosed 15 years ago with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis, Leask said intermittent attacks come without warning.

"All of a sudden your legs just turn to limp noodles," she said. "You don't have any clue when it's going to happen. You can lose your eyesight, lose the use of your legs, your hands. A whole part of your body goes numb."

Worse still, among the expenses she has had to cut are the thrice-weekly Copaxone injections that reduce the frequency of her relapses.

After selling her home, Leask plans to move to California and live with her daughter.

Organizer and beneficiary

Laura Grant

Organizer

Las Cruces, NM

Elizabeth Leask

Beneficiary