"I Am The Hope And The Dream" Part. 2

Donation protected

My name is Remy Styrk and I'm the director and editor of the documentary I Am The Hope And The Dream. I'm an award-winning trans (he/him) black queer filmmaker and musician.

In May of 2022, I and a team of powerful black community leaders in Whatcom County, Washington made a film called "I Am The Hope And The Dream". It was a public health short documentary about Juneteenth and how the community members celebrate/their relationship with the holiday. The film was shown in several schools throughout Whatcom County, even making its way into classrooms across the U.S. This was the beginning of celebrating and uplifting black voices with light. Part two will showcase the light and joy of our stories outside of our skin color - our light as humans. Help me uplift black voices. Donate today!

Donations will go towards paying the crew (lighting, sound, 2nd camera operator, set PA, BTS photographer), equipment, transportation, locations, etc.

Watch part one here → https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gG3n9mMKRB8

FULL STORY ↓ ↓ ↓

In March of 2022, my cousin, Anya Milton, reached out to me about working on a public health film about Juneteenth for Connect Ferndale, a program run through Ferndale Community Services. The project was the perfect opportunity to uplift and celebrate black voices at an intimate grassroots level; the beginning of representing black lived experiences. When Anya reached out, I had just moved to New Jersey from Kansas City and was going through a stage of being untethered in many aspects of my life. It was the first time moving out of my childhood home and into my young adult continuance. At a time when I really began to explore my voice, character, and influence, the Juneteenth project was a gift both laid at my feet to care for and one that invited me in. I quickly met the rest of the team I’d be working with, followed by many creative planning meetings. May came around and I flew out to Bellingham to begin filming.

Once I got on the ground, felt the energy in the room, and began bonding face-to-face with the team, a monumental shift happened. Calling our group a team no longer seemed fitting, only “family” could describe us. There was a level of trust that was almost heartbreaking. To sit down in an interview with the community leaders and all we had to do to genuinely connect, to wordlessly acknowledge and respect our shared trauma, was to lock eyes was transcendental. In that moment of heaviness - collective heaviness - also came a rebirth of freedom. It opened the door to discussing how internal freedom affects external freedom rather than the other way around. For me, it was pivotal to be seen, loved, and valued in all shades of my story. This was unfettered community right before my eyes.

I remember the exact minute my being broke during filming. I was interviewing Blaine Police Chief Donnell “Tank” Tanksley and he was talking about living in Ferguson, Missouri so close to the fatal shooting of Michael Brown. The ineffable turning point of hearing the story, face-to-face one-on-one, of someone so close to a traumatic event, engulfed me. To hear the fatigue of racial battle with the foundation of gratitude to be alive in his voice, to watch his smile waver, to see a human embrace their gift of life without limits proved to me that our people, black people, are born of resilience and humility. That is our foundation. You can strip everything away from us and we will still be resilient.

When we wrapped filming, I remember waking up that next morning in the hotel room, looking in the mirror, and seeing someone I didn’t recognize. There were fragments of characteristics I tried to grasp, but the harder I reached the further they slipped into this purgatory. I closed my eyes and I could see my younger self there waiting, pleading for guidance and for a home. I could hear him wishing for a voice. He was hurt, misplaced, and tired, but he was resilient. He is resilient. This connection with him, little did I know, would change my life forever. I am adopted into a white family and my dad arguably doesn’t see color. Growing up, I could only advocate for myself as much as my age allowed. After connecting with my younger self, I expressed to my dad how I felt as a kid and how I feel like I missed out on learning about my culture, my people, and how I never felt seen for who I am as a black person in America. He did not take it well. There was a lot of gaslighting and attempts to justify his lack of knowledge. While he did an incredible job raising me as his son, as his black son I never felt supported. It created a massive amount of tension between us and pushed me into a really low place. I was, and still am, extremely grateful to have Anya through this. In a time when I needed a parent, a guiding light, a safe space, she stepped up. She offered that I live with her and her family while I get my feet back under me. It was the best possible decision I’ve made. I am finding real community here and absorbing the love I’ve always wanted. I moved to Ferndale in October of 2022.

Since I’ve been here and had time to reflect more on the original Juneteenth film, the biggest realization I’ve had is: Sometimes it takes seeing someone who looks like you doing something you want to do to even imagine it possible. Thinking about the word “representation” in the context of black people in the eyes of white people, its true definition creeps further and further away. I can’t define representation, but I know it when I see it. To be represented is to relate, but all we are representing is disconnect. We are all relating to disconnect and becoming increasingly uncomfortable. Then we reach a point where we are scared to push to be represented, creating a tape loop. Black people are more often portrayed and represented with violence, police brutality, drugs, street crime, and anti-family language. Safe spaces and opportunities for black voices to be heard are twisted into healing moments for white people (e.g. films about slavery, trauma-forward black experiences, etc.). We are never seen in the context of light. We are never seen as humans outside of our collective trauma.

I am going to change that. I am going to use my voice to help my people be heard. We are the light. We are the blueprint of greatness and that deserves to be shown. Our trauma does not define us, though it has shaped us. Juneteenth part 2 will showcase the light. You will see and hear how Juneteenth directly affected these personal stories - what it truly means to be the hope and the dream of the slave.

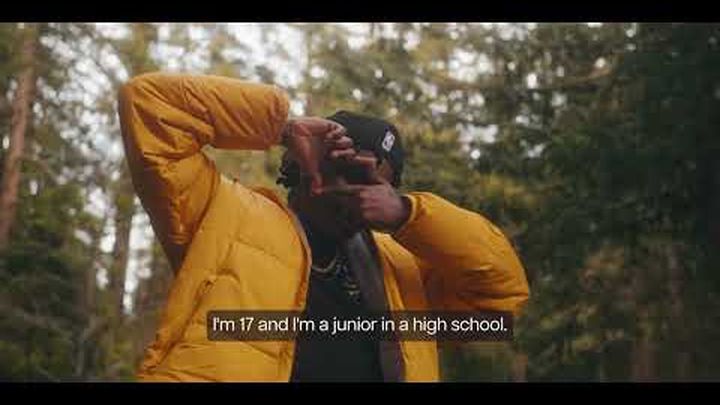

Now, there is another person who really caught my attention from our filming family and someone who is very close to my heart. That person is Isaac Gammons-Reese. He is a Whatcom County high school student in whom I see parts of younger Remy in. He is the future of today. I would like to pass it off to him in a short video of how the original film impacted him and why part 2 is important not only to him but to the community of Whatcom county.

(Video at top of page is starring Isaac Gammons-Reese.)

Organizer

Remy Styrk

Organizer

Ferndale, WA