A Voice For Maya Genocide Survivors

Donation protected

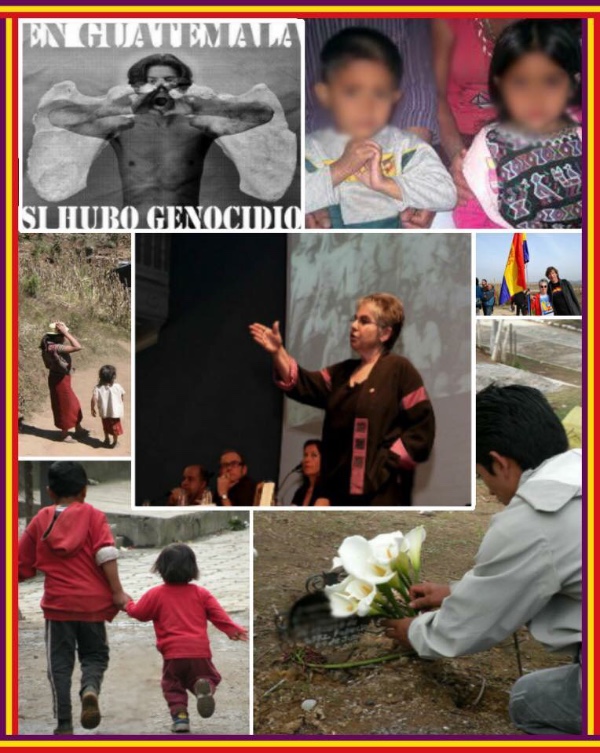

UNCONCLUDED WAR: Help Laurie Levinger Return to Guatemala to Publish More Testimonies of the Mayan Genocide

by Adam Cornford and Sandra Mendez Rosenbaum

A couple of years after progressive hearing loss forced her early retirement as a therapist, Laurie Levinger volunteered in 2004 to teach English in Guatemala, Central America. In conversation with local teachers and students, she soon began to uncover a horror story. During the 1980s, while US media attention was focused on neighboring Nicaragua and El Salvador and the Reagan administration was helping right-wing terrorists there "fight communism" with bombings, torture, and assassinations, the indigenous Maya people of Guatemala were being subjected to a genocide.

Repression and Civil War in Guatemala

The Guatemalan military had in effect ruled the country on behalf of the criollos--the light-skinned descendants of Spanish colonials--since its independence from Spain in 1821. The only exception was the period 1944-1954, when two democratically elected civilian governments attempted modest reform. The second of these governments was overthrown in a military coup organized by the CIA. In the 1960s, after countless decades of oppression, students, workers, and peasant farmers formed an armed resistance coalition that began a guerrilla war against the government. This first wave of insurgency was crushed. During the 1970s a succession of military dictators subjected the middle and working classes of the country to unrelenting and savage repression, including the "disappearing" of journalists, human rights activists, labor leaders, and progressive clergy.

The new guerrilla groups that emerged as a desperate response found strong support among the indigenous people in the countryside. Mayans made up the great majority of the insurgent fighters. Between 1978 and 1989, with the training and material support of the US, successive military-backed regimes, most notoriously that of General Efrain Rios Montt, adopted a policy of literal "scorched earth" terror against the rural Mayans. Any village suspected of harboring guerrillas or even of sympathizing with the insurgency was subjected to mass slaughter. In many cases not even children were spared. The homes and lands of the villagers were then incinerated. Torture, rape, and atrocity were widespread. Tens of thousands who survived these massacres fled into the remote highlands or across the border into Mexico. But despite all this, the insurgency continued, neither victorious nor defeated. A peace accord between the insurgents and the government was finally reached in 1996.

A Legacy of Atrocity and Courage

According to the final report of Guatemalan Truth Commission, which had been founded in 1994: "During the internal armed confrontation there were 626 massacres, 1.5 million people were displaced, 150,000 became refugees, and more than 200,000 were dead or disappeared. In the Ixil region alone between 70% and 90% of the villages were burned to the ground. [These were]… acts committed with the intent to destroy in whole or in part numerous groups of Mayans. […]State forces and paramilitary groups were responsible for 93% of the violations […] 83% of the victims were Mayans." When this report was issued in 1998, its sponsor, Bishop Juan Gerardi, was murdered two days later. This is an indication of the quality of the "peace" that had been achieved and that persists to this day. There has been some limited reform: Maya people can attend university and enter the professions, though they still face informal discrimination and the vast majority remain desperately poor. The government, meanwhile, has declared that there was no genocide and that legally, no such thing could possibly have happened.

Becoming aware of all this in her conversations, Laurie decided to start collecting and writing down testimonies from survivors of the Maya genocide. Between 2004 and 2008, she returned to Guatemala many times to gather more testimonies. The stories she collected and wove together with her personal experiences and observations in her first book What War? are heartbreaking, startling, inspiring, and deeply moving. Anyone who wants to understand what civil war and military dictatorship do to individual human beings should read the book. It has been translated into Spanish as ?Cual Guerra?

Here is what Fernando, a Maya survivor whom she interviewed and came to know well, said about the book: "After reading ?Cual Guerra?... my first feeling is the importance of keeping the memory and (the need) to rescue the memory. Because with the civil war, we lost, we lost our process, we lost our life. We lost our opportunity to talk and to say what is going on in our life, what we were feeling because of the civil war, because of oppression, because of repression. […] So with this opportunity to talk and to remember…that we were living in this time, you know, and we have to remember what we felt, we cannot continue in life forgetting or losing this part of our memory. So, I say it is important to keep the memory. Not just for the next generation, but for all the world, for us, for our dignity, for our existence."

But Laurie collected many more testimonies than could be contained in that first book. From them she has woven a second, titled Guerra inconclusa: La voz de sobrevivientes--"Unconcluded War: The Voice of Survivors." Now she wants to return to Guatemala to launch the book there. She needs money for translation, copyediting, and publication and publicity costs. We're helping her effort with this new campaign on GoFundMe.

Organizer and beneficiary

Sandra Mendez Rosenbaum

Organizer

Thermal, CA

Laurie Levinger

Beneficiary