Reverend William J. Ancient Headstone Fund

Donation protected

During the early morning hours of April 1, 1873, the White Star Line steamship Atlantic struck a rock on the western side of Meagher’s Island, Nova Scotia. Several hundred panic-stricken passengers soon piled on deck. Through the heroic effort of some of the ship’s crewmembers, three lines were stretched to a rock only 70 feet wide as a means to escape the sinking steamer.

Some 200 or so passengers made the perilous 40-yard trip over the ropes to the rock. Chief Officer John W. Firth could not swim and sought sanctuary in the mizzen rigging to wait for help as the ship began to break apart. By daylight, Firth counted 32 others with him. Three small rescue boats arrived but couldn’t get to Firth and the others for fear of wrecking themselves. Third Officer Cornelius L. Brady, instrumental in saving many lives on the Atlantic, tried to gather a crew to go out again to rescue Firth and the others, but nobody volunteered. Even the most experienced fishermen thought it was a suicidal task. Who would risk their lives to save these remaining passengers?

By noon, Firth and a 17- or 18-year-old youth were the only living souls still on the wrecked steamer. “I could see the people on shore and in the boats and could hail them,” Firth later recalled, “but they were unable to reach us.” Firth had secured Rosa Bateman, who had climbed the rigging with them. She had grown weak from hypothermia and had expired soon after, leaving just him and the youth as the lone survivors.

The shipwreck had taken place only a mile from Lower Prospect, a small fishing village located about 30 miles southwest of Halifax. Once informed of the disaster that morning, the Reverend William Ancient, an Anglican priest from nearby Terence Bay and retired sailor of the Royal Navy, coordinated the efforts to help the survivors that had safely made it to shore. He went to the local magistrate, Edmund Ryan, once he caught wind that three people were still clinging to the ship’s rigging.

“The water is smooth enough,” he told Ryan. “You can get alongside in a boat.” Ryan agreed that a boat could get close to the wreck, but not close enough to conduct the rescue. “Give me a boat and some men,” Ancient demanded. “[P]ut me on board and I will get them.” Four volunteers joined Ancient in a boat and headed to the wreck. Once it got close enough to the wreckage, the men refused to allow Ancient to board it for fear that he would meet certain death. “John, if I am doomed, I won’t hold you responsible,” Ancient assured 46-year-old John Hooper Slaunwhite. “Put me on board.”

The youth interrupted the debate when he plunged into the water. Luckily, he was close enough for the boat to reach him. The boat dropped him off into the waiting arms of those people watching from the shore and then went back out for the last survivor.

The boat pulled up to the bow of the shipwreck around 2:00 p.m., a spot which offered the greatest protection to its passengers. Firth had been in the rigging for 10 hours and was losing strength.

Ancient pulled himself up onto the hull. Once aboard the wreckage, he climbed the mainmast rigging, where he cut two long lengths of rope and made his way to a lifeboat davit. He then secured the rope to the davit and started the treacherous walk back to the mizzenmast, attaching the rope to other davits as he went. The base of the mizzenmast was underwater, so he lashed himself on and hurled the second rope up to Firth, telling him to tie it around his waist.

“Now put your confidence in man and the Lord and move when I tell you,” he yelled to the chief officer. When Firth started to climb down the shrouds, his legs gave out and he fell into the water, but Ancient held fast to the line. Firth cried out that he had broken his shins. “Never mind your shins, man,” Ancient called out. “It is your life that we are after.” Ancient then methodically led the exhausted chief officer back along the rail to where the rescue boat was waiting. “I was then so exhausted and benumbed that I was hardly able to do anything for myself,” Firth afterward recalled, “and but for the clergymen’s gallant conduct I must have perished soon.” Firth would never forget Ancient’s noble conduct as long as he lived.

It was a feat of incredible courage, seamanship and endurance and Ancient was lauded around the world. He received medals from the Royal Lifesaving Society and the Liverpool Shipwreck and Humane Society, a commendation from the Humane Society of Massachusetts and gold watches from the City of Chicago and the Government of Canada, along with numerous cash rewards.

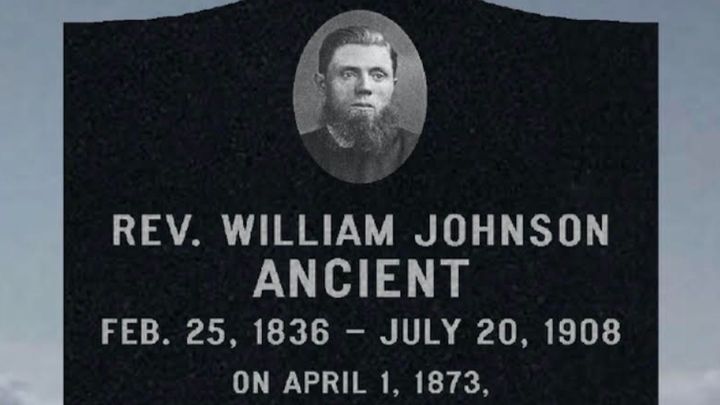

William Johnson Ancient died on July 20, 1908, at his residence in Halifax at the age of 72. He was buried at Saint John’s Cemetery. “[O]n ship board, in parish life and in the Synod office,” Bishop Clarendon Lamb Worrell stated of Ancient, “his sense of duty was plainly marked and whatever he did was done to the best of his ability and in singleness of purpose.” Sadly, Reverend William J. Ancient’s grave is currently unmarked. With the consent of his descendants, I contacted Heritage Memorials and commissioned a headstone to be placed at his grave (There will NOT be a white line running across the middle of the headstone as you see in the photo. I was unable to upload a single photo here, so I had to upload two separate photos.) The total expense will come to $3,115 — this fee includes the lettering, tax, delivery, etching, installation, and stay straight guarantee. This is a small fee for a model Christian who risked his life to save another.

John 15:13: “Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends.”

Some 200 or so passengers made the perilous 40-yard trip over the ropes to the rock. Chief Officer John W. Firth could not swim and sought sanctuary in the mizzen rigging to wait for help as the ship began to break apart. By daylight, Firth counted 32 others with him. Three small rescue boats arrived but couldn’t get to Firth and the others for fear of wrecking themselves. Third Officer Cornelius L. Brady, instrumental in saving many lives on the Atlantic, tried to gather a crew to go out again to rescue Firth and the others, but nobody volunteered. Even the most experienced fishermen thought it was a suicidal task. Who would risk their lives to save these remaining passengers?

By noon, Firth and a 17- or 18-year-old youth were the only living souls still on the wrecked steamer. “I could see the people on shore and in the boats and could hail them,” Firth later recalled, “but they were unable to reach us.” Firth had secured Rosa Bateman, who had climbed the rigging with them. She had grown weak from hypothermia and had expired soon after, leaving just him and the youth as the lone survivors.

The shipwreck had taken place only a mile from Lower Prospect, a small fishing village located about 30 miles southwest of Halifax. Once informed of the disaster that morning, the Reverend William Ancient, an Anglican priest from nearby Terence Bay and retired sailor of the Royal Navy, coordinated the efforts to help the survivors that had safely made it to shore. He went to the local magistrate, Edmund Ryan, once he caught wind that three people were still clinging to the ship’s rigging.

“The water is smooth enough,” he told Ryan. “You can get alongside in a boat.” Ryan agreed that a boat could get close to the wreck, but not close enough to conduct the rescue. “Give me a boat and some men,” Ancient demanded. “[P]ut me on board and I will get them.” Four volunteers joined Ancient in a boat and headed to the wreck. Once it got close enough to the wreckage, the men refused to allow Ancient to board it for fear that he would meet certain death. “John, if I am doomed, I won’t hold you responsible,” Ancient assured 46-year-old John Hooper Slaunwhite. “Put me on board.”

The youth interrupted the debate when he plunged into the water. Luckily, he was close enough for the boat to reach him. The boat dropped him off into the waiting arms of those people watching from the shore and then went back out for the last survivor.

The boat pulled up to the bow of the shipwreck around 2:00 p.m., a spot which offered the greatest protection to its passengers. Firth had been in the rigging for 10 hours and was losing strength.

Ancient pulled himself up onto the hull. Once aboard the wreckage, he climbed the mainmast rigging, where he cut two long lengths of rope and made his way to a lifeboat davit. He then secured the rope to the davit and started the treacherous walk back to the mizzenmast, attaching the rope to other davits as he went. The base of the mizzenmast was underwater, so he lashed himself on and hurled the second rope up to Firth, telling him to tie it around his waist.

“Now put your confidence in man and the Lord and move when I tell you,” he yelled to the chief officer. When Firth started to climb down the shrouds, his legs gave out and he fell into the water, but Ancient held fast to the line. Firth cried out that he had broken his shins. “Never mind your shins, man,” Ancient called out. “It is your life that we are after.” Ancient then methodically led the exhausted chief officer back along the rail to where the rescue boat was waiting. “I was then so exhausted and benumbed that I was hardly able to do anything for myself,” Firth afterward recalled, “and but for the clergymen’s gallant conduct I must have perished soon.” Firth would never forget Ancient’s noble conduct as long as he lived.

It was a feat of incredible courage, seamanship and endurance and Ancient was lauded around the world. He received medals from the Royal Lifesaving Society and the Liverpool Shipwreck and Humane Society, a commendation from the Humane Society of Massachusetts and gold watches from the City of Chicago and the Government of Canada, along with numerous cash rewards.

William Johnson Ancient died on July 20, 1908, at his residence in Halifax at the age of 72. He was buried at Saint John’s Cemetery. “[O]n ship board, in parish life and in the Synod office,” Bishop Clarendon Lamb Worrell stated of Ancient, “his sense of duty was plainly marked and whatever he did was done to the best of his ability and in singleness of purpose.” Sadly, Reverend William J. Ancient’s grave is currently unmarked. With the consent of his descendants, I contacted Heritage Memorials and commissioned a headstone to be placed at his grave (There will NOT be a white line running across the middle of the headstone as you see in the photo. I was unable to upload a single photo here, so I had to upload two separate photos.) The total expense will come to $3,115 — this fee includes the lettering, tax, delivery, etching, installation, and stay straight guarantee. This is a small fee for a model Christian who risked his life to save another.

John 15:13: “Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends.”

Organizer

Frank Jastrzembski

Organizer

Hartford, WI