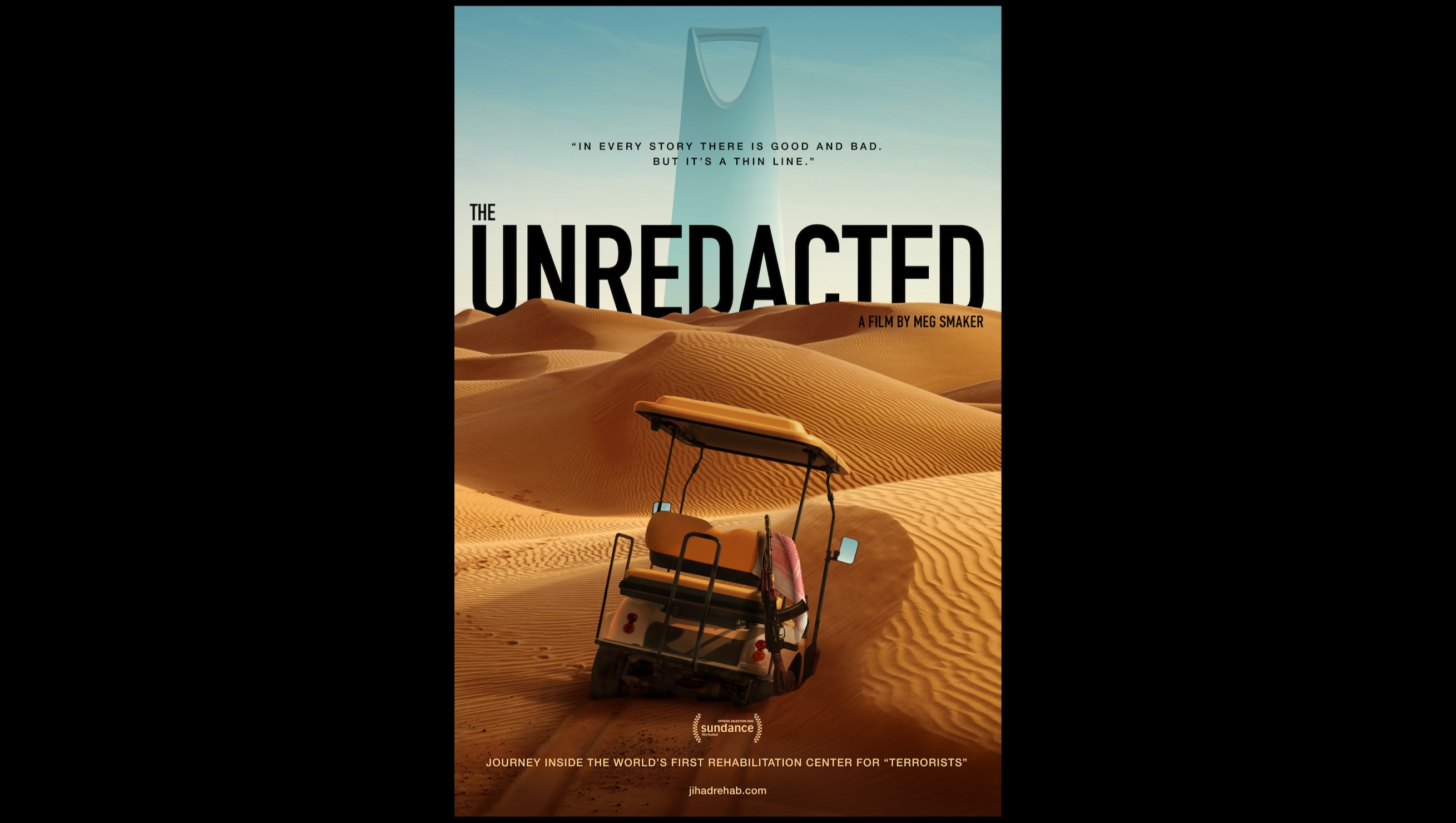

The UnRedacted (Jihad Rehab)

Donation protected

Hi, my name is Meg Smaker and I am the director of the documentary The UnRedacted (Jihad Rehab). The film follows a group of men trained by al-Qaeda who are transferred from Guantanamo and sent to the world’s first rehabilitation center for “terrorists” located in Saudi Arabia. The film premiered at Sundance this year and received rave reviews from film critics (Reviews: www.jihadrehab.com ). Unfortunately, the film became the target of a campaign that eventually got the movie essentially blacklisted. See this New York Times article for the full story... (https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/25/us/sundance-jihad-rehab-meg-smaker.html)

At this point in time, the only way to get this movie to the public is to try and distribute the film myself - which is not cheap. (Trailer, Posters, Renting Theaters for screenings, etc). I don't come from money, as the daughter of a firefighter, and a former firefighter myself, the kind of resources needed to put this kind of thing together are way outside my tax bracket. But, as we used to say in the fire service "improvise, adapt, and overcome".

Please donate and help me bring this film to the world, and possibly to a theater near you!

We are raising money to help pay for...

1) Making a trailer for the film (Update- Trailer DONE :) - thank you so much for your donations that made this possible- see Official Trailer Above)

2) Getting posters made to promote the film (Update- Poster DONE!- Created by a Sam Harris Listener named Zach!- see below)

3) Renting theaters in different cities across the United States to play the film for audiences to be able to see the film and make up their own minds.

4) Legal Fees (Cuz, unfortunately, you always need lawyers in this country)

Here is my director's statement about why I made this film...

Before I was a filmmaker, I was a firefighter. I loved it, and I thought I’d always be one.

Then 9/11 happened. When the towers came down, my understanding of the world came crumbling down with them. The world presented to me by popular media – a simplistic world of good and evil, us vs. them – seemed to answer none of the questions burning inside of me, raised by the events of that day and its aftermath.

My father used to say, there are only three types of people in the world:

• Those that when you hit them, they hit you right back

• Those that when you hit them, they run away

• And… those that when you hit them, they ask, “Why did you hit me?”

I’ve always been in that third camp.

So about six months after 9/11, I traveled to Afghanistan to find those answers for myself. And was immediately humbled by my own ignorance of the world.

As America carried out bombing raids and ground operations with Allied forces in Afghanistan, I was staying in a small village in the northern province of Balkh. A local family had taken me into their home, fed me, clothed me, and treated me as one of their own. Though they did not speak any English, we were able to communicate through my rudimentary grasp of Dari and my (only slightly better) abilities at charades. One day, the grandfather of the house and I were walking through the local market when another man began beating his fist in the air and shouting at me. Though I had no idea what he was saying, the anger and disgust on his face made his meaning clear. Almost immediately my surrogate grandfather ran up to the man, grabbed him by the collar, and started shaking him and shouting back. This exchange lasted only a few seconds, but resulted in the man saying “Sorry,” in Dari and then, “Welcome to Afghanistan,” to me in English.

Weren’t these the people who were supposed to hate us “because of our freedoms?” Why would this elderly man, this stranger, defend me against his neighbor whom he’d probably known for years? Me – an American, whose country was at that very moment bombing and occupying their land. But here was a family who despite not knowing me, welcomed me into their home and treated me with hospitality, kindness, and grace. My preconceived notions of this country and its people were so wrong it shook me to my core, bringing my whole worldview into question.

I was 21 years old, and it was the first time I was humbled by my own ignorance of the world, but it definitely would not be the last.

My time in Afghanistan taught me that my understanding of the world was extremely limited, but also that the way to broaden it was to spend time with people different from me and to try to see the world as they saw it. This was the driving force behind my decision to move to Yemen and to study Arabic and Islam.

Learning Arabic helped me get a job as the head firefighting instructor at a fire academy in Sana’a, the capital of Yemen. While running the cadets through some fire drills, I overheard a conversation between three of the men. There had been a terrorist attack in Saudi Arabia. The perpetrators who had been caught were a group of al Qaeda members, half of them Yemeni, the other half Saudi. According to the cadets, the Yemenis had been executed but the Saudis had been sent to something they referred to as “Jihad Rehab.”

It was the first time I’d heard about the center. Saudi Arabia was not known for being progressive. Yet here they were running a rehabilitation center for terrorists?

That story always stuck with me, and years later when I finally became a filmmaker, I knew it was something I had to explore.

Partly because of what happened on 9/11, I wanted to know more about the people who had killed so many of my fellow firefighters. But I also wanted to know more because Yemen had become my second home. I had people there I considered family, and still do to this day. While living there I saw the devastation America caused in this region in the name of “fighting evil” and the “War on Terror.” But who were these “evil” people? Throughout all those years living in Yemen and the Middle East, I had never met one. I was torn. As a firefighter I saw America as a victim, but living in Yemen, I also saw the U.S. as a perpetrator of violence.

I had one foot in each world. But I still didn’t fully understand.

As children we are told stories about good and evil: the good witch and the bad witch. The roles are very clear. The good witch is good because… she was just born that way. Same for the bad witch. It’s a clean and comforting view of the world. Though we’re told these stories as children, I think many of us struggle to ever evolve past this worldview. We have allies and enemies. We are good and they are bad. And that is where the understanding stops.

I know because I also held this view – far past childhood.

I held it until I was kidnapped.

My kidnapping is also a big part of why I made this film. And where my obsession with understanding the “other” probably stems from.

I was kidnapped in Colombia for 10 days in 2003. During my captivity, my kidnappers disemboweled and decapitated seven people in front of their families. Afterward, the captors pillaged and burned the villages of those victims to the ground. It was the very definition of evil.

But it wasn’t the killings or the beatings or the destruction of the villages that really changed me. It was what happened after.

Being kidnapped isn’t like it is in the movies. There are no big explosions or men dressed in all black performing long diatribes. With no access to Internet or forms of distraction, being kidnapped can actually be kind of boring. Most of the time, you’re just sitting around and talking: talking with fellow captives, and eventually, talking to your captors. With nothing to do, you have time to talk about the most random things, and to pass the time our conversations would go on for hours. As we talked I began to feel more and more unnerved. Not from the deeds they had just done, but from how normal they all were. Far from the blood-thirsty psychopaths I’d imagined, these were just your run-of-the-mill young men and women. They talked about high school crushes, their favorite football teams, and eventually, we talked about why they joined this rebel group of mercenaries.

One of the young women recounted her story. Her parents had been killed by the FARC and in her mind the only logical thing to do was to join the rival group, the AUC. It was the AUC’s job to hunt down the FARC and any FARC sympathizers. When they found them, they were to “send a message” by disemboweling and then cutting off their heads in front of their family to dissuade anyone else from helping the FARC.

This was it. She was the monster I read about as a child. Doing evil things to innocent people. But she was no monster at all – just a 20-year-old girl. Her trajectory from teenage girl to executioner had nothing to do with being born evil. It wasn’t about good and evil at all, it was simply about time and circumstance.

The lens through which I had so confidently viewed the world was once again thrown into question.

This was part of the catalyst that pushed me on this lifelong journey of trying to understand the world’s “evildoers”: Pirates in Somalia, warlords in Afghanistan, and terrorists in Saudi Arabia. Somehow, it’s like a safety blanket. Like if I can understand a thing, then it’s no longer so scary to me.

There’s this quote I read years ago in a Dostoevsky novel: “Nothing is easier than to denounce the evildoer; nothing is more difficult than to understand him.”

I suppose this film I made is trying to do that difficult thing. Because I never got into documentary filmmaking to save the world, I just wanted to better understand it.

Organizer

Meg Smaker

Organizer

Oakland, CA